The video tells the story of Sundance Scardino's non-traditional career path, highlighting his early work with an airborne unit and pararescue missions before eventually becoming a firefighter. Sundance shares the intensity and experiences he faced in the military, including the dangers and risks involved, and how these experiences shaped his understanding of human vulnerability. His post-service life involves addressing physical and mental injuries and operating a nonprofit to aid veterans through golf.

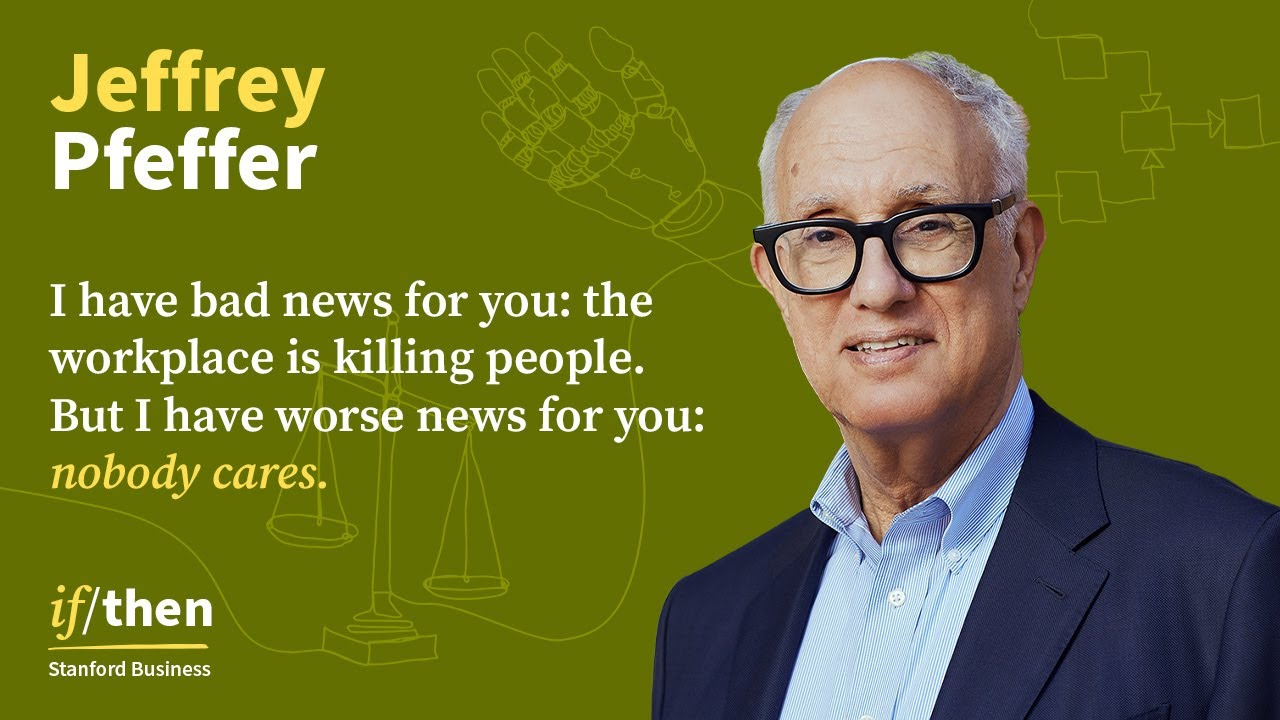

The discussion transitions into a dialogue with Stanford's Professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, exploring how modern workplace stress and practices can be dangerous to health, likening it to risks as significant as smoking. Pfeffer, through his research, argues that these workplace stressors result in substantial health impacts, including possibly being responsible for numerous excess deaths annually. This reflection emphasizes the lack of attention given to workplace stress as a serious health concern and its broad societal implications.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. airborne [ˈerˌbɔrn] - (adj.) - In the air, or carried in the air. - Synonyms: (floating, flying, soaring)

My first job, I worked with an army airborne unit, so I jumped out of planes.

2. pararescue [ˈpærəˌrɛskju] - (n.) - A military unit or personnel trained to conduct rescue operations in dangerous environments. - Synonyms: (rescue squad, emergency unit, search and rescue)

Sundance trained with an outfit called pararescue.

3. ied [aɪ-iː-diː] - (n.) - Improvised explosive device, often used in unconventional warfare. - Synonyms: (bomb, explosive, device)

But most common was an ied blast.

4. pelitors [ˈpɛlɪtərz] - (n.) - Specialized headphones used in combat environments to communicate and block out external noise. - Synonyms: (headphones, headsets, earpieces)

I mean, I've got headphones on. These things are called pelitors.

5. litigation [ˌlɪtɪˈɡeɪʃən] - (n.) - The process of taking legal action or resolving disputes in court. - Synonyms: (lawsuit, legal action, court case)

So we have regulation, litigation, legislation, the three things together.

6. epidemiological [ˌɛpɪˌdiːmiəˈlɒdʒɪkəl] - (adj.) - Relating to the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states in populations. - Synonyms: (medical, statistical, analytical)

We know from separate epidemiological studies going back 40, 50 years that long work hours raises blood pressure systematically and causes all kinds of health issues.

7. steward [ˈstjuːərd] - (n.) - A person or organization responsible for managing or looking after something. - Synonyms: (custodian, administrator, guardian)

You need to be a good steward of the human environment, the social environment as well.

8. overproduce [ˌoʊvərprəˈdus] - (v.) - To produce something in quantities that exceed demand. - Synonyms: (oversupply, overmanufacture, exceed)

So costs were externalized to the broader world. And when you do not pay for the cost of things, economics will teach you, you overproduce it.

9. turnover [ˈtɜːrnoʊvər] - (n.) - The rate at which employees leave a workforce and are replaced. - Synonyms: (attrition, rotation, replacement)

There's a relationship to turnover, which is also costly if you're stressed.

10. sustainable [səˈsteɪnəbl] - (adj.) - Able to be maintained or continued without harming resources or the environment. - Synonyms: (viable, supportable, maintainable)

I have given talks in which what I've said to the executives in the room is as follows, that we are on an unsustainable path.

Is Work Killing Us?

Sundance Scardino didn't choose the usual 9 to 5 career path. My first job, I worked with an army airborne unit, so I jumped out of planes. I did a stack line jumps. Stack line jumps are where you're around 3,000ft to 15,000ft above the ground. And that's how I used to get to work.

Sundance trained with an outfit called pararescue. It's kind of a military emt, but with the training of a Navy seal. We were sent out to pick up people who had done all kinds of stuff. I mean, crashed planes all the way down to. We one time picked up a bomb dog who was severely ill. But most common was an ied blast. We'd fill up both helicopters full of people and start treating them, stopping bleeding and covering up bullet holes, then haul an ass back to the trauma center, sometimes being shot at and drop them off.

For most people, the work would be terrifying. Listen to him talk about his deployment to Afghanistan in 2013. It just was overwhelming. There were so many things because it was like the smell of the gunpowder and the sound. I mean, I've got headphones on. These things are called pelitors. And so, you know, I'm shooting and I'm getting details of the rescue mission that we're going on, and my team leader is talking about assignments and what you're doing to authenticate the people that are coming towards you, because there are things that were being set up that were called rescue traps where you could land and it might not be the people that you're supposed to pick up, and they're actually there to harm you. It's part of the job. But it definitely was something that I was like, oh, shit, this isn't training, and this isn't a civilian mission. This is combat where you could get killed if that wasn't enough danger for him.

When Sundance was discharged, he took a job as a firefighter in Los Angeles and then took on more pararescue missions as a second job. But he said he didn't find any of the work scary. It's exciting to do this kind of work. It's exciting to run into a burning building. I mean, I've gotten to the door of the fire and felt for heat and opened the door, and all the smoke and flames comes blowing out. And I just don't remember ever being scared.

But the piece that I learned is that we're not robots. We're not. We're human beings with feelings and a capacity to process. Even though he kept going, despite this danger, the Toll caught up with him. So I have, you know, a neck injury, I have a back injury, I have a shoulder injury, I have a knee injury, I have post traumatic stress, I have sleep apnea. At the time when I didn't know how to deal with it, I had a drinking problem. He eventually retired because of his injuries, and after a lot of physical and mental therapy, he now runs a non profit that helps veterans deal with trauma by playing golf.

If you've spent most of your career in an office like I have, the work Sundance does probably seems too risky. But according to Stanford professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, the modern workplace is also deadly stress. And the practices that I'm talking about in ill health is actually about as strong as a connection between smoking and cancer. That's the focus of today's episode.

This is if Then a podcast from Stanford Graduate School of Business where we examine research findings that can help us navigate the complex issues facing us in business leadership and society. I'm Kevin Kuhl, senior editor at the gsb. I'm Jeffrey Pfeffer. I am the Thomas D D II professor of Organizational Behavior at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford. And I have been at Stanford since 1979. I started when I was three. Well, my first question is going to be based on your book that you did a few years ago called Dying for a Paycheck, Correct? Now that's a very provocative and interesting title.

Is the problem really that serious? Are people's jobs killing them? Yes. The short answer is yes. Two colleagues, Stefanos Zinios, who is on, as you know, the business school faculty, and Joel Goh, who at the time was a doctoral student and is now at the National University of Singapore. And I did a study in which we tried to estimate the aggregate effect of a bunch of workplace exposures or workplace stressors on employee health. And those stressors include economic insecurity through layoffs. Those stressors include long work hours. Those stressors include an absence of control over what you do and how and when you do it. It's called job control. Those stressors include work, family conflict.

We know that stress is a health risk. We know from separate epidemiological studies going back 40, 50 years that long work hours raises blood pressure systematically and causes all kinds of health issues. We know that the absence of job control experience is stressful. And so what Stefanos, Joel and I did was do an aggregate estimate. If you added all these up, what is the health impact? 120,000 excess deaths per year. 120,000. 120,000 excess deaths annually, which would make the workplace, in aggregate, a higher cause of death than Alzheimer's or kidney disease. So, yes, the workplace is killing people.

It kills people in two ways. First, when you are stressed, when you are under pressure, when you are depressed. And stress and depression are separate constructs, but are empirically correlated. When you are stressed and or depressed, you are going to be more likely to drink, you are more likely to overeat, you are more likely to not take good care of yourself. If you are a smoker, you are more likely to smoke more. So one effect of stress and depression is to cause unhealthy behaviors.

But there is now a growing literature in the medical field which shows that stress and depression affects the central nervous system in ways that cause hormones, cortisol, and a bunch of other things to be out of balance. So there's a physiological effect as well as an effect through behavior of stress and depression on health.

So let me ask you a different question, almost more as a thought exercise. So I have someone close to me whose son has started out in an industry that requires him to work 80, 90, 100 hours a week regularly, six days a week, sometimes seven days a week, sometimes eight days a week, like the Beatles do, sometimes eight days a week. He accepts that because the financial compensation is significant and he's willing. The competition for the role that he's in is fierce.

So when we talk about workplace stress or jobs that are literally killing people, where does the responsibility of the employee and the responsibility of the employer begins? So I believe in the words of Bob Chapman, who wrote a book called Everybody Matters, and he is the CEO of a manufacturing conglomerate called Barry Wehmiller, which is private. He says, and this is completely true, that when an employee comes to work for an organization, when they show up in the morning, they have entrusted their psychological and their physiological well being because the two are connected to that employer.

And the employer then can be a good steward of the human beings whose lives have been entrusted to them or not. If I said to you as a company, you should be a good steward of the physical resources entrusted to you, the air, the water, the carbon, you should recycle. You should do a bunch of things around being a good steward of the physical environment. You would say, of course, you need to be a good steward of the human environment, the social environment as well.

So I believe employers have a responsibility. Are they solely responsible for people's choices and decisions and what they do? Of course not. But the fact that they are not responsible or in control of everything does not mean that they can wash their hands and say, I'm in control of nothing.

So are there structural changes that need to happen? Is it a culture change? How do we remedy the problem, broadly speaking? Well, many listeners are not going to like what I'm about to say. 40, 50, 60 years ago, 70 years ago, it was common for organizations to dump their waste into the air or into the water or. Or into the ground or some combination. And there was a sense in which there was going to be no consequences for that. So costs were externalized to the broader world. And when you do not pay for the cost of things, economics will teach you, you overproduce it.

So we overproduce pollution because nobody had to pay the cost. I was just dumping it out into the world. And some time ago we decided that that was unacceptable behavior. And so we have regulation, litigation, legislation, the three things together. We have legislated regulations and we have litigation, which has cleaned up the environment. The waterways are cleaner, the wetlands are taken better care of. There is more recycling.

We're going to need exactly the same thing. If we wait for employers to do this voluntarily, even though they should, for reasons which we can talk about in a second, they won't. It is going to require legislation, litigation, regulation.

French Telecom, now called Orange, laid off people. France, of course, is different than the United States. When a bunch of those people committed suicide France, the French court system, tried the CEO and the head of HR and convicted them.

The connection between workplace stress and the practices that I'm talking about in ill health is actually about as strong as a connection between smoking and cancer. And so I'm waiting for some district attorney to arrest some CEO for basically murder, because that's what's going on.

But absent that, I don't see much voluntary action, even though it is common sense. And by the way, there's a ton of data to support the following. If you are stressed and depressed, you are more likely to be absent from work, imposing a cost on the employer. If you are stressed and depressed by your job, you are more likely to quit. There's a relationship to turnover, which is also costly if you're stressed. If I said to you we're going to stress and depress you and then expect you to do your best work, of course not. So there are studies that demonstrate the effect of stress and depression on productivity. So through productivity absence, turnover, we are not benefiting the employers by doing this thing. So it's also bad business, in addition to very bad business, abdicating the responsibility as you Put it to employees, it's just bad business.

Correct. Why don't people know this? Or do they know it and willfully dismiss it? Everybody knows it. So as I was writing Dying for a Paycheck, I gave a talk to the Human Resources association in New Zealand, of all places. My first talk on this subject. And I said, I have bad news for you. The workplace is killing people. But I have worse news for you. Nobody cares. And that is still true. Basically, fundamentally, nobody cares.

We don't care because we believe you are responsible. You can take a job or not, right? Yes. Yes. Like you're the son of your friend has made a conscious choice to be in a place where they are being overworked.

So if we think about workplace stress in the popular imagination or how a typical person would evaluate this, it probably isn't something that is top of mind when someone think about health risks. Right. You made the connection between smoking and cancer. Well, for a long time, the tobacco industry first of all denied the science, but I think even in the population, I mean, there were ads with doctors smoking their favorite cigarettes. It took decades for that to sort of change, both in terms of the industry, the regulation, and the popular sort of acceptance of it.

Is there some analog to that in the workplace where essentially overworking becomes something that is frowned upon rather than what is often the case now, I would say, where you're almost considered a slacker if you're not working the longer hours? That seems to be accepted or maybe even encouraged implicitly.

So I think there, I think there are two elements to answering that question. I think the first element is to understand that the reason why there's no smoking on airplanes or in restaurants is because it had been regulated out of existence. And I, you know, this was not a voluntary thing where people voluntarily decided to stop smoking on airplanes. This was a. This was a regulation that goes back to what we talked about because secondhand smoke was deemed to be harmful. I think there's a regulatory component to the changes around smoking, in part because, yes, innocent people were being harmed, in part also because there was an enormous social and medical cost from all of this. So I think that's a piece of the answer.

The other piece of the answer is that smoking became uncool. Hopefully someday overworking your employees will become uncool. We will see. We will wait. Do we need a warning when you take a job? Well, the surgeon general has in fact put out a series of reports on the issue of the workplace and mental health.

There is a phrase now common in the Medical industry, which is called the social determinants of health. We now know that things like poverty affect rates of asthma and health. We know that if you live in a poor neighborhood, you are more likely to be exposed to various forms of environmental pollution of air and water and ground. So we understand there is increasing, not only evidence, but there's increasing acceptance of the idea that health has a social determinant perspective, that this is not genetics and whether or not you eat properly, in a similar fashion, one of the social determinants of health is in fact your workplace and what goes on at your workplace.

Most people spend a significant fraction of their waking hours at work. And work is an important part of our social identity. It is an important source of our income. It is an important source of where we make friends.

I have given talks in which what I've said to the executives in the room is as follows, that we are on an unsustainable path. That health care costs, because when people get sick costs money. Health care costs are on an unsustainable path. They're on an unsustainable path not just in the United States, but in China, in India, everywhere. Because the problems that you and I are talking about are better or worse in some places than others, but they are in fact a worldwide problem.

And so what I tell people is sometime between today and 20, 25 years from today, something is going to be done because we are literally on an unsustainable path. You cannot have ever increasing percentages of GDP going to healthcare, not only in the United States, but around the world. We started a much higher plateau or basis in the United States, but sooner or later we have to address healthcare costs.

And if part of the rise in healthcare costs comes from what is going on to people at the workplace, which causes to go back unhealthy behaviors plus direct effects on their health, we have to fix this. So I want to put this in the context of a real world example. Let's say I'm a manager at a medium to large size organization and I know there are people on my team who are showing signs of stress, maybe they're working longer hours than they used to. Whatever that is, will that employee may feel timid or not able to express this to his or her boss.

So if I'm a manager in this situation, what can I do to change this? Well, it depends upon whether or not you are the boss of the boss. I mean, so to some extent this has to come from the senior leadership levels. I mean, if so, Barry Wehmiller is Run by Bob Chapman, who's written a book about this. Patagonia has a commitment to workplace health. This needs to be something from the concern of senior leadership.

By the way, in the United States, almost all large employers are self insured. So if you have unhealthy employees, not only are you more likely to face absence, turnover and lower productivity, your direct healthcare costs are gonna be higher. You're paying for this directly through the fact that you are paying for your employees health care through the health insurance plans that you're offering. So you should be interested in this.

By the way, the parallel to the physical environment is exact. Walmart figured out that if they put solar panels on the flat roofs of their stores was not only good for the environment, it saved them money. That if you cut down your packaging, this is not just good for the environment because we're not creating so much physical waste, but it's actually cheaper.

We figured out with respect to the physical environment that prevention is cheaper than remediation. We figured out that in fact if we are good stewards of the physical environment, it actually saves money. Same thing for the human environment. It's exactly the same. Prevention is cheaper than remediation. It's easier for me to prevent ill health than it is to deal with it once it occurs and it's cheaper. Yeah.

Will the market at some point make this a priority for companies? And I'm thinking in particular about the recent past where following the pandemic, particularly as remote work started to become more of an option and was more accepted by employers, employees pushed back on the notion of working longer hours and work life balance suddenly seemingly became a very important part of their role as an employee. Now as the economy softens, maybe employees start to lose some of their leverage. But are we entering a phase where work life balance, however you want to characterize that employee well being, is going to be something that the market has to listen to.

I think you have described the situation perfectly. Yes, when times were tight, the employment market was extraordinarily tight. We had the great resignation. We had quiet quitting. Quiet quitting, exactly. We had all of that. So I still remember this is some years ago, a woman called me up, a reporter and she said, I'm doing a story. Employers are telling me people are the greatest asset, they're trying to take better care of them. She said, what do you think? I said, well you know, the forecasts are we're heading into recession.

Call me back in six months. I flew from Seattle, Washington on an airlines flight, happened to be in the front of the plane, which I seldom am, sitting next to this guy, we take up a star conversation. I said, who are you? He said, I'm a senior executive. I run airlines operation in the West. And I said, that's interesting.

I said, how are you doing? He said, not well. He said, this is post pandemic. We were having trouble because I can't. I can't staff fundamentally anything adequately. We don't have enough pilots. We don't have enough people at the ground. We don't have anything.

And I said, my presumption is that during the COVID crisis, you laid people off. And he looked at me and said, of course. And I said, did you get rid of any of your airplanes? And he smiled. I said, you understood that at some point the economy was going to come back and you were not going to take all that capital equipment and throw it away, but you took your human capital equipment and threw it away. How did he react to that? He looked at me. This is the problem.

This is the problem. We inventory parts. We do not inventory labor. We've painted a fairly grim picture here of the workplace. I'm curious if there are any positive trends that you see that might counter some of the darker sorts of aspects that we've discussed here.

So people ask me all the time, after I published Dying for a Paycheck, people would say, what should I do? And I'd say, what should I do if I'm in a workplace that is toxic, to use a word. And I'd say to them, if you were in an auditorium or in a meeting room or in a studio and it began filling up with smoke, what would you do? And they'd say, I'd leave. I'd say, there you go. Leave, leave.

What if that isn't an option? What if you're a single parent with two kids and, you know, find a. Find a. Find a job, find, you know, get yourself there. There are better and worse places to work.

To follow up on a point that you made earlier, the current generation of people entering the workforce are in fact different. They have seen their parents and their aunts and uncles work for companies that threw them out and, you know, and caused harm. And so they say, we are not going to be in general as loyal and we are going to take care of ourselves. Which, by the way, companies for. In the United States for 40 years have told people in the Human Resource Manual, you, you are not. We are not responsible for your career. You're responsible for your career. I tell people all the time, you should take that and you should take that statement seriously.

So I think, I think the people are, are trying to understand that the life is finite and that your health is precious and that you need to take responsibility. Just as you would exercise, just as you would worry about your diet, you ought to worry about the place where you work, because your exercise and your diet are not going to be unrelated to the working conditions in which you find yourself. There's a ton of evidence for this.

So maybe eventually, if this generation, as this generation matures into the workplace, there will be a cost to companies who treat employees poorly. I mean, we will eventually do for the human environment the same thing that we've done for the physical environment. And we might eventually treat the dangers of the workplace in the same way we treat smoking and pollution, where we know that it's bad for you and we know that it needs regulation.

So if leaders truly care about their employees well being and their company's long term success, then they need to take seriously the health hazards of the workplace.

LEADERSHIP, EDUCATION, BUSINESS, WORKPLACE STRESS, EMPLOYEE WELLBEING, SUNDANCE SCARDINO, STANFORD GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS