The video explores the immense complexities and evolving dynamics surrounding mega sporting events like the World Cup and the Olympics. These events, while showcasing the peak of human sportsmanship, also involve massive financial and logistical undertakings for host cities and countries. It raises critical questions regarding the economic benefits, such as changes in tourism, employment, and GDP against the backdrop of significant government spending and potential post-event challenges.

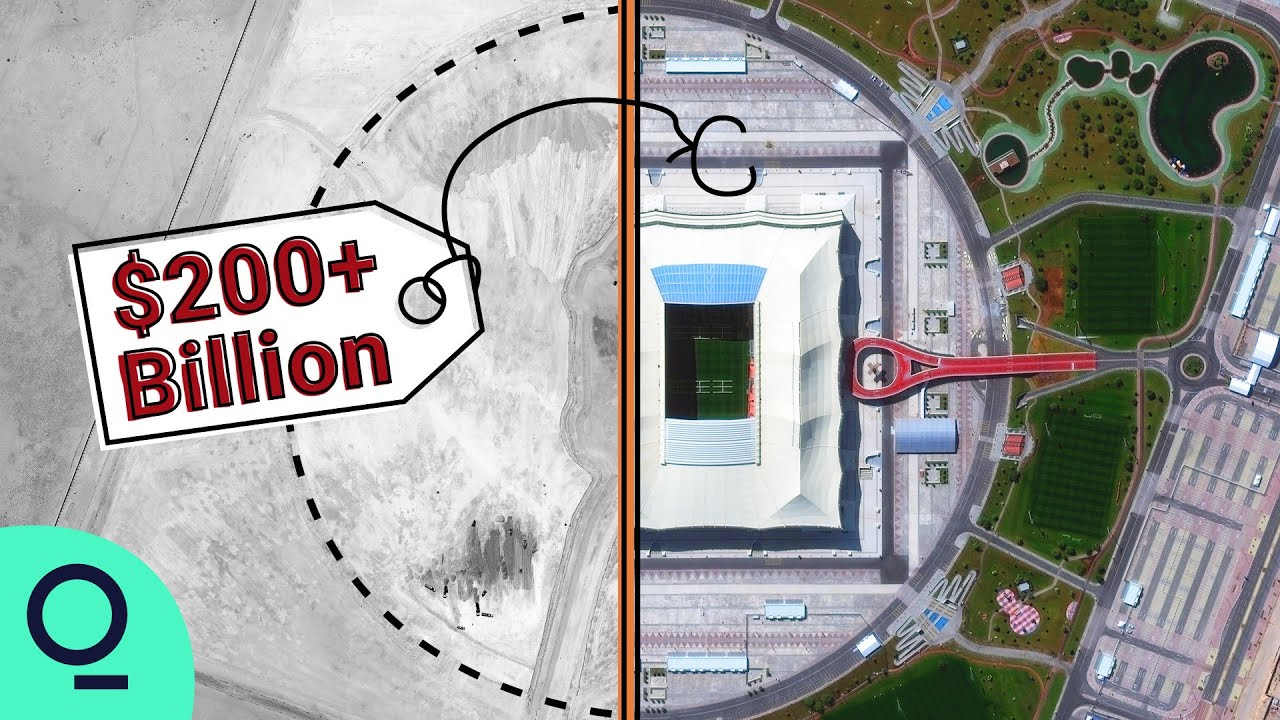

The hosting of the World Cup in Qatar is discussed as a prime example of a nation investing heavily in infrastructure and tourism development in hopes of long-term economic gain. While Qatar expects substantial economic benefits, the event has also been mired in controversy, particularly regarding labor conditions. The video juxtaposes Qatar's investment-heavy strategy with Los Angeles' 1984 Olympic model, which emphasized using existing infrastructure to avoid the crippling costs seen in other host cities.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. mega sporting events [ˈmɛɡə ˈspɔrtɪŋ ɪˈvɛnts] - (noun phrase) - Large-scale sports events that attract global participants and viewers, impacting the host country's economy. - Synonyms: (large-scale events, global sports events)

Every couple of years, mega sporting events like the World cup and the Olympics give us a glimpse into the outer bounds of human performance.

2. calculus [ˈkælkjələs] - (noun) - Complex decision-making process or analysis involving various factors and outcomes. - Synonyms: (analysis, computation, reasoning)

Surrounding that spectacle, quite literally, is an entirely different calculus.

3. infrastructure [ˈɪnfrəˌstrʌktʃər] - (noun) - The basic physical and organizational structures and facilities needed for the operation of a society or enterprise. - Synonyms: (structure, framework, foundation)

But in order to get to that point, the country has spent a massive amount of money over the past decade on infrastructure, including building an entirely new city.

4. lucid [ˈluːsɪd] - (adjective) - Expressed clearly; easy to understand. - Synonyms: (clear, intelligible, understandable)

...to have to fit the community to the games. The first Winter World cup, held in the lucid, affluent state of Qatar, has drawn a massive number of people...

5. optimism bias [ˈɒptɪmɪzm ˈbaɪəs] - (noun phrase) - A belief that tends to overestimate positive outcomes and underestimate negative ones. - Synonyms: (positive thinking, overconfidence, unrealistic optimism)

Well, it's partly due to optimism bias, in which planners simply assume things will cost less than they ultimately do.

6. controversy [ˈkɒntrəvɜːrsi] - (noun) - Disagreement, typically when prolonged, public, and heated. - Synonyms: (dispute, debate, argument)

After years of controversy and criticism, mega sporting events could be on the cusp of a new, more sustainable era.

7. sponsorships [ˈspɒnsərˌʃɪps] - (noun) - Financial support received from a sponsor to pay part or all of the costs involved in staging a sporting or artistic event. - Synonyms: (funding, backing, subsidization)

But beginning in the 1960s, the IOC and local planning committees began to see value in lucrative sponsorships and global television rights.

8. lucrative [ˈluːkrətɪv] - (adjective) - Producing a great deal of profit. - Synonyms: (profitable, rewarding, remunerative)

But beginning in the 1960s, the IOC and local planning committees began to see value in lucrative sponsorships and global television rights.

9. blemished [ˈblɛmɪʃt] - (adjective) - Impaired or spoiled. - Synonyms: (flawed, tarnished, damaged)

In the late 1970s, the IOC was in a similarly desperate position, facing backlash after a series of blemished events earlier in the decade.

10. extravagance [ɪkˈstrævəɡəns] - (noun) - Lack of restraint in spending money or using resources. - Synonyms: (excess, luxury, lavishness)

...there's no input, there's no opportunity for residents to push back against the extravagance of the Games.

Why Qatar's World Cup May Be The Last of Its Kind

Every couple of years, mega sporting events like the World cup and the Olympics give us a glimpse into the outer bounds of human performance. Surrounding that spectacle, quite literally, is an entirely different calculus. The decision to even put on the games in the first place. Once a highly sought role, hosting a mega event is now an entirely different proposition, one that politicians, governments, executives and citizens are asking is it worth it? What is the change in tourism during the games and after the games? Controlling for other variables, what is the change in fiscal revenues? What is the change in employment? What is the change in GDP and so on?

We don't see these gains materializing. There's some big numbers that go around for Qatar's spending on this tournament. I'm worried that the government will be surprised at how many people leave after the event is all over. I can see why hosting the Olympics and bidding on the Olympics is attractive, but it absolutely comes with enormous long-term risks and costs. After years of controversy and criticism, mega sporting events could be on the cusp of a new, more sustainable era. When it comes to organizing the games, there must be a debate, and we've done a lot of reforms over the last decades to make sure that the games remain relevant. But will the changes be enough to convince potential hosts?

One city's example might offer a way forward. We have the ability to really fit the games to our community, as opposed to have to fit the community to the games. The first Winter World cup, held in the compact, affluent state of Qatar, has drawn a massive number of people to the country. Organizers are expecting some 1.2 million people will come to the country over the course of this month-long event. So you're essentially thinking roughly a 10% increase in population every night in the most busy parts of the tournament.

Qatar is also really interested in developing a tourism economy. They've seen the success of Dubai, and even though this is a much more conservative country, think that they can draw people here for other major sporting events, for conferences, just to visit on stopovers to other places. So they're hoping that some of the new hotels and new entertainment venues and the like that they've built for the World cup can get used by the next generation of tourists. Authorities estimate that hosting the World cup could add as much as $17 billion into its economy. But in order to get to that point, the country has spent a massive amount of money over the past decade on infrastructure, including building an entirely new city.

There are various estimates of how much exactly Qatar has spent in order to prepare for this event. The stadiums are really just a small fraction, while costs for the 2022 World cup are reportedly the highest ever for a sporting competition. It's part of an unsettling trend for what are known as mega events. Mega means big. Other than the day-to-day leagues, the NBA, the NFL, MLB, NHL or the English Premier League, the day-to-day leagues where they have every couple of days, or if it's baseball, every single day they have a new game. That's standard economic issues.

But if it's something where a lot of people are coming from out of town and there's one big event, or there's one series of events like the Olympics, is 17 days. World cup has traditionally been around 28 days. You're doing something special that doesn't normally happen and involves tens of thousands, if not millions of people, then we call that a mega event. The first international modern Olympics, in 1896, held in Athens, was considered the first sporting mega event, the largest competition ever held up to that time. Although initially limited to male amateur competitors from only 14 countries, the Olympics have expanded significantly in size, scope and inclusivity since.

One key tradition that has persisted for the past century is that the games travel every four years. Every two years we have the Olympic Games and the Winter Olympic Games, which represent what the movement collectively does and bring the best of the sporting world together. At the helm of the modern games is an organization called the International Olympic Committee, made up of delegates from participating nations. The IOC is responsible for choosing host cities and ensuring that the games are run in accordance with IOC rules.

The movement has evolved tremendously over more than a century. It has gone through many developments as sport, in the end reflects society and to remain relevant. This is a constant adaptation. For the first half century or so, the games were a relatively low budget affair. But beginning in the 1960s, the IOC and local planning committees began to see value in lucrative sponsorships and global television rights. As the potential rewards grew, so did the scale of the events, along with the costs to build infrastructure to host them.

Those costs, however, are not fronted by the IOC. It's up to the host cities who bid for a chance to reap the potential rewards. But is it worth it? Somewhere between four and $6 billion of revenue will get generated by hosting the summer Games in these days. On the expense side, it's much, much, much higher. That's not a good financial balance. Projected costs for an event on an Olympic scale are expectedly high, but the real trouble cities can find themselves facing is when projected costs go substantially over budget, often forcing governments to absorb the overruns.

The University of Oxford in England has done a number of studies on costs and cost overruns. And what they have found is that since 1976, the average cost overrun, or the median cost overrun for the summer Games is 252%. So that means 3.52 times the initial bid. The whole point about these studies is to constantly be aware that organizing an event like this is not a given. It's a constant strive to make sure that the games, when it comes to its economics, do balance what drives costs so exceedingly over budget for mega events?

Well, it's partly due to optimism bias, in which planners simply assume things will cost less than they ultimately do. Promoters might even intentionally distort initial projections to help win over stakeholders. And by the time the mega event rolls around, there's simply no other option but to spend more. If the Olympic Games are going to start on July 20 of a particular year, you can't call up and say, oh, gee, we need another two weeks. The Olympic stadium won't be ready on July 20. No, that can't happen.

And so once you have that kind of a very firm, hard deadline in place, now, the construction companies know that this has to be top priority, and they have to start shifting workers from other construction projects, shifting materials over there, and that gives them an excuse to bid up the prices still more. So you have all of these factors working together, and all of a sudden you're two or three or four or five times higher than the initial bid. Not surprisingly, enthusiasm for hosting the games has varied over the years. For a period, the game seemed cursed, from tragic violence around the 1968 Mexico City and 1972 Munich summer games, to a debt-ridden financial disaster in 1976 that Montreal spent the next 30 years paying off.

More recently, enormous budget overruns, political controversies, and viral scenes of decaying stadiums in Athens, Rio de Janeiro and Beijing have led some citizen activists to openly question the environmental impacts, political optics and cost-benefit ratio of hosting. Boston is an absolutely beautiful city. It looks great in the summertime. It looks great when you envision that helicopter or drone shot looking over a brand new stadium with fireworks going off and our gleaming skyline in the background and the Charles river on one hand and Boston harbor on the other.

It's really an impressive and gorgeous place. It's also on or in the most valuable time zone in the world. The East coast time zone has something like 40 or 50% of all American television viewers. Boston beats out Los Angeles, San Francisco and DC and will be the US bid in a worldwide battle for the 2024 games. The polling was very clear that at first, residents of Greater Boston supported the Boston 2024 Olympic bid.

The idea of the Olympics. Improving the public transportation system in Massachusetts was always the most appealing and enticing part. But what became clear is that over time, the more people learned about the implications of the bid, the risks and the costs, that they got beyond those glossy images and saw what it would really mean for their lives and for the future of the state, that people's support for the games dropped dramatically. We see that the bid requires building the three most expensive Olympic venues that every Olympics since 1960 has gone over budget.

We felt that there needed to be a real debate about whether the Olympics was the right thing for Massachusetts or not. And we saw that because of the power of the people pushing the bid, there were going to be very few institutions that would normally ask tough questions of the bid that were going to do that in this case. And so that opposition had to come from the grassroots. And that's why we formed no Boston Olympics.

Boston 2020 four's original proposal was to put beach volleyball here in Boston Common. Not a place that has sand, not a place along the water, and one of the most historic public spaces and important public spaces in the US. This is the original public park in North America. Boston was the first major city to stand up and say no to the summer 2024 games. But in the wake of our decision in Boston, other cities dropped out.

Rome, Italy had been talking about bidding. A new mayor was elected there who said she had more important priorities than the Olympics, and so that bid died. Hamburg, Germany actually had a public referendum to bid on the 2024 games and voted that down in November of 2015. Budapest, Hungary there was a grassroots opposition to the games there that forced the question of the Olympics to be on the ballot, and eventually the organizers of the games there decided not to move forward with it.

In 2017, left with a dwindling set of potential hosts for the 2024 games, the International Olympic Committee made an unprecedented move. It awarded the two remaining contenders at the same Paris for 2024 and Los Angeles for 2028, giving the IOC some extra breathing room and a chance to focus on a series of reforms. You have to listen to the critics as well, and we've been in contact with them and other opponents to the games because this is our mission, to listen and to make sure that their analysis, we do understand why they reach these conclusions and what we can improve.

In the late 1970s, the IOC was in a similarly desperate position, facing backlash after a series of blemished events earlier in the decade. Sensing a rare opportunity for leverage, the city of Los Angeles decided that it could make the 1984 Olympics a success, but on its terms. What happened in 84, it was good for Los Angeles, it turned out, for some very interesting reasons, but it was a disaster because the IOC had to give up on many of its requirements.

The IOC requires, for instance, that a host city guarantee that it will carry out all of the tasks in its contract and take full responsibility financially for any costs that are involved. In 1984, because Los Angeles was the only city that was bidding, the IOC basically was on its knees in front of the Los Angeles committee, saying, "please, please do this." And so the Los Angeles committee dictated terms, and one of the terms was, we're not going to be responsible for cost overruns. By most accounts, the 1984 Los Angeles summer games were a resounding success.

Instead of saddling taxpayers with a catastrophic loss, the games were actually profitable, thanks to strategic corporate sponsorships and manageable costs. Because the metropolitan area already had suitable stadiums, venues and housing, very little new construction was needed, preventing the sort of surprise expenses that had plagued earlier host cities. And now, amid another challenging period for the Olympics, Los Angeles is again trying to rewrite the narrative. We like to say that the LA 84 games are actually what gives us the ability to have such great public support here in Los Angeles for the games.

You can't walk around this city and I not meet somebody who has a positive memory of 1984. And that's really the starting place for us. We are a no-build games, and sometimes we like to say it's a part of our radical reuse philosophy around sustainability. The fact is, the best venues are the ones you don't have to build. Right over my shoulder, you can see one of the main pieces that will actually be the secret sauce of LA being able to host the Olympic Games, and that's UCLA.

We have UCLA and USC within really just about 1012 miles of each other. And really, that's the beginning stages of infrastructure. But beyond that, you know, we really have just an extraordinary number of venues here in LA and in greater Southern California, whether it's three facilities, three stadiums that are over 75,000 seats, multiple arenas, different types of facilities, and so we're just tailor-made to be able to actually a mega sporting event like the Olympics and the Paralympics.

As for potential cost overruns, LA 28 has a plan in mind. We actually are carrying a 10% contingency from day one in our budget in terms of how and what it is that we actually think about. And so we're trying to build against that contingency. I think it's incumbent upon all of us to think about everything that we do, and think about it through the lens of sustainability, we'll have probably just shy of 100,000 jobs that will be a part of our journey over the next six years. And that's billions of dollars of economic impact directly to citizens of LA.

Beyond the raw cost benefit figures, there is another value to the Olympics that is harder to measure. For us, it's really about human legacy. And it starts actually with the kids that we want to be sitting in the stadiums thinking and dreaming that they too can be an Olympian or a Paralympian as a part of our Play LA program, which is our $160 million investment into kids in Los Angeles. One of the real important parts of that is we've introduced adaptive sports into the Wrexham park program in the city of LA.

I'm optimistic about the 28 games for the same reasons. I think that they have really excellent management of the organizing committee and they're Los Angeles, they've got a lot more stadiums now than they had back in 1984 and they've got more infrastructure, including public transportation, that they didn't have. So I think it'll turn out well.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, there are places where costs simply aren't a major concern. But this path comes with its own set of problems. The person who really seems to have wanted to host the World cup more than anyone else is Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani. He's now known as the father Emir. He was the former ruler of Qatar and this was really his desire not just to host, you know, a massive football tournament.

He knew that it would drive an enormous amount of development in the country that Qatar really needed to become a kind of modern place. And that's exactly what happened. In the last decade alone, Qatar has built more roads, bicycle paths and bridges than during the entire previous half-century. Funded by a robust petroleum and natural gas-based economy, the government was less concerned with short-term profit and more interested in the long-term benefits of future tourism, business development and global prestige.

For instance, they've gone to great lengths and no doubt to show off cutting edge engineering feats such as this innovative stadium design, constructed partly out of shipping containers meant to be easily deconstructed and transported elsewhere. But the attention the nation has received has generally not been so positive. Behind the scenes, many more are being exploited. Unpaid forced labor, badly treated. It's very hard to give an exact figure. I would suspect it's actually in the hundreds of, I think hundreds of workers have died to make this World cup possible.

There was initially reports about the deaths of workers in stadium projects and other projects directly tied to the World cup. This obviously set off an enormous international outcry, and ultimately, the government did start making reforms in order to respond to this. People were living in very cramped, unsafe, unsanitary accommodations. They've set minimum standards on that. They also introduced a universal minimum wage, meaning it applies to people of all nationalities. It's not much. It's about $274 a month, but it's something.

And in fact, it's the first universal minimum wage across the Gulf region. Generally, activists are not entirely happy with the reforms that Qatari government has made. They don't believe that some of these reforms have gone far enough. On worker deaths, for instance. Nobody really had bothered to count for a long time how many workplace deaths and injuries you had across the country. Activists are very concerned about what happens after everyone goes home. I think these are questions we don't know the answer to.

Qatar's hope is that in the long run, memories of compelling matches will outlast any lingering controversy. The 2022 World cup story echoes other mega events in recent years where strong, centralized governments have spent lavishly to help build global prestige, only to find themselves marred by controversy. If you look, for example, at the 2022 Winter Olympic bidding process, all of the democracies that were bidding in that process actually dropped out before the final bidding phase.

The only two cities that were left were Beijing, China, and Almaty Kazakhstan, both autocratic countries where there is no democracy, there's no input, there's no opportunity for residents to push back against the extravagance of the Games. Russia received a four-year ban for doping from the World Anti Doping Agency. China has been criticized by some countries and human rights groups over what they say is abuse against Uyghur Muslims.

They're going to be under increasing pressures from corporate sponsors. They're creating all sorts of problems in terms of how the labor force is treated, in terms of environmental destruction and so on. So corporations are sort of pulling back, or they're saying, well, if you expect us to stay around, you've got to clean this stuff up. Mounting public concerns from citizens, cities and sponsors over the recent spate of controversial games have forced organizing bodies like FIFA and the IOC to pursue reforms.

One approach to address the sustainability concern has been to spread out mega events over a region or even a continent, instead of forcing a single city to take on the burden. I think FIFA has an easier job only because there are more places that have the necessary venues and infrastructure and because of the very profound and lasting and pervasive popularity of soccer. They have more leeway, I think, than the IOC. So hopefully we'll see some good changes there. In fact, things are already looking differently in the next World cup, which will be spread out in 16 cities across North America and rely mostly on existing infrastructure.

The World cup is coming back to Boston in 2026, and it never crossed our minds to create a no Boston World cup group because the costs are just going to be a small fraction of what hosting the Olympics would have been. As for the Olympics, the IOC has spent the past decade reflecting on its complex legacy and outlining broad new reforms aimed at reinventing the games for the sustainability conscious 21st century. Listen, the most important was a decade ago when we adopted a motto that a city does not adapt to the games, but the games adapt to a city.

Then the second thing which was important is we don't build if it's not absolutely needed. We have a sustainability agenda that is very appealing as well. Will be climate positive as a rule from 2030, but already Paris 2024 will be climate positive, which is a great objective to reach. I think everybody also is recognizing the efforts when it comes to sustainability and the whole agenda, economic, social and environmental. Yes, it's more to deliver for the organizers, but for the better.

The successful Olympics is one that first and foremost brings back to the community what they were expecting. Even the bidding process, once a fierce competition that often encouraged the sort of wild promises that led to financial pitfalls, has been reshaped. It is a partnership now. So we have cities that come to us and say, listen, what does it take if I want to organize the games in 2040? And the big difference is that the IOC is not judging anymore the quality of a given value proposition. It is contributing to it.

The plans for upcoming games, Los Angeles in 2028, Milan in 2030 and Brisbane in 2032, already seem to be heeding the warning signs of the past, so far, at least. But some critics have proposed an even more radical concept. What I would favor in the long run, what I think is most rational, particularly in these days of climate change and the need to conserve resources and not waste resources, is we ought to have one city that hosts the games permanently. Having everyone agree on a single host city might be a challenging diplomatic problem.

Regardless, the institutional reforms within the World cup and the Olympics demonstrate that mega sporting events can respond to the demands of an ever-evolving planet. And the days of massive cost overruns and wasteful infrastructure may be behind us. I think there are much more sensible ways to proceed whether the world decides to be sensible or not, I think is still an undecided question.

Economics, Innovation, Global, Infrastructure, Event Planning, Sustainability, Bloomberg Originals