Eric Mead,

recognized as one of the greatest sleight-of-hand artists in the world, captivated an audience with a presentation that combined magic and insights into human susceptibility to

misinformation. Through engaging magic tricks with a participant named George, Eric demonstrated how easy it is to deceive the senses, thus teaching the audience about the fallibility of sight and sound. He expertly

showcased how certainty is often an illusion, crafted through our experiences and expectations.

Delving deeper, Eric explored the theme of misinformation and its prevalence in today's society. He highlighted how our senses, assumptions, and biases make us susceptible to deceit, even from

technologies like AI tools

that are rapidly advancing. Eric used practical examples to illustrate these

concepts, such as an audio trick that invited the audience to choose what they believed they

heard, thereby showcasing our tendency to hear

what we want.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. sleight of hand [slaɪt əv hænd] - (n.) - Skill and dexterity, especially in deceit or trickery, usually involving manual skill to entertain or deceive audiences. - Synonyms: (magic, illusion, conjuring)

It is my distinct pleasure to introduce Eric Mead, perhaps the greatest sleight of hand artist in the world today.

2. misinformation [ˌmɪs.ɪn.foʊˈmeɪ.ʃən] - (n.) - False or misleading information spread regardless of intent to deceive. - Synonyms: (disinformation, falsehood, untruth)

I want to talk a little bit about the tools that make that possible and how misinformation is absorbed in the brain.

3. tentative [ˈten.tə.tɪv] - (adj.) - Done without confidence; hesitant. - Synonyms: (uncertain, cautious, unsure)

Notice how he's tentative already.

4. deceived [dɪˈsiːvd] - (adj. / v.) - Misled by false appearance or statement; tricked. - Synonyms: (tricked, fooled, misled)

Our senses can be deceived.

5. biases [ˈbaɪ.es.ɪz] - (n.) - Prejudices in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair. - Synonyms: (prejudice, partiality, predisposition)

And the biggest thing that fools us, that allows us to be susceptible to misinformation, are biases.

6. skeptical [ˈskep.tɪ.kəl] - (adj.) - Not easily convinced; having doubts or reservations. - Synonyms: (doubtful, distrustful, questioning)

For a while, we’re going to be mistrustful of digital life.

7. intrinsically [ɪnˈtrɪn.zɪ.kəl.i] - (adv.) - In a way that is fundamentally part of something. - Synonyms: (essentially, inherently, naturally)

I do think it's clear that some people are going to use them in ways that are not for our best interest.

8. vigilance [ˈvɪdʒ.ɪ.ləns] - (n.) - The action or state of keeping careful watch for possible danger or difficulties. - Synonyms: (alertness, attentiveness, surveillance)

No one, no matter how well educated, no matter how smart you are, no matter how on guard you are, everyone is susceptible to being fooled.

9. refraction [rɪˈfræk.ʃən] - (n.) - The bending of a wave when it enters a medium where its speed is different. - Synonyms: (bending, deflection, deviation)

We know about refraction and the fact that light travels slower through water.

10. cartesian [kɑrˈtiːʒən] - (adj.) - Relating to the philosophical and mathematical ideas of René Descartes. - Synonyms: (analytical, logical, methodical)

This is the sort of the cartesian model about trusting your senses as your only source of information.

Is seeing believing? - Illusionist Eric Mead - Nobel Prize Summit 2023

Good morning. I'm Anne Merchant with the creative engagement programs at the national Academies of Sciences. It is my distinct pleasure to introduce Eric Mead, perhaps the greatest sleight of hand artist in the world today. We are so honored to have him on our stage this morning that we have been meeting in secret and hatching a plan to create a special Nobel prize for magic to honor his many accomplishments. Knowing how modest he is, we were certain he would decline such an award had he heard about it in advance. Regardless of how much he clearly deserves it. I am certain you'll all agree after his presentation today that such an award is not only warranted, but long overdue. With that totally inadequate but truthful and sincere introduction. Please join me in welcoming Eric Mead.

Hi. Hi. It's kind of quiet out there. Hi, high. That's good. My name is Eric. That introduction is the second video I made of that. The first one was actually so convincing that I got worried that people would think it was real. And so I made sort of this clownish one. And I want to talk a little bit about the tools that make that possible and how misinformation is absorbed in the brain and how we as people can be fooled. As you heard, I'm a sleight of hand magician. I'm going to begin, I think, with a little bit of magic.

Would that be all right? I need somebody. That's great. The blood pressure in the room just visibly. Somebody who is not afraid to. Just gentleman right here. What's your name? George. George. Do you speak English, George? You have an accent. Yes, I do speak English. I'm English. Oh, you're English. So in truth, it's actually me who does not speak English. I speak American. Would you mind, everybody get a little round of applause and let George make his way up to the stage here.

George, how are you? I'm doing very well, thank you. Thank you very much. English. Okay, great. From England. Yeah, from England. Would you stand just on the other side of this table? And this is George, everybody. Yeah. It is a very brave act to be sitting out there thinking that you're just going to enjoy yourself and then suddenly be thrust into the spotlight. You have a reserved seat. Are you someone that I should know who you are? No, just here to help. Just here to help. But you haven't met me before. No, certainly not. Seem pretty happy about that.

Okay, so here's what we're gonna do. Do you know what that is? Cup. It is, in fact, a cup. Notice how he's tentative already. He's on guard. That's a good thing. It is a cup. You step inside, walk around, make sure there's no trap doors or escapes, escaping gas or anything funny going on there. And then I give the audience a quick peek. And then this. Do you know what this is, George?

A ball. One of many possible correct answers. This is, in fact, a ball. This one is a cat toy. It's a little wooden ball. You can feel it. And it's got, like, a sweater crocheted around the outside. But I don't own cats. But I was told that you soak this in catnip and then you give it to your cat and they chew on it, and they get a little like a kitty. Buzz off the deal. So here's what's going to happen. The ball goes like this, and it hides underneath the cup, okay? And you and I are going to play a guessing game.

I want to be very clear to the audience before we start that I'm going to ask him, under pressure, to guess several things, and sometimes he will get it wrong. This should not reflect poorly on him. You would get it wrong if you were up here, too. I'm a magician. I've done this a lot, and I cheat. So a little ball is hidden underneath the cup. And normally this would be done with three of these, and I would scramble them all around like this. And then you would be asked to guess which cup. Right. This is the simplified version. There's only one cup. It's not quite that simple.

What's going to happen is this. I'm going to take the ball and I'm going to hide it in my pocket. Sometimes. Sometimes? Sometimes I'm going to leave it underneath the little cup. And your job is to guess whether it's in the cup or whether it's in my pocket. It's a 50 50 proposition. We're not playing for money, because, again, I cheat. Sound good? I think so, yes.

You think so? How certain are you where it is right now? 80%. 80%. Where would you say it is? I'd like to think it's in your pocket. Yes. Let's start at the beginning. Here we go. Little ball, little cup. Right. Let's involve some other senses. George, you hear that rattling around? Yes, yes. I'm gonna hold it where you can't quite see. Reach down in there and scoop it out. Yes. Okay. And there's nothing else hiding down there? Drop it back inside.

How certain are you where it is right now? 100%. It is, in fact, in there. Okay. But it gets harder as we go. Where is it right now? Do you have a guess? In the cup. In the cup. Oh, so close. So close. It's not going well, isn't it? No, you're doing great. You're doing exactly what anyone else would do. I know, right? Let me show you something about this game. When I. Because of the special circumstance that we find ourselves in, and we're going to talk openly about misinformation and how we process information, let me show you one aspect of this.

When I take the little ball like this, and I put it in my pocket, it never actually goes in my pocket. Yes, let's see that again. Like this in my pocket. And it's still right here. So when I do this. Hey, you can do cool variations like this. One in one ear, out the other. The sound crew just went insane on that. Sorry, I just whacked right on the microphone. I apologize. Or this is my ten year old daughter's favorite. Oh, come on. A little bit of fun now and then.

Okay, so what happens is, when I take the ball and you're watching to see if I put it in my pocket, right, what's actually going on is I come over and I stand up the cup like this, while you're staring at my pocket, and then you go, hey, it's in your pocket. And I go, okay. It's not as good when you explain it. I understand that. You're sort of soured on the whole deal, aren't you? I'll tell you what, we'll do this. How certain are you where it is right now? 2020. Check this out, George. Whoa.

Say it's a lemon. It's a great big yellow thing. It's large. How does someone take a great big, bright yellow thing and sneak it under the cup and no one sees it happen? George, what's your guess? From the audience, perhaps? From the audience, perhaps? I don't actually know the answer, but it must be the same way I did this one. This is George, ladies and gentlemen. Watch out for that. Thank you very much. Thank you, George. Let him hear you.

So, let's talk for just a minute about why we get fooled, right? Why is it that we get fooled? I've spent my whole life thinking about this subject since I was a little boy. You could call this talk, I guess, you know, defense against the dark arts, if, you know, you're Harry Potter. That was a course taught at Hogwarts, where they learn to sort of defend themselves against black magic and evil. And although I don't think the new sort of AI tools that we're going to discuss for part of today are evil inherently. I do think it's clear that some people are going to use them in ways that are not for our best interest.

So how can we harden our defenses? Well, the first thing is, there are some of you out there that are saying to yourselves, if I had been up there, I would have made different guesses than poor George, and it would have been hard. I would have been counterintuitive. None of that matters. I'm a magician. You would have been wrong, too. Okay. And that's the first thing that I want to say, is everyone is susceptible. No one, no matter how well educated, no matter how smart you are, no matter how on guard you are, everyone is susceptible to being fooled.

And we get fooled all the time. Part of it is that you can't trust your senses. What your eyes tell you, what your ears tell you, what you touch. He was listening to it. He felt it. I could have done it with taste and smell, but it's sort of a weird thing to do in a live performance situation. But our senses can be deceived and therefore certainty. I asked him several times about his certainty. Certainty is an illusion. Everything that you think you're certain about, you should probably start to question, right?

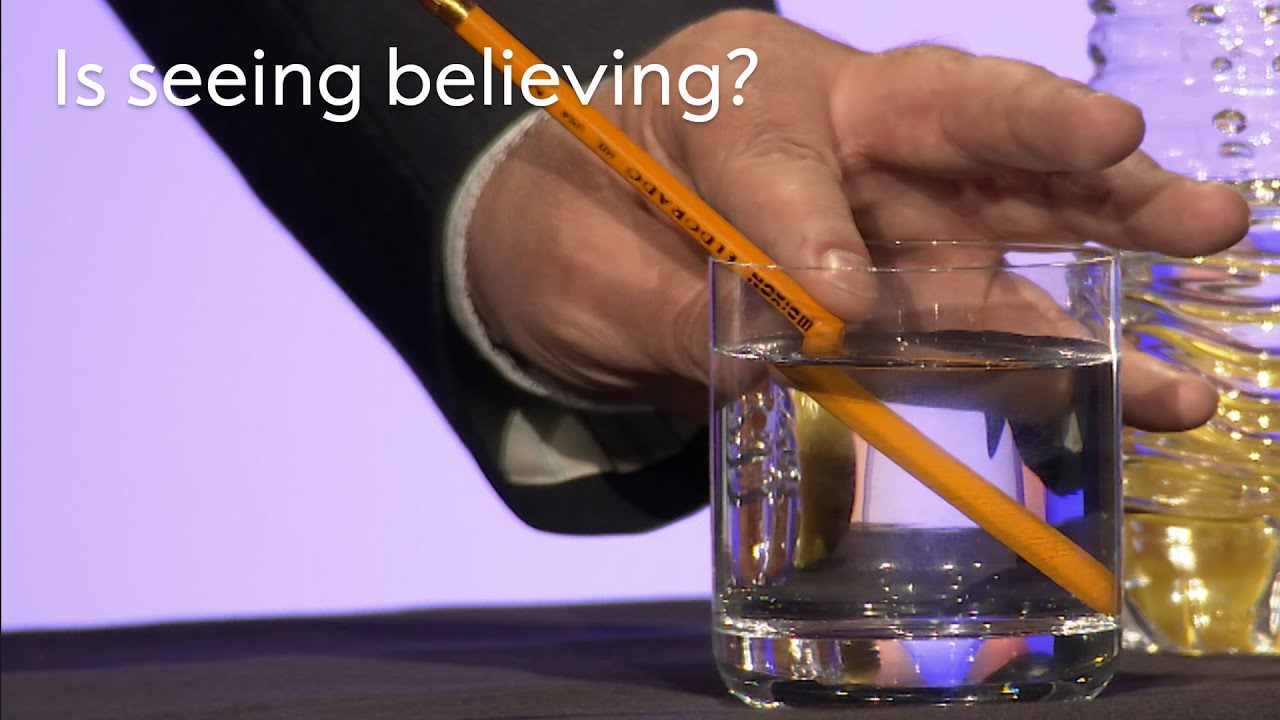

This is the sort of the cartesian model about trusting your senses as your only source of information, right? Rene Descartes took the. Well, I could do it for you. He took the. Like, a glass of water and he put a stick in it. Right? As his example. I have a pencil, but it'll do. Maybe it won't stay in. I'll have to hold it like this. And you can see that maybe. Well, no, you can see that. I can't tell if it's enough in the water that you can see that it looks bent. Yes. Is everyone familiar with this illusion? Right? And so I'm going to hold it like this. And so if you trusted just your eyes, you would say, hey, you know, that is not a straight stick, that is a bent stick.

And then some people go, yes, but we're wise. We don't have to just trust our eyes. We know about refraction and the fact that light travels slower through water than it does through air, and it makes it look bent. And that's when I pull it out and show you this one actually is bent. So your certainty is an illusion, especially when someone is intentionally trying to deceive you. Everyone can be fooled. Certainty is an illusion. We have evolved to be pattern seeking brains. Pattern seeking brains. So much so that we find patterns where they don't exactly exist.

I have a really interesting, I think, demonstration of this, an audio. It's not an illusion. I'm going to ask the sound crew to play something in a second. I have a couple of audio clips. What you're going to hear is a recording of a children's toy, and it has, at first you'll hear sort of a static, like a little white noise background, and then you'll hear a robotic voice say the word brainstorm. One word, two syllables. Brainstorm. Could you play that clip for us? And again, can you, I don't know if you can hear it. Sort of a whispered robotic voice. And it says brainstorm.

Could you play that again for us? Can you hear it? Okay. I had an audio engineer strip the voice out of that and replace it with the. With the same voice, except instead of saying one word, two syllables, I had him replace a two words, three syllables. We're going to hear the same background noise and the same voice, except instead of brainstorm, you're going to hear the voice say green needle. Green needle. Ok. Would you play the second clip for us? Green needle. Green needle. One more time. Green needle.

The second one. Can you hear it? The great philosopher Paul Simon once said that a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest. That really is a voice saying something. But you're not hearing two different clips there. I'm playing the same clip over and over, and what you expect to hear is what you hear. And I'm going to prove it because I've shown people this and they go, that's not true. You're lying to me. So I'm going to have them play it like three more times and you decide for yourself in real time whether you want to hear the word brainstorm or whether you want to hear the words green needle.

And that's what you will hear. Would you just repeat maybe three times that recording for us and decide, and now switch if you'd like, or stay. And again. Right. It's crazy. This is a sort of a mild demonstration of bias. And the biggest thing that fools us, that allows us to be susceptible to misinformation, are bias. Our own biases. Study after study. You know, if something confirms what you already believe, you're more likely to believe it, accept it. If something challenges what you already believe, you're more likely to discard it. I'm suggesting that we need to sort of think about going forward, especially as the new misinformation starts tsunamiing in on us, knowing that we can be fooled, right?

Knowing that your assumptions, your assumptions catch you every time, right? You've had so much experience with the world that when I do this, you know where the ball is, right? You assume that because you've watched people transfer something from one hand to the other a thousand times, you assume that that's what's happening when it's not what's happening. This is why adults are so easy to fool, especially really smart scientists. The best really smart scientists, slightly inebriated, best audience ever. Because, you know, they know they can't be fooled. So they make all the assumptions. The hardest audience ever. Ten year olds. Not enough experience with the world to make assumptions. They just go, it's in your other hand.

So our assumptions, our biases and our experience in the world, and knowing that we can be fooled, that's going to be our main protection. I want to make two final things. I want to end on like a note of hope, right? That's the final sort of truth. Trust, hope. Two things. Number one, we've been here before, right? These new tools, the AI tools that are coming out are hugely powerful and kind of frightening if you're paying attention. But at the turn of the last century, when photography became a thing, everyone thought it was the end of the world. Art was ruined. We could be lied to. And there was a fad religion at the time called spiritualism, where they could talk, talked to the dead, and the darkroom experts started making pictures of ghosts.

And people were like, how are we going to deal with this? Well, we learned to deal with that. The same is true with Photoshop. In the early late nineties and early two thousands, when that became an ubiquitous tool that anyone could use. We thought we can never have photographs in court anymore because we can't trust pictures. And we've learned to deal with that. So I believe that we will learn in the long term to deal with these new tools and to sort of work our way and find our way into using them for our benefit rather than our ruin.

That's number one. I think that in the short term, though, I'm a little worried about what's going to happen with these new tools. And I think there will be a backlash. And for a while, we're going to be mistrustful of digital life sort of in general. And I think that will force sort of a retreat from digital life a little bit and more to people talking to each other face to face, person to person, heart to heart. And for me, that's a very hopeful note to end on. Thank you very, very much.

Magic, Eric Mead, Illusion, Science, Technology, Education, Nobel Prize