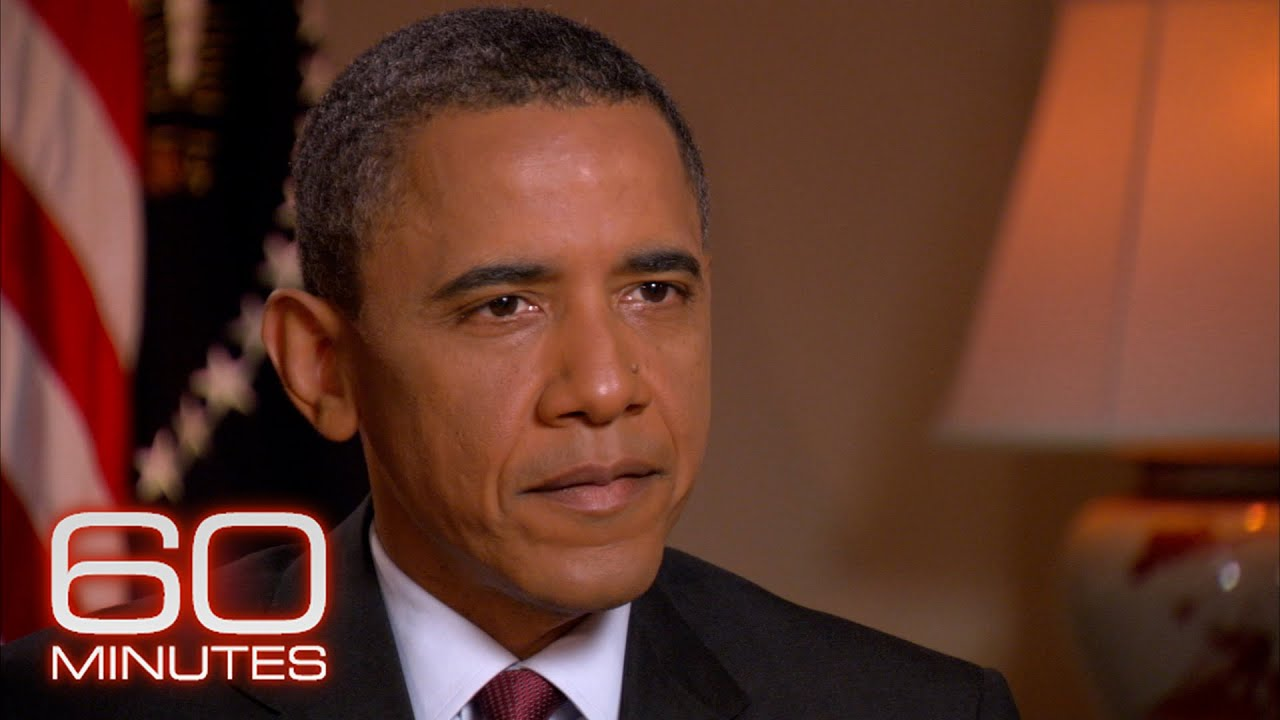

The video dives deep into the operation that led to the killing of Osama bin Laden, showcasing the meticulous planning and execution carried out by the U.S. government and its intelligence agencies. President Obama reveals first-hand insights into the high-stakes decisions that had to be made, the operational secrecy, and the challenges faced in executing the raid without prior knowledge of the Pakistani government.

The video is a significant exploration of a pivotal event that had far-reaching implications not only for U.S. national security but also for international relations, particularly with Pakistan. President Obama explains the strategic reasoning behind not informing Pakistani authorities and details how cooperation with them was vital in the broader context of counterterrorism efforts. The narrative captures the tension, risks, and the eventual relief as the operation concluded successfully.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. ingrained [ɪnˈɡreɪnd] - (adj.) - Firmly fixed or established, difficult to change or remove. - Synonyms: (deep-rooted, entrenched, fixed)

He introduced fear and ingrained the threat of terrorism into the daily lives of anyone who lives in a big city.

2. circumstantial [ˌsɜːrkəmˈstæntʃəl] - (adj.) - Based on information or circumstances that suggest something is true but do not definitely prove it. - Synonyms: (indirect, conjectural, inferential)

This was circumstantial evidence that he was going to be there.

3. geopolitically [ˌdʒiːəʊpəˈlɪtɪkli] - (adv.) - In a manner relating to the politics, especially international relations, as influenced by geographical factors. - Synonyms: (geostrategically, diplomatically, politically)

So there were risks involved geopolitically in making the decision.

4. ascetic [əˈsɛtɪk] - (adj.) - Characterized by severe self-discipline and abstention from all forms of indulgence, typically for religious reasons. - Synonyms: (austere, abstinent, self-denying)

I think the image that bin Laden had tried to promote was that he was an ascetic living in a cave.

5. meticulously [məˈtɪkjələsli] - (adv.) - In a manner showing great attention to detail; very thoroughly. - Synonyms: (carefully, precisely, thoroughly)

The CIA continued to build the case meticulously over the course of several months.

6. collateral [kəˈlætərəl] - (adj.) - Additional but subordinate; secondary. - Synonyms: (supplementary, subsidiary, ancillary)

We thought that it was important for us not only to protect the lives of our guys, but also to try to minimize collateral damage in the region.

7. duplicity [duːˈplɪsɪti] - (n.) - Deceitfulness; double-dealing. - Synonyms: (deceit, deception, double-dealing)

Pakistan's incompetence or duplicity in failing to locate bin Laden has already sparked a debate.

8. incompetence [ɪnˈkɒmpɪtəns] - (n.) - Inability to do something successfully; ineptitude. - Synonyms: (ineptitude, unskillfulness, ineffectiveness)

Pakistan's incompetence or duplicity in failing to locate bin Laden has already sparked a debate.

9. denigrated [ˈdɛnɪˌɡreɪtɪd] - (v.) - Criticized unfairly; disparaged. - Synonyms: (vilified, belittled, devalued)

We've denigrated al Qaeda significantly even before we got bin Laden.

10. footprint [ˈfʊtˌprɪnt] - (n.) - The amount of space something covers or occupies; the extent of something's presence or impact. - Synonyms: (presence, impact, extent)

But we don't need to have a perpetual footprint of the size that we have now.

Killing Osama bin Laden: President Obama's story | 60 Minutes Full Episodes

Whether we like it or not, Osama bin Laden changed America with that September morning in 2001. He introduced fear and ingrained the threat of terrorism into the daily lives of anyone who lives in a big city, travels by air, or enters a federal building. For more than a decade, bin Laden managed to elude the US military and intelligence establishment and taunted three US presidents.

That finally ended last Sunday, and the last thing bin Laden saw was a Navy SEAL in the third floor bedroom of his compound in Pakistan. Tonight, for the first time, we hear the story from President Obama, who spoke with us on Wednesday at the White House. He explains how the plan was prepared and carried out, what was going through his mind as he watched it unfold, and the secrecy leading up to his historic announcement last Sunday night.

Tonight I can report to the American people and to the world that the United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama bin Laden, the leader of al Qaeda. Mister President, was this the most satisfying week of your presidency? Well, it was certainly one of the most satisfying weeks not only for my presidency, but I think for the United States since I've been president. Obviously, bin Laden had been not only a symbol of terrorism, but a mass murderer who had eluded justice for so long, and so many families who had been affected, I think had given up hope. And for us to be able to definitively say we got the man who caused thousands of deaths here in the United States was something that I think all of us were profoundly grateful to be a part of.

Was this, was the decision to launch this attack the most difficult decision that you've made as commander in chief? Certainly won. Every time I send a young men and women into a war theater, that's a tough decision. And whenever you write a letter to a family who's lost a loved one, it's sobering. This was a very difficult decision, in part because the evidence that we had was not absolutely conclusive. This was circumstantial evidence that he was going to be there. Obviously, it entailed enormous risk to the guys that I sent in there. But ultimately I had so much confidence in the capacity of our guys to carry out the mission that I felt that the risks were outweighed by the potential benefit of us finally getting our men.

How much of it was gut instinct? The thing about gut instinct is if it works, then you think, boy, I had good instincts. If it doesn't, then you're going to be running back in your mind all the things that told you maybe you shouldn't have done it. Obviously I had enough of an instinct that we could be right, that it was worth knowing.

When the CIA first brought this information to you. Right. What was your reaction? Was there a sense of excitement? Did this look promising from the very beginning? It did look promising from the beginning. Keep in mind that obviously, when I was still campaigning for president, I had said that if I ever get a shot at bin Laden, we're going to take it. And I was subject to some criticism at the time because I had said, if it's in Pakistan and we don't have the ability to capture him in any other way, then we're going to go ahead and take the shot. So I felt very strongly that there was a strategic imperative for us to go after him.

Shortly after I got into office, I brought Leon Panetta privately into the Oval Office, and I said to him, we need to redouble our efforts in hunting bin Laden down, and I want us to start putting more resources, more focus, and more urgency into that mission. So by the time they came to me, they had worked up an image of the compound where it was, and the factors that led them to conclude that this was the best evidence that we had regarding bin Laden's whereabouts since Tora Bora. But we didn't have a photograph of bin Laden in that building. There was no direct evidence of his presence. And so the CIA continued to build the case meticulously over the course of several months. What I told them when they first came to me with this evidence was, even as you guys are building a stronger intelligence case, let's also start building an action plan to figure out if, in fact, we make a decision that this is him or we've got a good chance that we've got him, how are we going to deal with him?

When was that, when you set that plan in motion? Well, they first came to me in August of last year with evidence of the compound, and they said that they had more work to do on it. But at that point, they had enough that they felt that it was appropriate for us to start doing some planning. And so from that point on, we started looking at what our options might be.

The vigorous planning did not begin until early this year. And obviously, over the last two months, it's been very intensive, in which not only did an action plan get developed, but our guys actually started practicing being able to execute. How actively were you involved in that process? About as active as any project that I've been involved with since I've been president. Obviously, we have extraordinary guys. Our special forces are the best of the best and so I was not involved in designing the initial plan. But each iteration of that plan, they'd bring back to me make a full presentation. We would ask questions. We had multiple meetings in the situation room in which we would map out, and we would actually have a model of the compound and discuss how this operation might proceed and what various options there were, because there was more than one way in which we might go about this.

And in some ways, sending in choppers and actually putting our guys on the ground entailed some greater risks than some other options. I thought it was important, though, for us to be able to say that we definitely got the guy. It was important for us to be able to exploit potential information that was on the ground in the compound if it did turn out to be him. We thought that it was important for us not only to protect the lives of our guys, but also to try to minimize collateral damage in the region, because this was in a residential neighborhood. I mean, one of the ironies of this is, I think, the image that bin Laden had tried to promote was that he was an ascetic living in a cave. This guy was living in a million dollar compound in a residential neighborhood.

Were you surprised when they came to you with this compound right in the middle of sort of the military center of Pakistan? There had been discussions that this guy might be hiding in plain sight. And we knew that some al Qaeda operatives, high level targets, basically just blended into the crowd like this. I think we were surprised when we learned that this compound had been there for five or six years and that it was in an area in which you would think that potentially he would attract some attention. So, yes, the answer is that we were surprised that he could maintain a compound like that for that long without there being a tip off.

Do you believe it was built for him? We are still investigating that. But what is clear is that the elements of the compound were structured so that nobody could see him. There were no sight lines that would enable somebody walking by or somebody in an adjoining building to see him. So it was clearly designed to make sure that bin Laden was protected from public view. Do you have any idea how long he was there? We know he was there at least five years. Five years. Did he move out of that compound? That we don't know yet. But we know that for five to six years this compound was there. And our belief is that he was there during that time.

This was your decision, whether to proceed or not. And how to proceed. What was the most difficult part of that decision? The most difficult part is always the fact that you're sending guys into harm's way, and there are a lot of things that could go wrong. I mean, there are a lot of moving parts here. So my biggest concern was, if I'm sending those guys in and Murphy's law applies and something happens, can we still get our guys out? So that's point number one. These guys are going in in the darkest of night, and they don't know what they're going to find there. They don't know if the building is rigged. They don't know if there are explosives that are triggered by a particular door opening. So huge risks that these guys are taking. And so my number one concern was, if I send them in, can I get them out?

Point number two was as outstanding a job as our intelligence teams did, and I cannot praise them enough, did an extraordinary job with just the slenderest of bits of information to piece this all together. At the end of the day, this was still a 55 45 situation. I mean, we could not say definitively that bin Laden was there. Had he not been there, then there would have been some significant consequences. Obviously, we're going into the sovereign territory of another country and landing helicopters and conducting a military operation. And so if it turns out that it's a wealthy prince from Dubai who's in this compound and we've sent special forces in, we've got problems. So there were risks involved geopolitically in making the decision. But my number one concern was, can our guys get in and get out safely? The fact that our special forces have become so good, these guys perform at levels that 2030 years ago would not have happened, I think finally gave me the confidence to say, let's go ahead.

I mean, it's been reported that there was some resistance from advisors and planners who disagreed with the commando raid approach. Was it difficult for you to overcome that? One of the things that we've done here is to build a team that is collegial and where everybody speaks their mind, and there's not a lot of sniping or backbiting after the fact. And what I've tried to do is make sure that every time I sit down in the situation room, every one of my advisors around there knows I expect them to give me their best assessments. And so the fact that there were some who voiced doubts about this approach was invaluable because it meant the plan was sharper. It meant that we had thought through all of our options. It meant that when I finally did make the decision, I was making it based on the very best information. It wasn't as if any of the folks who were voicing doubts were voicing something that I wasn't already running through in my own head.

How much did some of the past failures, like the Iran hostage rescue attempt, how did that weigh in you? I mean, was that a factor? Absolutely. Absolutely. No. I mean, you think about Black Hawk down, you think about what happened with the Iranian rescue. And I am very sympathetic to the situation for other presidents where you make a decision, you're making your best call, your best shot, and something goes wrong because these are tough, complicated operations. And. Yeah, absolutely. The day before, I was thinking about this quite a bit. I mean, it would seem to me that it sounds like you made a decision that you could accept failure. You weren't, you didn't want failure. But after looking at all the, the 55 45 thing that you mentioned, you must have at some point concluded that it was, that the advantages outweighed the risks. I concluded that it was worth it. And the reason I concluded it was worth it was that we have devoted enormous blood and treasure in fighting back against al Qaeda ever since 2001.

And I said to myself that if we have a good chance of not completely defeating but badly disabling al Qaeda, then it was worth both the political risks as well as the risks to our men. Bill, after you made the decision to go ahead, you had like this incredible weekend, you surveyed the tornado damage in Alabama, you took your family to the shuttle launch, and this was all going on. I mean, you knew what was going to happen. Yeah, I made the decision Thursday night, informed my team Friday morning, and then we flew off to look at the tornado damage to go to Cape Canaveral. Congratulations. To make a speech, a commencement speech, and then we had the White House correspondents dinner on Saturday night. The presidency requires you to do more than one thing at a time. This was in the back of my mind weekend.

Just the back, middle front. Was it hard keeping your focus? Yes. Yeah. Did you have to suppress the urge to tell someone? Did you want to tell somebody? Did you want to tell Michelle? Did you tell Michelle? You know, one of the great successes of this operation was that we were able to keep this thing secret. And it's a testimony to how seriously everybody took this operation and the understanding that any leak could end up not only compromising the mission, but killing some of the guys that we were sending in there. And so very few people in the White House knew, the vast majority of my most senior aides did not know that we were doing this. You know, there were times where you wanted to go around and talk this through with some more folks, and that just wasn't an option. And during the course of the weekend, there was no doubt that this was weighing on me.

When we come back, President Obama relives the tension filled moments as he and his closest advisors monitored the assault on the bin Laden compound last Sunday. As the final preparations for the raid were underway, President Obama continued with his charade of business as usual. Most people in the White House, including some of his closest aides, had no idea what was about to happen. To break the tension and to clear his head, he played some golf in the morning, waiting for the sun to go down in Pakistan. Then he returned to the White House for the most critical 40 minutes of his presidency. In mid afternoon, he gathered the architects of the mission in a windowless room in the White House basement to watch it all unfold.

I want to go to the situation room. Yeah. What was the mood? Tense. People talking. Yeah. But doing a lot of listening as well, because we were able to monitor the situation in real time, getting reports back from Bill McRaven, the head of our special forces operations, as well as Leon Panetta. There were big chunks of time in which all we were doing was just waiting. And it was the longest 40 minutes of my life, with the possible exception of when Sasha got meningitis when she was three months old, and I was waiting for the doctor to tell me that she was all right. It was a very tense situation.

Were you nervous? Yes. What could you see? We were monitoring the situation, and we knew, as the events unfolded what was happening in and around the compound. But we could not get information clearly about what was happening inside the compound. Right. And that went on for a long time. Could you hear gunfire? We had a sense of when gunfire and explosions took place. Flashes. Yeah. And we also knew when one of the helicopters went down in a way that wasn't according to planned. And as you might imagine, that made us more tense.

So it got off to a bad start? Well, it did not go exactly according to plan, but this is exactly where all the work that had been done, anticipating what might go wrong, made a huge difference. There was a backup plan. There was a backup plan. You had to blow up some walls. We had to blow up some walls. When was the first indication that you had found the right place, that bin Laden was in there? There was a point before folks had left, before we had gotten everybody back on the helicopter and were flying back to base where they said, Geronimo has been killed. And Geronimo was the codename for bin Laden. And now, obviously, at that point, these guys were operating in the dark with all kinds of stuff going on.

So everybody was cautious, but at that point, cautiously optimistic. What was your reaction when you heard those words? I was relieved, and I wanted to make sure those guys got over the Pakistan border and landed safely. And I think deeply proud and deeply satisfied of my team. When did you start to feel comfortable that bin Laden had been killed? When they landed. We had very strong confirmation at that point that it was him. Photographs had been taken. Facial analysis indicated that, in fact, it was him. We hadn't yet done DNA testing, but at that point we were 95% sure. Did you see the pictures? Yes. What was your reaction when you saw them? It was him. Why haven't you released them?

You know, we discuss this internally. Keep in mind that we are absolutely certain this was him. We've done DNA sampling and testing, and so there is no doubt that we killed Osama bin Laden. It is important for us to make sure that very graphic photos of somebody who was shot in the head are nothing floating around as an incitement to additional violence, as a propaganda tool. That's not who we are. We don't trot out this stuff as trophies. The fact of the matter is, this was somebody who was deserving of the justice that he received. And I think Americans and people around the world are glad that he's gone, but we don't need to spike the football.

And I think that given the graphic nature of these photos, it would create some national security risk. And I've discussed this with Bob Gates and Hillary Clinton and my intelligence teams, and they all agree. There are people in Pakistan, for example, who say, look, this is all alive. This is another American trick. Osama is not dead. There's no doubt that bin Laden is dead. Certainly there's no doubt among al Qaeda members that he's dead. And so we don't think that a photograph in and of itself is going to make any difference. There are going to be some folks who deny it. The fact of the matter is, you will not see bin Laden walking on this earth again.

Was it your decision to bury him at sea? It was a joint decision. We thought it was important to think through ahead of time how we would dispose of the body if he were killed in the compound. And I think that what we tried to do was consulting with experts in Islamic law and ritual to find something that was appropriate, that was respectful of the body. Frankly, we took more care on this than obviously bin Laden took. When he killed 3000 people. He didn't have much regard for how they were treated and desecrated. But that again is something that makes us different.

When the mission was over and you walked out of the Situation Room, what did you do? What was the first thing you did? You know, I think I walked up with my team and I just said, we got him. Good job. The White House released video that captured the mood his aides and congressional leaders were given the news. The reason I'm calling is to tell you we killed. And the president thanked cabinet members and advisors after Sunday night's speech. Good job national security team. Thank you. Yeah, proud of you. Your guests did a great job. They did.

It was a moment of great pride for me to see our capacity as a nation to execute something this difficult. This will in a moment President Obama talks about our allies in Pakistan, why he chose not to tell them about the mission and where we go from here now that bin Laden is dead. The special forces mission that killed Osama bin Laden was extremely difficult, not just because of its operational complexity and the uncertainty of the intelligence. It was also complicated by the location where bin Laden was finally discovered, not far from Pakistans capital and right under the noses of the Pakistani army. There have long been doubts about the commitment and trustworthiness of Americas chief ally in the fight against al Qaeda. And Pakistan was kept in the dark about the assault against bin Laden.

Now the relationship between the two countries has never been worse. You didn't tell anybody in the Pakistani government or the military or the intelligence community? No. Because you didn't trust them? As I said, I didn't tell most people here in the White House. I didn't tell my own family. It was that important for us to maintain operational security. But you were carrying out this operation in Pakistan. Yeah. You didn't trust them. If I'm not revealing to some of my closest aides what we're doing, then I sure as heck am not going to be revealing it to folks who I dont know right now. Its certainly the location of his house.

The location of the compound just raises all sorts of questions. Do you believe people in the Pakistani government, Pakistani intelligence agencies, knew that bin Laden was living there? We think that there had to be some sort of support network for bin Laden inside of Pakistan, but we don't know who or what that support network was. We don't know whether there might have been some people inside of government, people outside of government, and that's something that we have to investigate. And more importantly the Pakistani government has to investigate. And we've already communicated to them and they have indicated they have a profound interest in finding out what kinds of support networks bin Laden might have had. A. But these are questions that we're not going to be able to answer. Three or four days after the event.

Pakistan's incompetence or duplicity in failing to locate bin Laden has already sparked a debate over whether the US should continue to supply the country with billions of dollars in military aid. But good relations with Pakistan are still vital to us interests. Most of the supplies for us troops fighting in Afghanistan must move through Pakistan, and President Obama says it remains a valuable source of information. When you announced that bin Laden had been killed last Sunday, you said our counterterrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden in the compound where he was hiding. Can you be more specific on that? And how much help did Pakistan actually provide in getting rid of bin Laden? What I can say is that Pakistan, since 911, has been a strong counterterrorism partner with us. There have been times where we've had disagreements.

There have been times where we wanted to push harder. And for various concerns, they might have hesitated. And those differences are real, and they'll continue. The fact of the matter is that we've been able to kill more terrorists on Pakistani soil than just about anyplace else. We could not have done that without Pakistani cooperation. And I think that this will be an important moment in which Pakistan and the United States gets together and says, all right, we've gotten bin Laden, but we've got more work to do. And are there ways for us to work more effectively together than we have in the past? And that's going to be important for our national security.

But the US won't have to rely exclusively on Pakistan to investigate bin Laden's support network inside that country. The US has had bin Laden's compound under surveillance for months, checking the comings and goings. And there is all that material that was confiscated from his lair during the raid. This video, released over the weekend, shows bin Laden watching himself on Al Jazeera, a novelty item compared to the documents, files and computer drives that are expected to yield valuable information about his contacts in Pakistan and around the world. It's going to take some time for us to be able to exploit the intelligence that we were able to gather on site. And I just want the American people to think about this. These guys, our guys go in, in the dead of night, it's pitch black. They're taking out walls, false doors, getting shot at.

They kill bin Laden and they have the presence of mind to still gather up a whole bunch of bin Laden's material, which will be a treasure trove of information that could serve us very well in the weeks and months to come. It's just an indication of the extraordinary work that they did. Do you have any sense of what they found there? We are now obviously putting everything we've got into analyzing and evaluating all that information. But we anticipate that it can give us leads to other terrorists that we've been looking for for a long time, other high value targets, but also can give us a better sense of existing plots that might have been there, how they operated and their methods of communicating. And we now have the opportunity, we're not done yet, but we've got the opportunity, I think, to really finally defeat at least al Qaeda in that border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan. That doesn't mean that we will defeat terrorism.

It doesn't mean that al Qaeda hasn't metastasized to other parts of the world where we've got to address operatives there. But it does mean we've got a chance to, I think, really deliver a fatal blow to this organization if we follow through aggressively in the months to come. By the time President Obama arrived in New York City on Thursday to honor the nearly 3000 people killed on 911, there were already reports of evidence collected from bin Laden's compound about al Qaeda's aspirations to conduct attacks on us rail systems. This was President Obama's first visit to ground zero since taking office. And he wanted to close a loop. He laid a wreath of red, white and blue at the foot of a tree that was pulled from the rubble, nursed back to health and replanted. And he met with relatives of the victims, one of them, 14 year old Peyton Wohl, who had sent the president a letter earlier in the week about her father, Glenn, who was killed when the towers fell.

She'd spoken to her dad when she was four years old, before the towers collapsed. He was. He was in the building. And she described what it had been like for the last ten years growing up, always having the sound of her father's voice and thinking that she'd never see him again, and watching her mother weep on the phone. Let's go, guys. Come on. The president also paid a visit to engine 54, ladder four, the New York firehouse that had 15 people killed on September 11. He dedicated the raid to them and thousands of others who had lost their lives that day. After the ceremony, we managed to grab a few more minutes with the president to talk about the future.

In some ways, this is the end of a chapter, and I want to ask you a little bit about where we go from here. There are people in Congress, influential people now on both sides of the aisle who are saying that this is an opportunity for us to cut our commitment in Afghanistan and hasten our withdrawals. What's your response to that? Well, first of all, remember that when I came in, I said, we're going to end the war in Iraq so that we can refocus attention on Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the border region there where al Qaeda was focused. We've now removed 100,000 troops from Iraq. We did increase our troop levels in Afghanistan so that we could blunt the momentum of the Taliban and create platforms that would allow us to go after al Qaeda.

We've denigrated al Qaeda significantly even before we got bin Laden. And I think it's important for everybody to understand that the work that's been done in Afghanistan helped to prepare us for being able to take bin Laden out. Now, I've already committed to a transition starting in July where we're going to begin drawing down our troops in Afghanistan. But it's important to understand that our, our job's not yet finished and that we've got to make sure that we leave an Afghanistan that can secure itself, that does not again become a safe haven for terrorist activity. But I think that that can be accomplished on the timeline that I've already set out. I mean, you seem to think that it might hasten our withdrawal.

Mister. Well, keep in mind what has happened on Sunday, I think, reconfirms that we can focus on al Qaeda, focus on the threats to our homeland, train Afghans in a way that allows them to stabilize their country. But we don't need to have a perpetual footprint of the size that we have now. Do you think this improves the chances for some kind of a negotiated settlement in Afghanistan? I think what it does is it sends a signal to those who might have been affiliated with terrorist organizations that might have had a favorable view towards al Qaeda that they're going to be on the losing side of this proposition. And it may make some of those local power brokers, those local Taliban leaders, have second thoughts and say, maybe it makes more sense for us to figure out how to participate in a political process as opposed to engaging in a war with folks who I think we've shown don't give up.

We wanted to know what kind of awards and decorations the president had in mind for the US special forces who participated in the assault on bin Laden's compound. They'll pretty much get whatever they want. But these guys are so low key, so focused on just doing their job, that, you know, they get embarrassed. I think if they get too much attention. On behalf of all Americans and people around the world, job well done. Job well done.

On Friday, the president got a chance to thank them personally. During a visit to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where the helicopter pilots were based. He reportedly met them behind closed doors, along with the Navy Seals who carried out the assault. It's unlikely you will ever see the faces or learn the names of those who avenged 911 and finally disposed of its mastermind. Their identities are classified and likely to remain so. Is this the first time that you've ever ordered someone killed? Well, keep in mind that, you know, every time I make a decision about launching a missile, every time I make a decision about sending troops into battle, you know, the. I understand that this will result in people being killed.

And it. That is a. That is a sobering fact, but it is one that comes with the job. This is one man. This is somebody who's cast a shadow, who's been cast shadow in this place, in the White House for almost a decade. As nervous as I was about this whole process, the one thing I didn't lose sleep over was the possibility of taking bin Laden out. Justice was done. And I think that anyone who would question that the perpetrator of mass murder on American soil didn't deserve what he got needs to have their head examined.

History, Politics, Leadership, Obama, Global, Terrorism, 60 Minutes