The video addresses the philosophical debate concerning the existence of a unifying principle or metanarrative in reality, contrasting postmodern perspectives with classical views. The speaker examines the postmodern claim that there is no overarching unity, highlighting the implications for perception and understanding of reality. Through examples like French impressionist art and philosophical arguments by figures such as Foucault, Derrida, and Hume, the complexities of reconciling multiplicity with unity are discussed.

This discussion is further extended by linking historical philosophical thoughts from figures like Heraclitus and David Hume to modern scientific perspectives, such as quantum mechanics. The concept of induction, predictability, and the inherent uncertainty within nature according to quantum theory are debated, with references to notable figures like Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein. This forms a bridge between classical objective reality and quantum possibilities, challenging deterministic views.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. transcendent [trænˈsɛndənt] - (adjective) - Surpassing usual limits; beyond ordinary experience or understanding. - Synonyms: (superior, supreme, surpassing)

This is another one of the weaknesses of the postmodern claim that there's no transcendent unity.

2. metanarrative [ˈmɛtəˌnærətɪv] - (noun) - An overarching story or narrative that gives meaning to smaller stories or concepts within a culture. - Synonyms: (oversight story, grand narrative, macro-narrative)

...no metanarrative, which is another. Which is a restatement of the idea of the collapse of the highest...

3. induction [ɪnˈdʌkʃən] - (noun) - The inference of general laws from particular instances. - Synonyms: (inference, reasoning, conjecture)

And that's his scandal of induction.

4. irrevocably [ɪˈrɛvəkəblɪ] - (adverb) - In a way that cannot be changed, reversed, or recovered. - Synonyms: (unchangeably, permanently, unalterably)

Like, seriously, not fundamentally predictable. irrevocably.

5. inference [ˈɪnfərəns] - (noun) - A conclusion reached based on evidence and reasoning. - Synonyms: (deduction, conclusion, reasoning)

Yeah. And the whole thing is infinite inference, essentially.

6. deterministic [dɪˌtɜːrmɪˈnɪstɪk] - (adjective) - Relating to the belief that all events are predetermined and therefore inevitable. - Synonyms: (predestined, preordained, inevitable)

And Einstein wonderfully says, if this is true, then it's the end of physics, because to him, physics means it's deterministic.

7. constituent [kənˈstɪtʃuənt] - (adjective) - Being a part of a whole. - Synonyms: (component, integral, essential)

They're separate in time, they're separate in place. The constituent elements are completely different.

8. manifestation [ˌmænɪfɛˈsteɪʃən] - (noun) - An event, action, or object that clearly shows or embodies something abstract or theoretical. - Synonyms: (demonstration, display, expression)

And they might say, well, there's a limit to the manifestation of that unity.

9. periodic [ˌpɪəriˈɒdɪk] - (adjective) - Occurring at regular intervals. - Synonyms: (cyclical, recurrent, regular)

And you see echoes of that in Genesis, because God is also periodically characterized as the victor of the battle over Leviathan, for example, which looks like an analog of Tiamat

10. ought from an is [ɔːt frɒm æn ɪz] - (phrase) - The philosophical idea that one cannot derive prescriptive statements (what ought to be) from descriptive statements (what is). - Synonyms: (moral reasoning, prescriptive-dilemma, ethical theory)

You can't get an ought from an is.

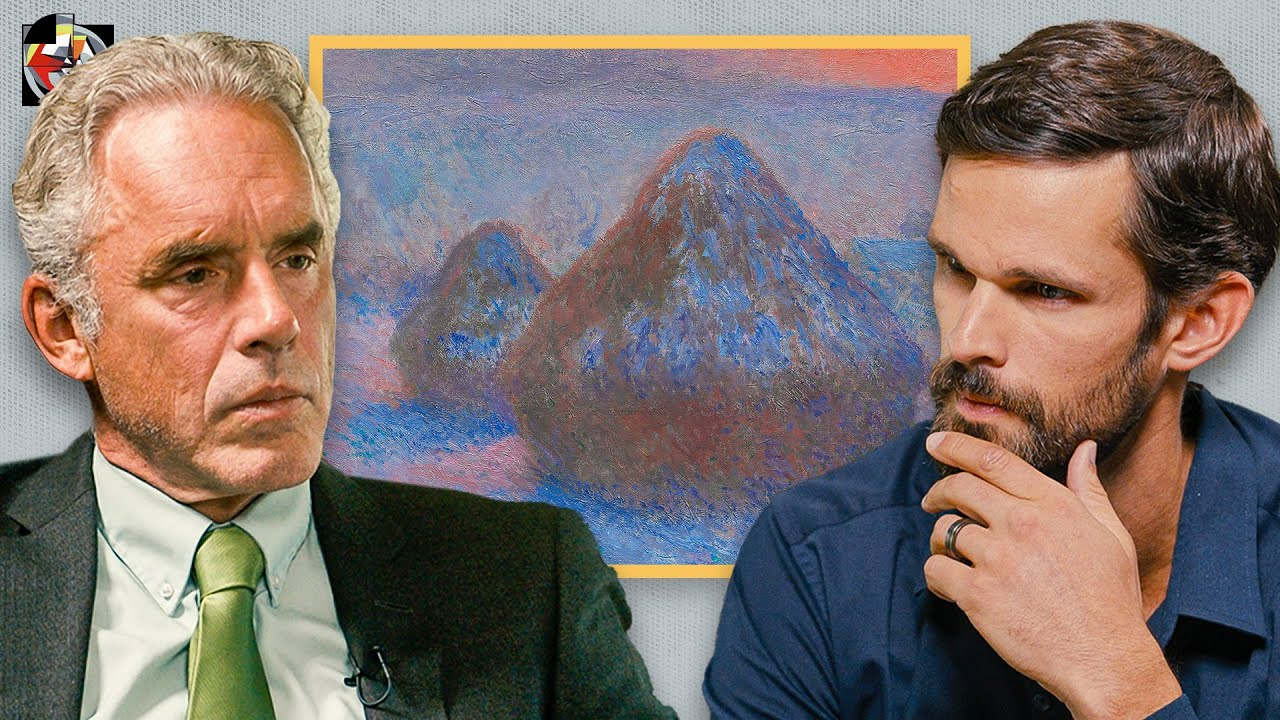

What Monet's Haystack Paintings Demonstrate About Reality - Spencer Klavan

This is another one of the weaknesses of the postmodern claim that there's no transcendent unity, no metanarrative, which is another. Which is a restatement of the idea of the collapse of the highest, the collapse of the unifying principle, the collapse of God, the death of God. See, one of the real problems with that hypothesis is that it's boundless. So there's no. There's no inevitable higher order unity. Okay, at what level of analysis are you speaking? Because if I'm going to perceive this as a glass, then all of the multitude of things that that glass is, that the different molecular positions that the liquid inside it might take, all the different ways that a glass could make itself manifest, all that has to be subsumed into a unity.

That is the glass. Yes. Now there's a. I think it's Manet, but it might be Monet, I don't remember, French impressionist who went out and painted haystacks. Yes, a whole series of them under different series, different conditions of illumination. Right. And the haystack is the same. But of course it's not because the. The colors that constitute the haystack shift dramatically. And that's what he was investigating. Yeah, it's so interesting because two paintings of the same haystack, really, at the micro level, bear nothing in common. Right? There's nothing in common. They're separate in time, they're separate in place. The constituent elements are completely different.

But there's an emergent reality, which is the haystack, that unifies all those variants in form and makes the perception possible. Now, the postmodern claim is that there's no overarching meta narrative. It's like if there's no overarching metanarrative, you can't even. You can never perceive a unity. And they might say, well, there's a limit to the manifestation of that unity. Right? There's no ultimate unity. It's like, oh, yeah, fine, draw the line. Tell me exactly where the unity stops. And it's worse than that, because let's assume that they're right, that there is no uniting metanarrative, so no single proper way of looking at the world. You can understand that something might be said about that?

Well, then, does that mean that the ultimate reality is disunified, that there are various forms of fundamental truth? And if reality itself can't be unified because it's not unified in its essence, then are we destined to conflict between our own motivations, even? And how do you and I agree on anything if it doesn't point towards a unity that's actually apprehensible and in some way implicit in the world. This is why. This is a huge, huge problem. This is why I was so struck by what you were saying about Foucault and Derrida. I think we can kind of put Lacan in here too, because it mirrors something that happened to me at the end of writing this book.

You always come to a few surprises if you're onto something in a good book. And to me, the biggest surprise was that I understood the postmodernists in a completely new way. And I understood them actually as part of a tradition that probably goes back to Heraclitus. Speaking of Greek Greeks. Right. Yeah. Right. The river. Yes. But also runs through people like David Hume and even Bishop Barclay who are reacting to this objectivist idea. Yeah. Hume's problem is you cannot compute a pathway forward merely by understanding the terrain. Right. You can't get an ought from an is. Yeah. And the whole thing is infinite inference, essentially.

And he's saying that the only thing that we have in front of us is the fact that the sun has always risen in our experience and all recorded human experience. And it's only on that that we're able to base the idea that the sun's going to rise tomorrow, which shatters this idea of something that remains consistent from day to day. And that's his scandal of induction. Yes. Right. That's the problem the chicken has with the farmer. Right, Exactly. The farmer is the chicken's best friend. Every day the farmer brings food until it's Thanksgiving, in which case the faith the chicken has in the structure of the world as a consequence of induction turns out to be painfully wrong. Yeah.

And the problem is we never know. And Hume was pointing this to some degree. We never know when the rug is going to be pulled out from underneath us. Yes. Or at what level. You could even take the sun itself, I've thought. Because you think, well, there's nothing more consistent than the sun. It's like. Well, until it emits a solar flare that takes out our entire electrical system, which is a high probability event. In fact, there was a solar flare, I think, two days ago that's on its way to Earth, and no one knows what the consequence of that storm will be. Yeah.

Well, so it seems to me that in reality itself, there are something like levels of predictability that have something to do with statistical regularity. You know, the sun is a fairly predictable entity because of its immense mass and because of its immense mass and size, the transformations that it undergoes can be predicted to some degree at a statistical level. Reliably, but not entirely. I guess that's also partly. That turns us back to the reason that we evolved consciousness at all. Yes. If we could rely on induction, there'd be no reason for consciousness. Consciousness seems to be the mechanism that corrects for the fact that the world is not fundamentally predictable.

Like, seriously, not fundamentally predictable. irrevocably. Now, how do you understand, if at all. And this is where we start to wander onto the dangerous quantum territory. One of the things that's really struck me, and it's maybe only an analogy, is that the field, the Tohu Wabohu or the Teom, that the spirit of God that rests on the water. Yes. That field that that spirit interacts with seems to be something like the pool of infinite possibility. Like it's represented, for example, in the Mesopotamian stories. Absolutely. Yes, exactly.

As a dragon. Right. And a dragon is an interesting representation because a dragon is something fearsome and predatory, but also something that contains the possibility of treasure. And so the underlying metaphor there is that what our consciousness confronts is something infinite in danger and possibility. Right, right. Which seems perfectly reasonable. And that the proper stance to adopt to that is one of something like a heroic endeavor towards fundamental truth, and that. That's the best way of contending with that. And you see echoes of that in Genesis, because God is also periodically characterized as the victor of the battle over Leviathan, for example, which looks like an analog of Tiamat.

And so that's part of that heroic. Heroic interaction with reality that characterizes, well, the logos, the spirit of the logos itself. Right. The seething ocean of. Yeah. Okay. So at the quantum level, so what. What's being discovered? Right. Well, so this. I like to approach this through the debates that Niels Bohr used to have with Albert Einstein. So when quantum mechanics was first making itself known, first and foremost to these very men, among others, Bohr and Einstein were two of the great architects of quantum, along with Louis de Broglie and any number of. I mean, Max Planck we've already mentioned.

But it's between Einstein and Bohr that this fundamental irreducible tension emerges in which Bohr, sort of a Kantian philosopher, says, we're banging up here against the inherently unknowable to the human mind. Right, right, right. These waves in that describe probabilities. This is Schrodinger's sort of. And Heisenberg also kind of managed to mathematically describe probability waves which tell you where a particle is likely to be, but never where it actually is, not because we don't know, but because in some fundamental sense, it isn't in any of those positions. And this is Bohr's idea, Right. It's a possibility. It is possibility.

And Heisenberg at one point wonderfully compares it to Aristotelian potentia this ancient times. Really? Oh, yes. Oh, really? Oh, yes. Yes. To potential. Yes, to potential. Oh, that's so important to pure. Okay. And so brings back this old Aristotelian idea that the world is made of potential. Energea and the realization of potential. And so this is the Copenhagen interpretation, which basically says there are no holding places in your mind for that which is fundamentally unperceived. So Bohr is saying, of course, all of our measurements and observations are always going to be expressed in terms of classical mechanics because they're going to be making contact with our minds, which are shaped like classical mechanics in some way.

These categories like space and time, location and position, these are baked into our minds. This is where you get the Kant of it all. And Einstein wonderfully says, if this is true, then it's the end of physics, because to him, physics means it's deterministic. Yes. And it also means that mathematics describes directly a reality that is independent of us entirely, and that world can be blanketed over completely with these objective mathematical terms that describe whatever is most fundamentally real. And this dispute and its various tributaries are still going on today, which is one reason why this is such treacherous territory to venture into, because there's always going to be an alternative possible interpretation.

But if you accept something like Bohr's interpretation, which I believe remains the most philosophically coherent way of dealing with these discoveries, then what you have is a situation very much like what you're describing in Genesis. Now, that doesn't mean that the author of Genesis was told by God about the Schrodinger equations. That's sort of right. That would be the sort of pseudoscience version of it. But it does mean that the pattern you're observing shot through Genesis, and as you indicate through the whole Hebrew Bible, of God's mind as the resolver of a fundamentally unresolved possibility, the caster into order.

That's good. Or very good. Yes. And the idea of us as essentially the image of God in us is essentially. Yeah, okay, well, so let me extend that supposition for a minute. So there's a field of possibility that lays in front of you, and it, in a way, it surrounds and constitutes all the objects. So, for example, this is a candle, but not if I throw it at you. Okay. Right. Right. So there's a non zero possibility that one of the less probable manifestations of this object will occur. Yes. Okay, so then you might say, well, under what conditions does this remain a candle? Okay, well, that's very complicated. Yes. Because if I smash it, let's say, on the edge here, now, it's a knife.

Philosophy, Science, Education, Postmodernism, Quantum Mechanics, Perception, Jordan B Peterson