The video addresses urgent challenges related to sustainable development, specifically focusing on responsible consumption and production, as outlined in Goal 12 of the United Nations sustainable development Goals. It emphasizes the environmental and social impact of the fashion industry, highlighting how careless systems of production and consumption have led to increased pollution, carbon emissions, and inequality. The speaker challenges the audience to think about the origin of their clothing and the socio-environmental implications of fashion industry practices.

Attention is drawn to the staggering figures of textile waste and carbon emissions created by the fast fashion industry. The speaker discusses the consequences of overproduction and overconsumption, particularly noting how it affects countries in the Global South. Examples from Ghana reveal how second-hand clothing waste is destroying local environments and economies. There is an urgent call for change in both consumer behavior and industry practices, as well as policy development to enforce sustainable practices.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. sustainable development [səˈsteɪnəbəl dɪˈvɛləpmənt] - (noun) - Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. - Synonyms: (sustainability, eco-friendly growth, environmental development)

I'm here to talk about sustainable development.

2. insatiable [ɪnˈseɪʃəbəl] - (adjective) - Impossible to satisfy. - Synonyms: (unquenchable, unappeasable, voracious)

We've created these careless systems of consumption and production to meet not only our basic, basic needs, but our insatiable desires.

3. circular economy [ˈsɜːkjʊlər ɪˈkɒnəmi] - (noun) - An economic system aimed at eliminating waste and the continual use of resources. - Synonyms: (closed-loop economy, regenerative economy, sustainable economy)

The Awe Foundation, a circular economy organization working in Ghana.

4. biophysical [ˌbaɪoʊˈfɪzɪkəl] - (adjective) - Relating to the biological and physical aspects of the environment. - Synonyms: (ecological, environmental, organic)

We need to care not only about ourselves, but about each other and about our entire biophysical worlds.

5. linear system [ˈlɪniər ˈsɪstəm] - (noun) - A system where materials flow in a straight path, from raw materials to production and disposal without consideration for sustainability. - Synonyms: (straight-line system, throwaway system, non-circular system)

We've created a linear system.

6. microfibers [ˈmaɪkroʊˌfaɪbərz] - (noun) - Very small fibers that can detach from clothing materials and pollute the environment. - Synonyms: (microfragments, tiny fibers, small fibers)

They know that their sneakers, which are mostly made out of plastic, are releasing microfibers into the environment.

7. eco design [ˈiːkoʊ dɪˈzaɪn] - (noun) - Design that takes into account the environmental impact of the product throughout its lifecycle. - Synonyms: (green design, sustainable design, ecological design)

Producers will have to create clothes according to eco design principles.

8. ubuntu [uːˈbʊntuː] - (noun) - A Nguni Bantu term meaning 'humanity'. It is often used in a more philosophical sense to mean 'the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity.' - Synonyms: (humanity, compassion, togetherness)

We know about ubuntu, we know about Ukama.

9. overarching [ˌoʊvərˈɑːrtʃɪŋ] - (adjective) - Comprehensive or all-embracing. - Synonyms: (all-encompassing, all-embracing, comprehensive)

But when they get into the boardroom, the overarching concern is price.

10. sentimental value [ˌsɛntəˈmɛntl ˈvæljuː] - (noun) - The importance of an object based on the emotions it evokes, not its monetary value. - Synonyms: (emotional value, personal value, intrinsic worth)

I suspect some of you are wearing something of cultural relevance, something of sentimental value.

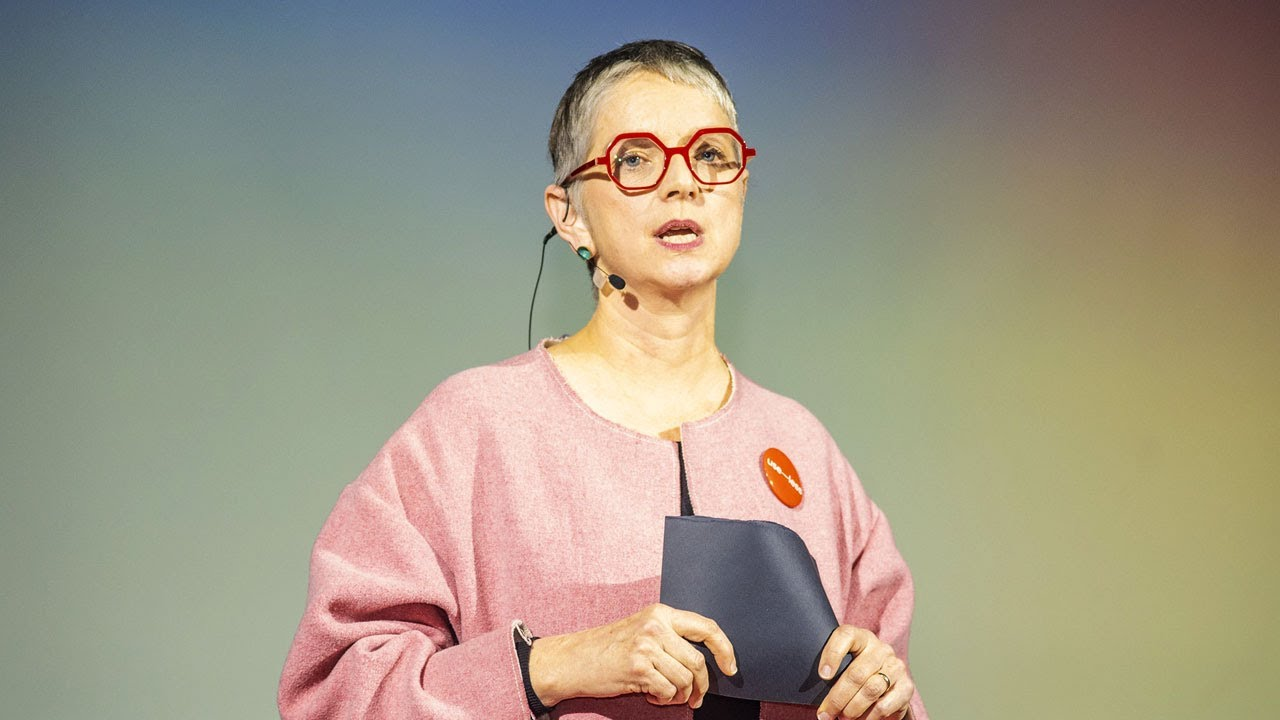

Dress to impress Mother Earth - Jackie May - TEDxJohannesburgSalon

I'm here to talk about sustainable development. Goal twelve responsible consumption and production. I believe if that we put care back into the way we produce, the things we consume, we can help us get to our targets. How we make and use things have become key drivers of pollution, carbon emissions and inequality. We've created these careless systems of consumption and production to meet not only our basic, basic needs, but our insatiable desires.

So, before I continue, I want you all just to think about what you're wearing. Do you know where it comes from? Do you know which woman was underpaid to stitch those fabrics together? Do you know what it is made of? Is it made of a natural fibre or of a fossil fuel based one? I suspect some of you are wearing something of cultural relevance, something of sentimental value, something that you cherish. Something you value. But I'd hazard a guess that most of you don't know who made it or what it is made from. And whether you can dispose of it responsibly, or whether it is safely compostable.

I'm the editor of Twig magazine. It's a fashion magazine. We're based in Cape Town, a place of extraordinary beauty. A place where we are reminded of the oceans and the mountain constantly. It's also a place where geography and urban design keep us apart. Black from white, poor from rich. It's a place where I cannot forget the crises of our era.

It's a time of these crises that I concern myself with. Fashion. Think me flippant, think me superficial, but hear me out. Over the last few years, seven years, I have spent hours, days, weeks, months, understanding the global fast, disposable fashion industry. It overproduces in a hyper consuming world, producing too much. In 2020, on average, we bought 60% more clothes than we did in 2014. We produce 100 billion garments a year. 192 million tonnes of textile is wasted every year.

In Cape Town alone, more than 6% of our landfills are filled with textile waste. We produce 10% of the carbon emissions. The world's total carbon emissions excess from the global north is sent to the global south, to countries like Ghana and Kenya, where you've seen it causes havoc in the natural environment. The Awe Foundation, a circular economy organization working in Ghana. I believe this is one of the most important organizations working in the circular economy in the world report that 15 million garments are imported into Accra or into Ghana every week. 40% of this is waste. Nothing can be done with it.

In the second hand market, it ends in rivers, in the lagoons and in the ocean. The same foundation reports that some parts of the beaches outside Accra are covered with textile waste, in some parts as deep as a metre and a half. This secondhand trade has also caused many people to be walking around our continent in branded clothing that has little cultural meaning to their lives or to their local economies. I've also got to understand our local industry, which in the 1990s was devastated by cheap imports and globalization, meaning thousands and thousands of people lost their jobs.

Globally, 80 million people work in this industry, most of whom are underpaid women. They're reports of child labor, forced labour. At the same time, some of the richest retailers and brands in the world are owned by the richest men in the world. So we're working in this careless system, and we know it, and we should care about it. We know about ubuntu, we know about Ukama. We know that to be fully human, we need to care not only about ourselves, but about each other and about our entire biophysical worlds. So how did we get here? How did we get into a state where we overproducing in a hyper consuming world?

As consumers and users of fashion, we overstimulated by the market. We have brands and retailers telling us constantly that we need to look stylish and we need to look current. They want us to buy new items of clothing every week. We see it all on social media. We don't cherish our clothes. They're easy to dispose of and they're super cheap to replace as industry.

We're operating in a global economy driven by market forces. We've created a linear system. We take things from nature, we make them and we throw them away. We don't take responsibility for the longevity of the clothes, nor for how long they last, or for the waste that they produce. I recently did an MPhil and I had the opportunity to speak to executives and retailers. I was asking them a specific question. I wanted to understand why they don't use more organic cotton. And the answer was the same.

Everybody was saying that in their individual capacity, people understand their responsibility. They know they need to do better. They know they need to do better for the environment, for land and for people. But when they get into the boardroom, the overarching concern is price. This merchant's model of doing business, buy low, sell high, is a real obstacle. It's impossible to buy better inputs because you've got to pay more for them in some cases, and it's impossible for businesses to become fully sustainable.

There's another example of an organization that knows, but doesn't do anything about it. It's a big sneaker brand. They've recently reported or published on their website that they know that their sneakers, which are mostly made out of plastic, are releasing microfibers into the environment. Plastic microfibers which are causing havoc in waterways, entering our bloodstream, killing marine life. What they're calling for is more stakeholder engagement, more research, consumer solutions. But the one thing they're not calling for is a halt in production. While they find these solutions, they've put a value on their shoes, but not on nature.

So what do we do about this? At Twig? We try to understand the problem and how we got here. And secondly, what we do is we try and find examples of people who care and who are trying to transform a system into one that cares and connects us to nature and to each other.

So we interview people. The late climate change scientist, the south african scientist Bob Scoley, said, we're not going to change behavior on the basis of hard fact. We can only change behaviour through a deep emotional connection. So through our storytelling, we hope to connect people to those who care about land and people, and we hope to get them to migrate their spending to those who care.

Recently, I spoke to the founders of. It wasn't me, actually, it was one of my team members spoke to the founders of Soul Shoes, a sandal company that makes sandals out of waste tires. And they said, we shouldn't have to force people, we shouldn't have to force consumers and producers to do better. We should all want to make the world a better place.

I've got more examples. There's an organization in Lipopo called Karos. They give over 1000 women embroidery, thread and cloth to make the most beautiful products in their homes. Across the rural areas, there's a young designer called Katleju Mukwana who is making the most beautiful sustainable fashion. And she uses natural botanicals and tea to colour her 100% cotton clothing to give them also to make them beautiful. She's an example of a sustainable fashion brand that is fashion forward and really fun.

I've seen the cracks in the system, I've seen the new worlds emerge. So on a systems level, policy is driving change. And here, Europe is pioneering this change. Soon, producers will have to create clothes according to eco design principles, using better imports. Making clothes last longer. Users of clothing will be rewarded for repairing their clothing. And producers will also have to be responsible for waste throughout the lifecycle of the clothes, from the beginning, throughout, and then even after we finished wearing them.

In South Africa, the retail clothing, textile, footwear and leather master plan for 2030 is encouraging localization to bring jobs back to the country. I went to visit a TFG factory recently and they are really increasing their local production, creating more jobs, and at the same time they're increasing manufacturing practices. We all have a role to play as consumers and users of fashion, we need to make better choices. As producers, we need to offer people better options. And as regulators, we need to create an environment for this all to happen.

So I envision a system, a fashion system that produces far less. It operates in a circular and a wellbeing economy. Clothes are made to last. We wear them longer. We learn to repair them, we swap them. The people who make our clothes are well treated. Nothing, no toxins and no plastics are used in our fashion.

So before I conclude, I'd like to just ask you to think about your clothes again. And think about the questions I asked you. I asked you who made them. I asked you what they were made of. I'd like you to think of a few more things. Not all of this is attainable immediately. But when you next need something, will you buy something new? Will you buy something secondhand? Will you rent it? Will you swap it?

And if it is something new, will you think about what fabrics it's made out of? Is it a natural fibre? Will you take good care of it? Will you wear it often? I want us all not to be just producers and not just consumers. I want us to be repairers and carers. Thank you.

Sustainable Fashion, Environmental Impact, Social Responsibility, Global, Entrepreneurship, Economics, Tedx Talks