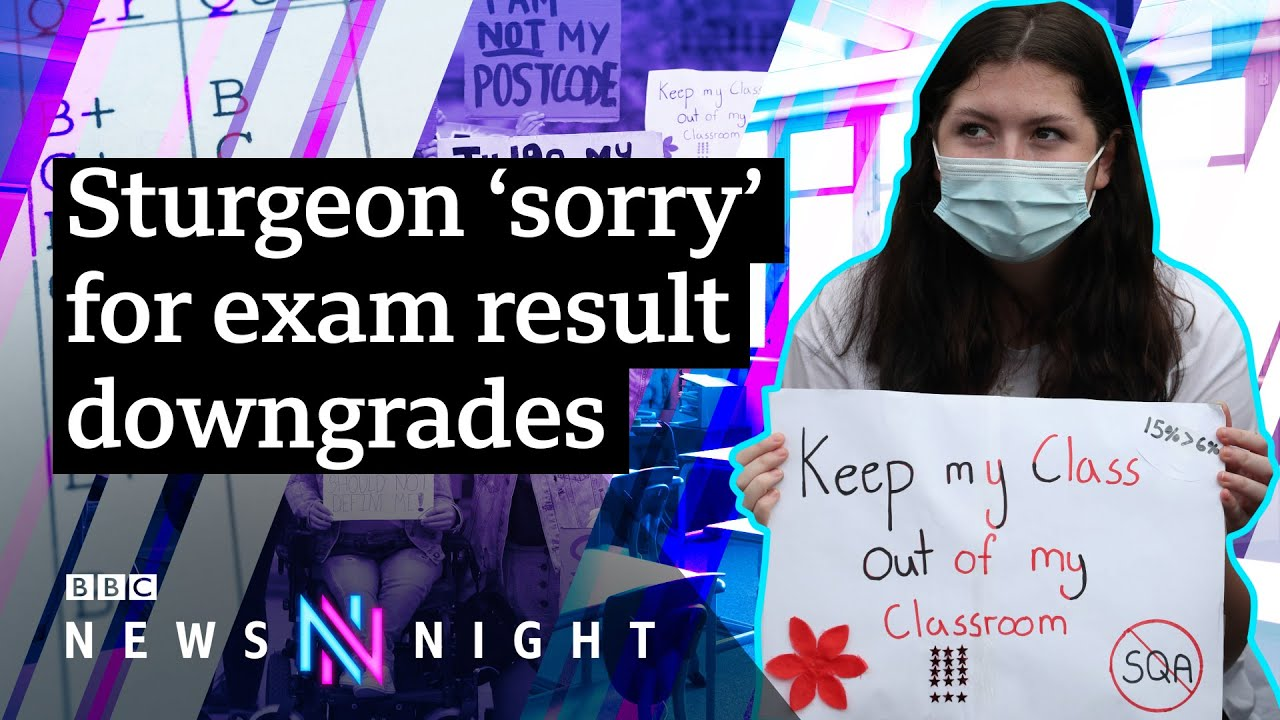

The video discusses the current controversy in the UK surrounding the grading system for students, especially focusing on the Scottish government's approach amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Amidst criticism, students, particularly from deprived areas, have been adversely affected, sparking political apologies and calls for changes in the grading methodology.

The conversation highlights the perceived unfairness of using algorithms to standardize student grades, which are largely based on past school performance, potentially disadvantaging students in less affluent areas. The panelists discuss whether this truly reflects students' capabilities and the broader implications for inequality in the educational system.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. apology [ə'pɒlədʒi] - (noun) - A statement expressing regret for an error or offense. - Synonyms: (acknowledgment, expression of regret, confession)

Less usual, though, is a political apology, but the first minister has faced mounting criticism over scottish exam results and the technique used to decide grades

2. algorithm ['ælgərɪðəm] - (noun) - A step-by-step procedure or formula for solving a problem. - Synonyms: (procedure, process, method)

The students in the year before got. You know, there is a moral dilemma there that how can you allow for school improvement when you're just using an algorithm that spits out results based on prior cohorts achievement.

3. deprived [dɪ'praɪvd] - (adjective) - Suffering from a severe lack of basic material and cultural benefits. - Synonyms: (disadvantaged, underprivileged, impoverished)

Students in deprived areas have been hit much harder than those in affluent parts.

4. injustice [ɪn'dʒʌstɪs] - (noun) - Lack of fairness or justice. - Synonyms: (unfairness, inequity, discrimination)

You have individuals who are being let down by an injustice system and it's completely wrong.

5. robust [rɔ'bʌst] - (adjective) - Strong, healthy, or vibrant approach or framework. - Synonyms: (strong, sturdy, durable)

Ofqual has developed a robust process that will take into account a range of evidence, including grades submitted by schools and colleges.

6. criticism ['krɪtɪsɪzəm] - (noun) - The expression of disapproval based on perceived faults or mistakes. - Synonyms: (censure, disapproval, condemnation)

But the first minister has faced mounting criticism over scottish exam results and the technique used to decide grades.

7. recalibration [ˌriːkælɪ'breɪʃən] - (noun) - The act of adjusting or fixing something by modifying its scale or parameters. - Synonyms: (adjustment, correction, readjustment)

Do you get any sense, Larissa Kennedy, that there might be some kind of recalibration for Thursday, or is this done?

8. affluent ['æfluənt] - (adjective) - Having a great deal of money; wealthy. - Synonyms: (wealthy, prosperous, rich)

Students in deprived areas have been hit much harder than those in affluent parts.

9. entrenches [ɪn'trentʃɪz] - (verb) - To fix firmly or securely. - Synonyms: (establishes, embeds, reinforces)

Do you think the danger is that that entrenches inequality?

10. bumpy ride ['bʌmpi raɪd] - (noun phrase) - A scenario involving difficulties or challenges. - Synonyms: (difficult time, rough patch, tough journey)

But for the class of 2020, the COVID generation, it's likely to be a bumpy ride.

The Covid Generation - Will disadvantaged pupils be downgraded in the rest of the UK? - BBC Newsnight

Morning. In these Covid times, frequent hand sanitizing is the norm, and Nicholas Sturgeon certainly kept her hands clean at a school in west Calder today. Less usual, though, is a political apology, but the first minister has faced mounting criticism over scottish exam results and the technique used to decide grades.

Higher's students are furious. Already penalized by cancelled tests, the country's exam body then lowered 125,000 of the grades that have been estimated by teacher assessment. Students in deprived areas have been hit much harder than those in affluent parts. Today came the first minister's mayor culpa. Despite our best intentions, I do acknowledge that we did not get this right and I'm sorry for that.

Tomorrow, the scottish government will announce how it plans to fix the problem, as England, Wales and Northern Ireland prepare for a level results on Thursday and GCSE's the following week that have been determined using a similar adjustment system at a school like this one in a deprived part of north London. They are expecting a repeat of what's happened in Scotland and are planning appeals on behalf of disadvantaged students who were downgraded.

Head teacher Alan Streeter took charge of a struggling school two years ago and is already making progress. But in the absence of real exam results, like everywhere else this year, Beacon Highs GCSE's will be based in part on the school's previous performance. It's immoral that all of that work for the five, or not quite five years that they were at school then amounts to what the students in the year before got. You know, there is a moral dilemma there that how can you allow for school improvement when you're just using an algorithm that spits out results based on prior cohorts achievement.

Overlooked by social housing, Beacon High receives government pupil premium funding for nearly 70% of its students to help teachers improve attainment for disadvantaged kids. Samira should have sat her GCSE's this summer. Instead, the would be medic will come to school next week to be told what's been decided on her behalf. Closer I get to the results day, the more stressed I get. Can you justify them? Are they going to be fair? And it's. It's just you don't. You don't know what you're going to get.

You know, we're here at like a dis, what's considered to be a disadvantaged area, and we're going to get the lower grades with, you know, it has an impact on all of our lives. What do you think about that? Personally, I think it's quite unfair. Your intelligence isn't based on where you live. These are inequalities that already existed, but the optics are much worse when it's a system, an algorithm that is deciding people's place in that system.

The Sutton Trust has research out later this week that shows almost a third of university applicants polled in England, Wales and Scotland. They're less likely to get into their first choice university as a result of the pandemic. But don't despair, there will be a big drop in international students seen at universities next year, and many universities will be kind of looking to fill those places with uk students. So actually, even if young people are disappointed with their results that they receive this Thursday, there is huge scope through the clearing system, for there will be many more opportunities this year available to them because of that.

And actually the odds are in their favor in that respect. England's exam board has said if it hadn't standardized A level, results would have been 12% higher than last year. But for the class of 2020, the COVID generation, it's likely to be a bumpy ride.

Katie Razor, the Department for Education in England, told us Ofqual has developed a robust process that will take into account a range of evidence, including grades submitted by schools and colleges, with the primary aim of ensuring grades are as fair as possible for all students. We did ask both the UK and scottish governments for a representative to discuss this, but they declined.

Joining me now is Larissa Kennedy, president of the National Union of Students, former education minister Robert Goodwill, and Sir Michael Marmot, professor at UCL and author of the Marmot review into health inequality in England. First of all, if I could begin with you, Robert Goodwill.

You know, in Scotland we had a situation where, for example, several pupils maths hires prelims a results, actual results de results. It's roughly the same system. Is this really the best way to treat teenagers who have already been disadvantaged by being out of school for their education? Well, we're not going to see results drop by that amount. Generally, it will be on the margins of between two grades.

And indeed, the task before us is to try and get the results that the students would have got how they sat exams. And using the example of the previous year to assess what a school is likely to perform like is probably no bad thing. Indeed, you just mentioned the figures there that the teacher assessments have shown that there's a twelve percentage point increase in a levels at a grade and above, and at GCSE, a 9% increase in grades grade four and above.

And the process of standardization is to bring those back into line because that's only going to be fair for the students who took their exams last year, and particularly for the students who take their exam next year. We need to make sure we have them, and I want to interrogate that. But I just want to pick up something you just said there. You're going to look at the school's overall performance.

This is an algorithm. This has got absolutely nothing to do with individual pupils endeavours. That is wholly unfair. Well, the teachers themselves have carried out the centre assessment grades within the grades. They will assess the children and rank them in order within those grades.

So this isn't an arbitrary system, this is adjusting the grades to fit with the expectations for this year. We've never had a situation that we've seen a 15% or 9%, 12% increase year on year. As it turns out, with the standardization, we will see an increase. There'll be a 2% increase in a grades and above and a 1% increase in those top GCSE grades.

So students will be getting better results than they were last year. But when we go back to exams next year, we're going to have a whole new tranche of students taking those exams. It's only fair for those students that they're going to be assessed at the same level, so we don't see a massive grade deflation next year, when they actually take exams next year, of course, doesn't really matter to these pupils.

Larissa Kennedy, is there merit in looking at the school's overall performance last year to judge the outcomes for these pupils this year? There absolutely is no merit in looking at prior performance, because exactly as we're seeing, this is just baking inequality into the system, as has just been said. You know, they're just trying to fit students attainment against a prior year, which means you're actually assuming and reproducing the fact that students from low socioeconomic backgrounds are, as this system would say, are due to get lower grades.

And if we're actually saying that that's a just system, if that's the state of the education in this country, then it's a grave shame and a grave injustice to those students who haven't had the opportunity to do well. I mean, you heard in the film the young woman saying, my intelligence isn't based on where I go to school.

So why do you think the off call has used that algorithm? I think it's a lazy move. It's a lazy move because it's something that we can now say, oh, yeah, this is what happened last year, so we can build on it. We can say that that's the case, but no, that's not the case.

You have individuals who are being let down by an injustice system and it's completely wrong. So, Robert Goodwill, you talked about what the government had told you, and this was an internal letter as well from the education minister, Nick Gibb. If we didn't moderate students predicted grades, they'd be 12% up and last year. And that's unfair to last year and next year.

That's essentially what you were saying to what is wrong? What is actually wrong? It could be absolutely brilliant teaching. I mean, it's perfectly reasonable to think that maybe teachers might be erring on the side of optimism.

But what is wrong with grades being 12% better? Wouldn't you be celebrating that about the education system? Well, if that reflected an unprecedented 12% increase in the performance of schools, you know, we have seen increasing performance in schools. We've seen a closing of the attainment gap.

And could I just reassure Larissa, there will be no widening of the gaps between disadvantaged children and other children, no widening of the gaps between BAME children in the way these have been produced. But let's not forget that these children taking their a levels this year were in the same school last year when those exam results were produced by their predecessors, Sir Michael Marmot.

In Scotland, the downgrades were about 15% in disadvantaged areas, 6% in affluent areas. If the system is the same, roughly in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, do you think the danger is that that entrenches inequality? I think it compounds the disadvantage.

So what we know generally, and it's a very tight relationship, the more deprived the area, the less well do children do, on average. Not necessarily exactly as the person your film said, because they have lower intelligence, but it relates both to family background, the general social background and the schooling. So that's one disadvantageous.

Secondly, with Covid-19 and with closing of the schools, more deprived kids have bigger disadvantage from closing of the schools than kids from more advantaged backgrounds. So that will increase the inequality in educational performance.

So then, to have a moderating system that actually disadvantages children from disadvantaged areas more than the other seems entirely wrong. You would imagine, correcting it in the other direction because of the adverse impact of lockdown.

So, Larissa, there's two things. The first thing is that in Scotland, obviously, there's going to be a big announcement tomorrow about actually changing what's happened, but appeals by pupils, by and large, they're saying, would be individual. With the school now, in England, the system is going to be, the school would have to appeal and it would only be on a technical grounds, am I right?

Yes. So it'd be based on whether or not the process has been done correctly. And for disadvantaged pupils, does that doubly disadvantage them, because many disadvantaged pupils maybe don't have the confidence, apart from anything else, to come forward and actually make a fuss.

I think we've actually got a triple whammy in terms of how people are being disadvantaged, because you've not only got potentially being marked down just based on your postcode and this postcode lottery affair going on, which is a seeming already unjust system, we've then got the fact that, you know, people are being told you might be able to reset, but you might have to pay for that as well.

We don't have yet assurance on whether or not that's going to be free, and then you've got people potentially missing out on their university places. So I think there are so many elements to this that are just furthering the disadvantage that we already see in education.

So, Robert Goodwill on that point, aren't thousands of people going to feel like failures? And anyway, why shouldn't they get a break when they were promised laptops, many of them didn't get them, when many people didn't have Wi Fi, when there's actually also going to be many empty university places because we may have a drop in international students due to the pandemic. Surely this is the year to make sure kids get as much advantage as possible when they've been so disadvantaged.

Well, the impact of lockdown will not have an impact on the children that would have taken exams this year. They could have a major impact on children taking exams next year, which is why it's very important we get the children. It would have an impact because they will not be actually having been in class, getting the full panoply of the lessons that they would have got had they actually been in the physical school.

But the teacher assessment on which these grades are going to be based are based on the performance before lockdown. The point I'm making is that the children we really need to worry about are ones that missed out on school. We're going back to school in September. We need to get them back into school to make sure they can make up for lost time.

Sir Michael, doesn't Robert Goodwill have a point, though, that if you adjust or over adjust for this year, then you are causing problems for next year and you are putting out of kilter with pupils from last year? Of course we want to get consistency in grading, no question about it. But if the adjustment leads to bigger downgrading in deprived areas, then we have to ask serious questions.

As the first minister of Scotland has acknowledged, we have to ask serious questions if we're doing the adjustment in the right way and if it's based on average performance of the schools in previous years. Baking in the disadvantage. That's saying we know kids from deprived schools do worse, so we'll downgrade. Yes, you're baking in disadvantage.

Robert Goodwill. I think the way to address disadvantage is what we've been doing already that's having better quality teaching, having our early years programme with 30 hours free education for younger children, the three year olds getting their 15 hours, improving the standards of teaching. My own constituency is an opportunity area where the government giving them money to improve the standards of schools. So we need to actually improve the education that we're delivering now.

We have closed the attainment gap, we need to make more progress continuing to do that. Larissa Kennedy, can I just. Because we're running out of time here and that very much is in the future, understand that. Robert Goodwill. But actually, in this moment, there'll be pupils hopefully watching this program going, what am I going to do about Thursday?

Do you get any sense, Larissa Kennedy, that there might be some kind of recalibration for Thursday, or is this done? I am really, really urging students to demand that recalibration, to demand that, you know, we don't accept a classist, racist system of education, that we call on the government to ensure that appeals are fair, are equal and are easy to access, that universities are keeping those places open, that students are able to resit for free, and that we actually do a whole scale reassessment of this system, not only this year, but into the future. Thank you all very much indeed.

Education, Politics, Inequality, Technology, Uk Exams, Covid-19 Impact, Bbc Newsnight