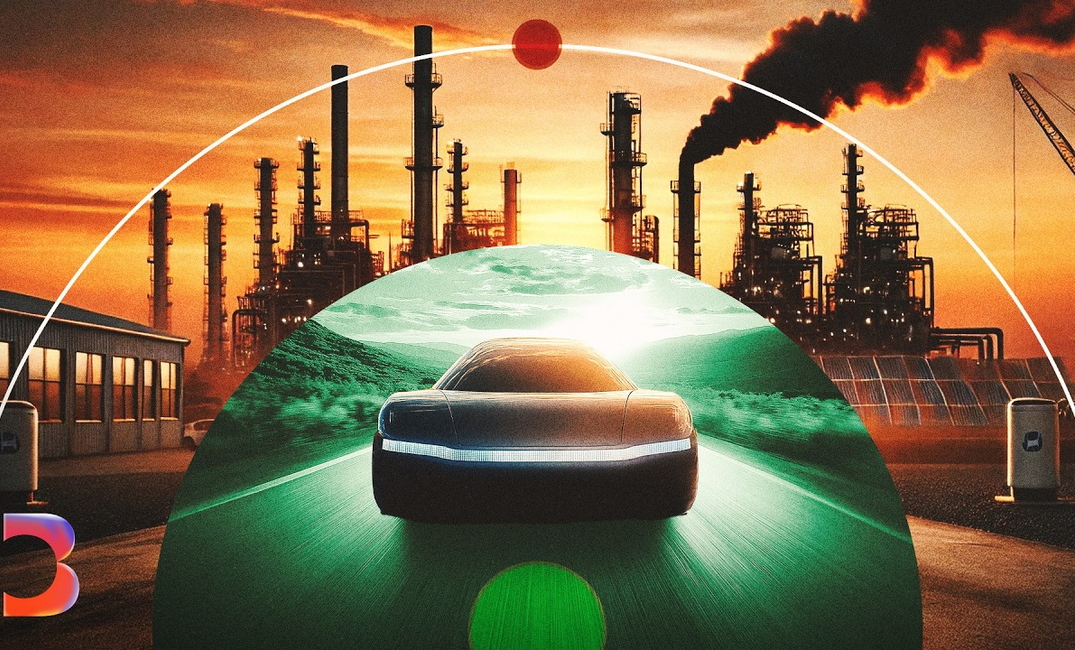

The video highlights a groundbreaking project in East Germany, attempting to transition from fossil fuels to hydrogen energy, offering a glimpse into the potential future of global energy. This effort represents a significant step in adopting hydrogen as a key player in achieving climate neutrality. However, there are significant barriers including high costs and the necessity for government subsidies to make such transitions viable. The video questions whether these large-scale shifts towards hydrogen energy are feasible given current technological and economic limitations.

The discussion extends beyond Germany, focusing on a now-abandoned hydrogen trial in Redcar, UK, which highlights the challenges of adopting hydrogen in residential settings. The trial was eventually canceled due to community opposition and inadequate groundwork for public acceptance. This underscores the necessity of public engagement and education in implementing new energy initiatives. There is also skepticism surrounding hydrogen's efficacy and safety when used broadly, fueled by limited evidence supporting its role in reducing emissions effectively.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. transition [trænˈzɪʃən] - (noun) - A change from one state or condition to another. - Synonyms: (change, shift, conversion)

This bright yellow power plant in East Germany is at the forefront of the green energy transition

2. emissions [ɪˈmɪʃənz] - (noun) - Substances, typically gases, released into the air. - Synonyms: (discharges, pollutants, releases)

Its aim is to go from using polluting fossil fuels to emissions free hydrogen in just two years

3. neutrality [njʊˈtrælɪti] - (noun) - The state of not supporting or helping either side in a conflict or disagreement. - Synonyms: (impartiality, nonalignment, equidistance)

Clean hydrogen is a perfect means to towards our goal of climate neutrality.

4. subsidies [ˈsʌbsɪdiːz] - (noun) - Financial support given, usually by a government, to make a product or service more affordable. - Synonyms: (grants, allowances, financial aids)

Clean hydrogen subsidies are set to top $360 billion globally this year.

5. infrastructure [ˈɪnfrəˌstrʌktʃər] - (noun) - The basic physical and organizational structures and facilities needed for the operation of a society or enterprise. - Synonyms: (framework, groundwork, system)

But using the same infrastructure that we already have, governments across the world are rushing to scale up the technology.

6. opposition [ˌɒpəˈzɪʃən] - (noun) - Resistance or dissent toward a proposal or practice. - Synonyms: (resistance, objection, disapproval)

The trial was expected to start in 2025, but northern gas network eventually pulled the plug on the project after months of strong opposition from local residents.

7. pragmatic [præɡˈmætɪk] - (adjective) - Dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations. - Synonyms: (practical, realistic, utilitarian)

While hydrogen can play a part in reaching net zero, a more pragmatic approach could offer benefits sooner.

8. misinforming [ˌmɪsɪnˈfɔːrmɪŋ] - (verb) - To provide someone with incorrect or misleading information. - Synonyms: (misleading, deceiving, lying)

There's documented history of decades of misinforming, disinforming, trying to pretend climate change doesn't exist.

9. exacerbating [ɪɡˈzæsərˌbeɪtɪŋ] - (verb) - Making a problem, bad situation, or negative feeling worse. - Synonyms: (aggravating, worsening, intensifying)

And climate change is exacerbating the effects of extreme weather globally.

10. engagement [ɛnˈɡeɪdʒmənt] - (noun) - The action of engaging or being engaged. - Synonyms: (involvement, participation, association)

The discussion extends beyond Germany, focusing on a now-abandoned hydrogen trial in Redcar, UK, which highlights the challenges of adopting hydrogen in residential settings.

The Dirty Secret Behind the Green Hydrogen Push

This bright yellow power plant in East Germany is at the forefront of the green energy transition. Its aim is to go from using polluting fossil fuels to emissions free hydrogen in just two years. And that would make it one of the first in the world. We're really convinced that hydrogen will play a major role in the future. Facilities like these are part of a dream energy system sketched out by policymakers across the world. Clean hydrogen is a perfect means towards our goal of climate neutrality. But does this hydrogen dream come at too high of a cost?

To be quite honest, without any support schemes, we can't afford to transform this operation from natural gas into a hydrogen operation. I think we are tying our hands and we are making it impossible to hit net zero on an accelerated timeframe. We've got a problem with climate change and we need to solve it. And along comes this thing that seems like it ticks all the boxes. Heat pumps are hard. Changing people's cars, it's hard. Hydrogen, fabulous. That's easy. Hydrogen is a gas, and a lot of companies and governments see it as a way to replace natural gas. But using the same infrastructure that we already have, governments across the world are rushing to scale up the technology.

Clean hydrogen subsidies are set to top $360 billion globally this year, up 71% since 2022. But even that might not be enough. Europe aims to ramp up production to 20 million metric tonnes by the end of the decade. Bloomberg NEF forecasts it will only hit 2.81. Green hydrogen currently costs three times more than natural gas. When you look at hydrogen, it could be this amazing solution for the future. But really, when you dig into it and when you take a closer look, the time scales are long, the budgets are huge, and the technology isn't working in a lot of places yet, so we don't see it on the ground.

This is Redcar, a tiny seaside town in the northeast of England chosen to be the site of an experimental hydrogen heating trial a few years ago. As well as fueling power plants, advocates want hydrogen to heat our homes, another source of emissions. The trial was expected to start in 2025, but northern gas network eventually pulled the plug on the project after months of strong opposition from local residents. The excuse given was that there wasn't enough hydrogen. But to be honest, it was never going to happen in any case, because the basic work of getting people to accept what was coming down the tracks had not been done.

The first knowledge I had of the Redcar trial was leaflets and advertising through doors. And initially it was quite enticing. You will be given new boilers, new cookers, new appliances. And that was the kind of the selling point. The more questions were asked and the less answers were given. It just became very alarming. Hydrogen is a dangerous gas. We handle it very well in industrial environments, but we do it through an enormous amount of safety precautions. So when it came to Redcar, NGN said, no, we're not going to knock holes in people's walls. We're going to use a hydrogen sensor.

Most hydrogen professionals are aghast at the idea that we would be putting hydrogen into homes in the UK. We're not dinosaurs. It wasn't that we weren't all for progress, it was just, you know, we all know that it hadn't been tried properly. It's quite insulting, really, to think that they just thought we wouldn't fight back, we wouldn't do anything. We'd say, we're just backward, not. It just proves what can happen when a community work together, stand together and say, no, you were not listening to us, you will listen to us and we're not putting up with it.

How do you like them apples? What Redcar really shows us is that you need to get people on board from the very beginning. You've got to bring people with you, whether it's heat pumps, whether it's hydrogen, whatever it is. You can't roll something out without talking to people first and making them believe in what you're trying to do. There's been 58 independent reports. Not one comes out saying anything other than a minuscule or no role for hydrogen and heating. And that raises the question, why is it still being promoted so heavily, the force behind the government subsidies? It's recent. It really is not coming from energy experts outside of the oil and gas industry. It's coming from the oil and gas industry itself.

Robert Howarth has enemies in the oil and gas industry due to his research questioning how clean hydrogen really is. There are several different types of hydrogen. While green hydrogen comes from renewable sources, it only makes up 1% of the total hydrogen mix. The majority of hydrogen we make today is a byproduct from fossil fuels, releasing greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. Although still categorized as clean, blue, hydrogen is made using natural gas, but only some of the emissions are captured.

Oil and gas industry is an incredibly powerful force in our universe. There's documented history of decades of misinforming, disinforming, trying to pretend climate change doesn't exist when they know it does, trying to pretend it's not caused by them when they know it was. Blue hydrogen's a dirty product. The greenhouse gas footprint of blue hydrogen is actually larger than that of simply burning natural gas. Over the past couple of years, big oil has been jumping on hydrogen, and the companies have started to heavily invest in the technology's success.

2018, Shell, total, British Petroleum, other big majors set up this thing called the hydrogen council. It's a huge part of the revenue stream for big oil and gas. So, you know, when you call into question whether or not we should be using that fuel at all, that's going to be problematic for them. Right. Billions are being poured into a technology that could actually be adding to our climate woes. While the stakes have never been higher, 2024 is on track to be the hottest year on record. And climate change is exacerbating the effects of extreme weather globally. And the electorate feels it.

A lot of politicians need an answer to climate change. Young people expect it, and some of the answers are really difficult. If the ones you have are difficult, would require sacrifices, would require costs, it's much easier just to say, oh, it's going to be hydrogen, and if it works or doesn't work, we'll only find out in a decade anyway. But the fact is, we don't have decades to get to net zero. Unless hydrogen becomes considerably cheaper, our climate policies might need a rethink. There's no route to net zero that doesn't go through clean hydrogen, but we need to be realistic.

They call it the swiss army knife of energy. You can do everything with it, but of course, just like with a swiss army knife, just because you can cut your hair with it, you don't. You can butter your bread with it, but you don't. While hydrogen can play a part in reaching net zero, a more pragmatic approach could offer benefits sooner. Ten years ago, we decided to get rid of the oil furnace and we replaced it with these ground source heat pumps. It's modestly expensive to put in initially, but over the ten years since we've put it in, we've more than paid back the system.

Here in the state of New York, the number one source of greenhouse gas emissions is the emissions that we use for heating our homes and our commercial buildings. Once up and running, the hydrogen plant in Leipzig will have two turbines, each producing 62.5 clean power, barely scratching the surface of what's needed. The german authority predicts they could require up to ten gigawatts to reach net zero. Building all this infrastructure needed for hydrogen is a big gamble. We're going too slowly, and we can't really afford to lose several years looking at a technology that later we don't use.

I think what's really at stake here is net zero. And from what we've seen from reporting this story, there isn't really a plan b. It's just hydrogen or fossil fuels.

Innovation, Global, Technology, Hydrogen Energy, Fossil Fuels, Climate Change, Bloomberg Originals