The video explores a personal journey of a systems engineer who transitions into the field of law, driven by feelings of unfulfillment. Initially feeling regretful about their engineering degree, societal feedback on their argumentative skills led them to law school through night classes at Birkbeck, a college of the University of London. Even though they gained substantial insights into law and its principles, they chose not to pursue a career in law, shifting focus instead towards political engagement and legislative roles to make impactful contributions to society.

political realization and transformation played a fundamental role in their career shift. At around 25, experiencing what can be described as a "quarter-life crisis" led them to question their career path and search for a vocation with a real societal impact. Their interaction with leftist ideologies and experiences during university, which they perceived as race-coded and low in expectations, ignited a passion for conservatism. Through exposure to various ideologies at law school, they came to appreciate conservatism, motivated more by personal experience rather than theoretical premises.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. jurisprudence [ˌdʒʊrɪsˈpruːdəns] - (n.) - The study or theory of law, encompassing various aspects of understanding legal systems and concepts. - Synonyms: (legal theory, philosophy of law, legal science)

And I do a law degree part-time, which was fascinating because I learned so much about the principles of all of the things we talk about, you know, the rule of law, jurisprudence.

2. quarter-life crisis [ˈkwɔːrtər laɪf ˈkraɪsɪs] - (n.) - A period of uncertainty and questioning that occurs in one’s mid-twenties, often involving doubts about one's career, relationships, and sense of identity. - Synonyms: (existential crisis, identity crisis, life crisis)

Do you know the term the quarter life crisis? No, I’m not familiar with that. But it sounds like you had one.

3. political [pəˈlɪtɪkl] - (adj.) - Relating to the government, public affairs, or the administration of public policy. - Synonyms: (governmental, administrative, civic)

But I love having this stuff in my head and I’d become quite political by that time.

4. vocation [voʊˈkeɪʃn] - (n.) - A strong feeling of suitability for a particular career or occupation. - Synonyms: (calling, profession, occupation)

And what I really was looking for was the vocation which I found in politics.

5. virtue signal [ˈvɜːrtʃu ˈsɪɡnəl] - (v.) - The act of expressing opinions or sentiments publicly that demonstrate one's good character or the moral correctness of one’s position on a particular issue. - Synonyms: (moral ostentation, tokenism, moral posturing)

They were not interested in the real problems and it was really a way for them to virtue signal.

6. moral colonialism [ˈmɔːrəl kəˈloʊniəlɪzəm] - (n.) - The practice of imposing one's own moral values and standards on another culture, often disregarding that culture's inherent values. - Synonyms: (ethical imperialism, cultural imposition, values imposition)

An irritation with what I call moral colonialism where rather than focusing on growth and how to make these countries self sufficient, we sort of preach values.

7. institution [ˌɪnstɪˈtuːʃn] - (n.) - An established law, practice, or organization in a particular community or system. - Synonyms: (establishment, organization, foundation)

You learn the power of institutions. You see how you need to preserve institutions from generation to generation.

8. conservatism [kənˈsɜːrvətɪzəm] - (n.) - A political and social philosophy that promotes retaining traditional social institutions and values. - Synonyms: (traditionalism, right-wing politics, preservationism)

So many things took me on the journey to conservatism.

9. hierarchy [ˈhaɪərɑːrki] - (n.) - A system or organization in which people or groups are ranked one above the other according to status or authority. - Synonyms: (ranking, order, pecking order)

I wasn’t there in the hierarchy of Fulfillment.

10. radicalism [ˈrædɪkəlɪzəm] - (n.) - The beliefs or actions of individuals, groups, or movements that aim for fundamental societal change by radical means. - Synonyms: (extremism, militancy, revolutionism)

So I had that radicalism, that radicalization process.

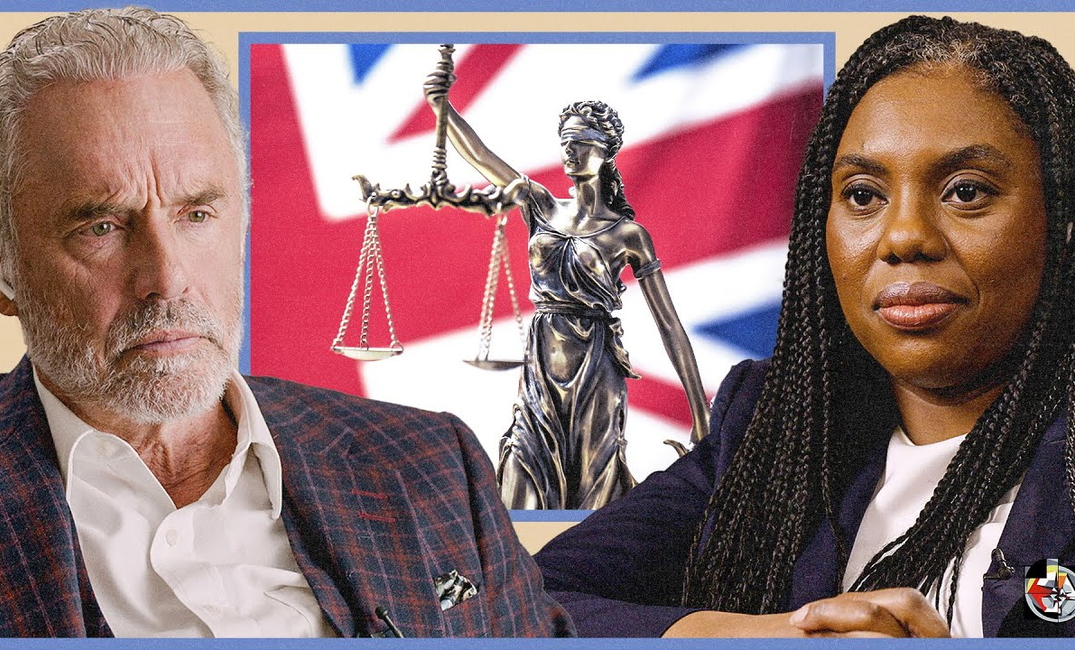

Moral Colonialism - Kemi Badenoch

Okay, so now you studied systems engineering, but then you went to law? Yes, so after I finished my university degree and I did a longer degree, I did a four year engineering degree rather than a three year one. Where was that? At the University of Sussex, which is on the south coast of England.

And you know, after university everybody disappears. You all go off to different places, you get different jobs, different parts of the country. And I just had this feeling that of unfulfillment. And I thought I've made a mistake, maybe I shouldn't have done engineering, maybe I should have done something else. And everybody says, you know, I speak very well and I make good arguments, I should have been a lawyer.

So I went to was really night school. I went to the University of London, but they have a college called Birkbeck where the classes are in the evening. And so I went to night school while working about 2005, so I'm about 25 and I do a law degree part time, which was fascinating because I learned so much about the principles of all of the things we talk about, you know, the rule of law, jurisprudence, but also a lot of the history of the UK which I would have learned had I gone to primary or secondary school here. I learned in my law degree and it was just so amazing.

And at the end of it I thought I don't want to be a lawyer, definitely don't want to be a lawyer. But I love having this stuff in my head and I'd become quite political by that time and I was more interested in helping to make good law, so being a legislator than being, you know, a corporate lawyer or something like that.

Okay, so how did you become political and why did you decide that you weren't going to be a lawyer? Well, I think. Do you know the term the quarter life crisis? No, no, I'm not familiar with that. But it sounds like you had one. Yes, I think I had a quarter life Crisis, sort of 25 and I've done everything I'm supposed to do.

You know, you finish primary school, you finish secondary school, you do your A levels, you get your degree, you get a job. I had a good job. I was working in consulting and I still wasn't happy and I was looking, I didn't know what I was looking for, but I knew I was looking for something and I thought another degree would give it to me. And what I really was looking for was the vocation which I found in politics.

And it was a long journey over. Prob. From age 16 onwards, having that experience of the, you Know that low expectation culture which I thought was very race coded and looking back on it, it was extremely race coded. If I was, I think a white child I would have been treated differently. And again it was sort of left wing teachers who were trying to be helpful but actually creating a lot of destruction along the way.

That experiences at university where I think I met my first sort of proper left wing student culture type person and I did not like it. I thought they were very ignorant because by this time of course I know a lot about Africa. And they talked about Africa as this place where they would come in and help the people, you know, who were, you know, just these helpless people, no agency whatsoever.

They were not interested in the real problems and it was really a way for them to virtue signal. And I found that so aggravating and, and that also semi radicalized me around what we do with aid, for example, and how we let a lot of African countries get away with things that they shouldn't do. An irritation with what I call moral colonialism where rather than focusing on growth and how to make these countries self sufficient, we sort of preach values which the west has come to after a long period and try and impose them in places where there's no, you know, they're not ready to receive them or interested and not engaging with people on that level.

So I had that radicalism, that radicalization process and that was actually my first work with the Conservative party. So it's 2005, I'm 25, 2006. David Cameron sets up these policy commissions and one of them was called Globalization and Global Poverty. And I really cared about this subject because I thought a lot of money was being wasted and sent to places where it shouldn't be sent to when actually what people needed was partnerships, business, more sensible, more sensible ideas.

And it was supposed to even back then in 2006 onwards it was how do we tackle globalization, how do we make sure it works for everyone else? But these things end up getting co opted always by, you know, vested interests and which is a real shame.

So many things took me on the journey to conservatism. I think also culturally I am a Christian. I don't believe anymore. I used to, there was something changed, Something happened about 2008 which changed my views on Christianity. But still I am culturally a Christian. My grandfather was a reverend in the Methodist church. I went to a Church of England school.

And many of the things that are formative in my experience, singing hymns and you know, knowing them off by heart and just a lot of the Stuff that you end up doing in an African country, almost all of which are very religious, can shape you.

And I find the interpretation of Christianity in the UK quite interesting compared to certainly Africa and Nigeria. People believe that it's not just something you do on a Sunday. The Bible is a living word of God and you have to do all these things. And of course they're inconsistent and there are all sorts of hypocrisies.

But, you know, growing up in a country that was genuinely multicultural, half the people were Muslim. We had both Christian and Muslim prayers in my school. You look at the behaviors and so on, you just get a lot of insight into religion as an aspect of culture. Religion in my view, is downstream of culture. It's not upstream. And I think people not understanding that is why there are a lot of. I have a lot of critiques about the way people speak about religion, Islam in particular in, in this country. I don't think they understand it. I think that they, they miscategorize a lot of people in a way that should not happen.

Okay, well, we'll definitely going to, we're definitely going to return to that. And so you're at law school now. You're doing that at night. What are you working? How are, what are you, what are you doing as a job during the day? I'm working as a systems analyst for a company that no longer exists. It was called Logica. It was quite big at the time. It was a sort of dot com boom software company.

And it was fine and I was earning good money and saving. I had enough. Earning enough to save for a house deposit. It was okay, but I wasn't there in the hierarchy of fulfillment. Right.

And so you went to law school part time and you found that compelling intellectually, but you also. Is that where you ran across your, your leftist nemesis and, and first started to understand what the pathologies of the, of postmodern postmodernism that, that kind of sly Marxism that's a part of that. And why did that strike you so intensely?

Like you tangled that together a little bit in your self description with that bigotry of low expectations that you encountered with the more leftist teachers. And so that's all percolating, but it sounds, there was some actual striking experiences that perhaps you had in law school that politicized you. And it also sounds like your politicization in part was, at least initially. I definitely don't want that. Right?

Yes, very, very much so. Well, so let's walk through that because I'd like to disentangle that there's the bigotry of low expectations that you described and that deviation that you had in your academic striving in consequence. And now you're at law school and what are you seeing among the leftist students there? And why is that raising your hackles?

So actually what I saw started before law school, but I just couldn't define it. It was the stuff that I saw when I was studying engineering with those students. That was the first degree. And I had just a very dim view of a lot of the students studying the humanities courses because they didn't need to work as hard as those of us studying engineering.

I think I had about 26 hours of, you know, teaching time and lab time. You know, we were in the laboratory all the time. And then you had these people studying arts and they were all sort of, you know, just messing around all the time. They were acting plays and having lots of fun and going on demonstrations and protests.

And I thought, where do they have time for this? And they were all so sort of smug and condescending. So I realized, well, I don't like this. And because I have the self confidence of growing up in a relatively wealthy family, I don't feel intimidated by them and I challenge them. I have arguments with them and they lose and they get angry.

And I think that they are just very weak people who don't like arguments. And they say things like, well, you can't say that, or how can you? How can you say that you're black? You should know that, you know, all these people are racist and we're just trying to be helpful and so on. And they were so condescending. So I know I don't like that.

I also know that I don't like teachers who just set very low expectations. I'm learning that family has actually been the most important thing in making me who I am. And I didn't realize that long enough. So all of these things are taking me on the journey to conservatism.

Then I do the law degree where I'm reading about John Stuart Mill and Edmund Burke and how the rule of law is so critical to, you know, the west, but how this country functions and you learn the power of institutions. You see how you need to preserve institutions from generation to generation. You then compare with what happened during the colonial era where institutions are brought and, you know, dropped in a place.

And so yes, there's now a common law tradition, but the culture has really changed. And eventually the culture erodes it. So a lot of it is personal experience and Observation and lots of arguing. So I loved arguing, loved debating.

And I remember when I was in that job working as a systems analysis, there was a lefty French guy who worked with me, and he kept saying, you are so right wing. You are so right wing. And I didn't know enough then. And I said, no, I'm not right wing. Because right wing, as I had been taught, was a bad thing.

You know, the media, the cultural establishment always used right wings as a pejorative term. So I would say, no, I'm not right wing, but I was. And I remember when I really sat down and read the canon and the text, and, you know, you read Hayek and of course, Thomas Sowell, who I love very much, I realized, oh, my goodness, I'm very right wing, and I'm proud of that.

This is not something to be embarrassed or ashamed about. And my being very much on the right is that mix of the cultural conservatism, because I want us to preserve the things that are amazing here. And one of the things that is amazing is the classic liberalism, not the postmodern sort of corruption of that. And a lot of what I see that has gone wrong is the corruption of liberalism.

And I gave a speech in December where I said, liberalism has been hacked. The people have found the weakest points and are twisting it to do things it shouldn't be doing. And you need muscular liberals to defend their turf. And instead what they've been doing is giving away their turf.

And that is how we ended up with a lot of the extreme gender ideology coming into play, because it wore the clothes of the gay rights movement. It's nothing like that.

And that's how we saw a lot of the craziness of critical race theory. The BLM movement set race relations in a terrible negative territory, but it wore the clothes of the civil rights movement. And you need people who are in touch with reality who can say, no, this is not real, this is not true.

And I think that is something which I am lucky to have, that I just don't get detached from everyday life. I know what is real and what isn't. And I am amazed that we have politicians, including the British Prime Minister, who will say things like, 99% of women don't have a penis, as if 1% of women do.

And if a politician is prepared to tell you something that we all know is not true, then what else will they tell you? Even creatures without nervous systems can distinguish between the sexes. And so, yeah, there's something very pathological going on there.

EDUCATION, POLITICS, PHILOSOPHY, LAW EDUCATION, CULTURAL CRITIQUE, PERSONAL GROWTH, JORDAN B PETERSON