The speaker shares a deep-rooted passion for science, heavily influenced by his father, a scientist at Johns Hopkins University. From childhood, his father nurtured his curiosity with detailed scientific explanations. The speaker embraced science from a young age, displaying prowess in electronics and later getting actively involved with various science projects. His journey took him to prestigious institutions like Caltech and Columbia, where he moved from contemplating electrical engineering to finding a fascination in physics, particularly quantum mechanics.

His pursuit of quantum mechanics, though met with skepticism from the academia, was greatly inspired by John Bell's paper. Despite being told by notable physicists that his ideas contradicted established theories, the speaker persevered, conducting experiments that challenged the core tenets of quantum mechanics. Supported by a few, including Nobel laureate Charlie Towns, he forged ahead with passion, contributing to major debates and advancements in physics through the CHSH inequality.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. aeronautics [ˌɛrəˈnɔːtɪks] - (n.) - The science or practice of building or flying aircraft. - Synonyms: (aviation, flight engineering, air transportation)

...creator of the aeronautics department at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

2. bathed [beɪðd] - (verb) - To be completely immersed in or surrounded by something. - Synonyms: (immerse, soak, engulf)

But I just was sort of bathed in it.

3. enamored [ɪˈnæmərd] - (adjective) - Filled with a feeling of love or admiration for something. - Synonyms: (charmed, captivated, fascinated)

...and so very quickly got enamored with doing physics.

4. thesis [ˈθiːsɪs] - (n.) - A statement or theory that is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. - Synonyms: (dissertation, proposition, argument)

And there I was working on my thesis project...

5. cosmic microwave background [ˈkɒzmɪk ˈmaɪkrəweɪv ˈbækˌgraʊnd] - (noun phrase) - The thermal radiation left over from the time of recombination in Big Bang cosmology. - Synonyms: (CMB, relic radiation)

...my thesis project was on the cosmic microwave background.

6. theorem [ˈθiːərəm] - (n.) - A general proposition not self-evident but proved by a chain of reasoning. - Synonyms: (proposition, hypothesis, postulate)

What Bell's theorem, and in particular the...

7. inequality [ˌɪnɪˈkwɒlɪti] - (n.) - The condition of being unequal; the lack of equality. - Synonyms: (disparity, imbalance, difference)

Since I kind of was the inventor of the CHSH inequality...

8. skeptical [ˈskɛptɪkəl] - (adjective) - Not easily convinced; having doubts or reservations. - Synonyms: (doubtful, distrustful, suspicious)

So one of the things that my dad did that helped me along was taught me to be skeptical of everything...

9. pseudoscientific [ˌsuːdoʊˌsaɪənˈtɪfɪk] - (adjective) - A collection of beliefs or practices mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method. - Synonyms: (fallacious, spurious, unscientific)

I am the world's worst critic of pseudoscientific claims.

10. ammeter [ˈæmˌmiːtər] - (n.) - An instrument for measuring electric current in amperes. - Synonyms: (current meter, electrical tester, multimeter)

I had an ammeter on the solar panels and watch.

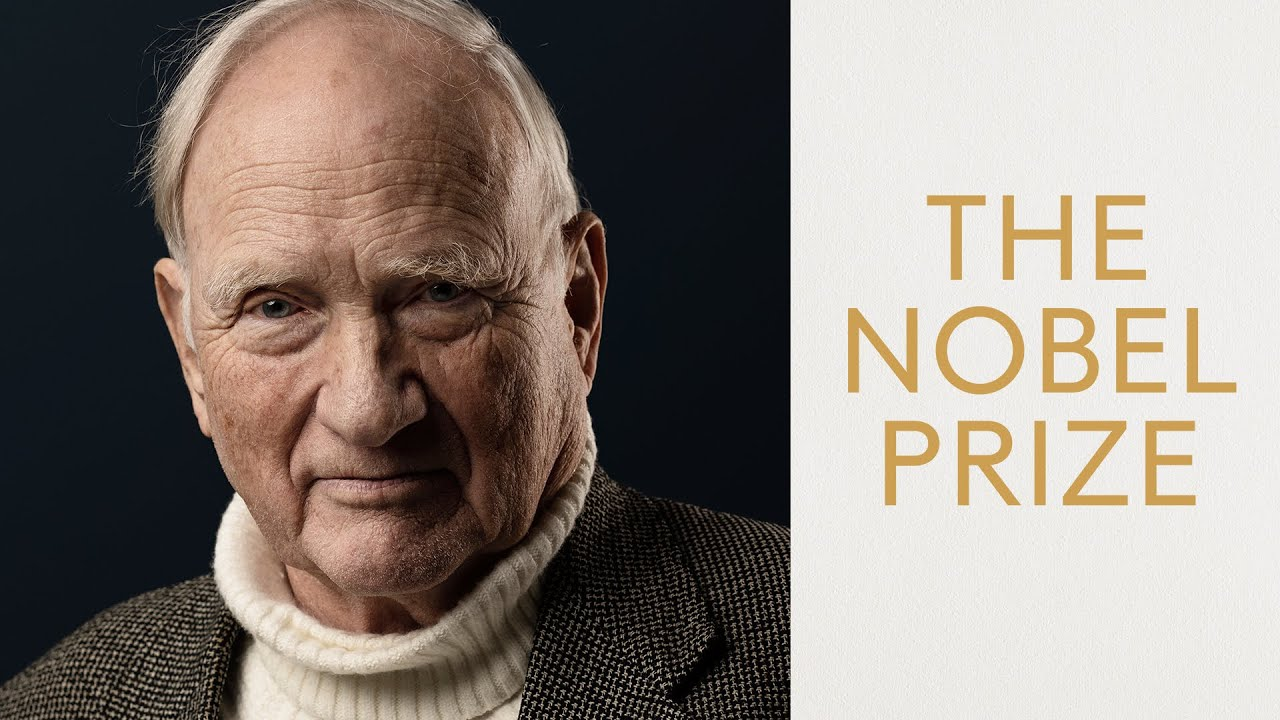

John Clauser, Nobel Prize in Physics 2022, Official interview

Where does your passion for science come from? Oh, I think that's very clear. My dad was a scientist, and when I was a kid, he was professor, in fact, chairman or indeed the creator of the aeronautics department at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. And I would routinely and all of my primary life leading up to this, every question I asked, he would answer in gory detail, very patiently with me, and I just soaked it all up. And then when I was in high school, I would take the bus up from Baltimore Polytechnic in Baltimore and walk across the campus to his office, where I was supposed to be doing my homework, waiting. And then he would drive us home, and instead I would just wander all over the campus into all various laboratories, into his laboratories, and I would walk in and look at all these marvelous pieces of devices sitting around and say, boy, when I grow up, I want to be a scientist. Look at the great toys they get to play with. But I just was sort of bathed in it. Since I was a very young kid. I loved science. My dad taught me lots of it. I was a high school whiz kid in electronics, built a whole bunch of computer science projects, even won a few national affairs. I was just having fun. And my parents left me as a free range kid. I could do pretty much anything I wanted and did, wandered all over the city. And one of the things that I enjoyed, I was a member of a high school radio club, just built a lot of electronics, and I was having a blast doing it all.

When did you know you wanted to pursue quantum mechanics? When I went to Caltech, originally, I was thinking about electrical engineering, but very quickly realized, no, no, I think I want to do physics. Caltech was a marvelous place. Some of the greatest physicists in the world watered the halls there, and so very quickly got enamored with doing physics. So in all of which, I was just having fun. I enjoyed doing a lot of it. I was not as good a student as I probably could have been. I was the, I was the social chairman of our residence house, Dabney House at Caltech, threw some great parties and flunked out a bunch of freshmen who really weren't going anywhere anyway. So probably best thing for them, and somehow, I have no idea how, got into graduate school at Columbia. And there I was working on my thesis project was on the cosmic microwave background. We were going to put a really, we were going to put a radio telescope and a high flying u two apparatus, sort of where I learned a little bit about the spectrum of water vapor in the atmosphere relative to climate change. But then, so we ended up not doing that. Ended up looking at interstellar cyanide and making the third measurement of the microwave background.

Would you consider yourself to be a good student in order to get your degree at Columbia? There were, I think, five important courses. You had to get a b or a better, otherwise you were considered having flunked. And so quantum mechanics. I flunked twice. And so I think finally my Nobel lecture will explain why I flunked, what was driving me nuts, and why I still don't understand quantum mechanics. What was the reaction people had to your theories? Much to the stress of my thesis advisor, in fact, most of the stress of the whole Columbia physics faculty. Everybody told me this was. I was totally nuts in doing this. Everybody knew that Einstein was wrong, that the. He was getting senile frequently was the claim. And the Bohr had it all right. I couldn't understand Bohr at all. So then I ran across John Bell's paper, and that started my whole career in studying quantum mechanics. That was while I was still a graduate student. Columbia had more physics Nobel laureates than I think Caltech did. And they all told me, you're not doing this. And when I was doing the experiment at Cal Berkeley, my dad, who was then on the physics faculty, he was on the edge. He was dean of applied science and engineering at Caltech. And he would go home to Pasadena for Christmas and his birthday and thanksgiving and whatever. And so I was down there for Christmas, didn't he? Oh, I have made an appointment for you to talk to Richard Feynman. Oh, okay. I was doing the experiment, so I tried to get. So I walked into the Feynman's office, and he threw me back out instantly. He was actually angry, as best I could tell, that I was doing an experiment to test the predictions of quantum mechanics. Everybody knows predictions of quantum mechanics are perfect. Don't even need to look. And I think his line was, if you find something wrong with quantum mechanics, the predictions of quantum mechanics, you can come back then and we'll talk and figure out what your problem was or what your problem is. Dismissed me immediately. So anyway, he was rather abrupt.

Did you find people who supported your work? And then when I was at Cal Berkeley doing the, trying to do the experiments, the only, there really only two people, or maybe three later on that thought it was actually a good idea. Charlie Towns is a Nobel laureate, of course, and Howard Shugaard was a great atomic physicist there. Fortunately allowed me to stay there for 69 to 76, where I did, like, four different experiments. So I had a great time. I was having fun. Even though I had destroyed my hero Einstein's work, I was not very happy about that. But that's what the data kept telling me. I got to report what I see. That's what experimental science is all about. Literally, you're talking to God, and God has spoken. It was not easy getting into a position to do the experiment. Absolutely not. I struggled to do that. And like I say, it was only through the kindness and generosity of towns and shugaard that I stayed on.

What was the hardest part of getting people to pay attention to your work? The hard part was. I mean, was getting around. This was a religion among physicists. And in fact, even in the Bohr Einstein debates with Frodinger, also the universal religion was quantum mechanics. Makes correct predictions, period, off the table. And so what? Bell's theorem, and in particular the. Our version of it, the Klauser Horn Shimoni Holtz experimental prediction, showed that either that had to be wrong or Einstein's whole legacy had to be wrong. I think at the time, people who were critical of doing the experiment didn't realize, really what was at stake, that it was that cut and dried between two religious icons, if you will, the field of physics. Since I kind of was the inventor of the CHSH inequality and the ch inequality and all that, I knew exactly what it was all about. But it took a long time for that to filter in.

What advice would you give to a student or young researcher? Yes, I would, definitely. I mean, if you're not enjoying it, find something else that you are enjoying, and then you can put your heart into it and really be good at it. Totally silly to waste your time if you're not enjoying what you're doing.

How do you see science? Why do you think science is so special? Okay, to start out with, I'm an atheist from that point of view. But literally, when you go into. At least I feel this way. When you go into a physics laboratory, you're talking to God, and it's like going into a church asking a question of God. And it's not often that people will walk into a church and say, all right, God, what's the mass of an electron? Nonetheless, if you ask a question carefully, you will get a definite answer. And it's an unusual church from that point of view. If somebody else asks the same question and walks into another church, he or she will get exactly the same answer. Find me another church for which that is true, that you can. That two people can walk into different churches, ask the same question, and get the same answer. Enough said. Nature is beautiful. There is great magistrate in all of the natural patterns you probably heard the comment about. To look on Maxwell's equations is to look on the work of God. There is great beauty in the symmetries that are built in. And if you're the first guy to see something new, some new patterns in nature that nobody has noticed before, it's an awesome experience, realizing that you're the only person in the whole world who knows this, and you have communed with nature as no one else has in the past. It's a truly marvelous feeling. It gives you a great spiritual feeling.

What qualities do you need to be a successful scientist? So one of the things that my dad did that helped me along was taught me to be skeptical of everything, especially other people's interpretations of experiments. And if you and you would say, okay, go back and look at the original data, if you possibly can, what was really done, and be skeptical that they have drawn the right conclusions. And I do that to this day on everything. I am the world's worst critic of pseudoscientific claims.

What has sailing taught you as a scientist? I raced across the Pacific Ocean any number of times. You learn a lot about clouds, and it was using solar power for the instrument systems, and every time, and I was just sitting there in my berth watching, and I had an ammeter on the solar panels and watch. Every time we go under a cloud, the total current charging their batteries would drop to one half. Why? Why is that almost exactly one half? And in and out of clouds. Flick, flick, flick, flick goes the needle. Amazing. It gave me a whole different opinion of how climate change works. And I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what makes sailboats go fast, how to win races, built a lot of hardware. The present boat, the rudder that came on the boat was a total joke. Slow, you couldn't steer the boat. It had a lot of drag. And so I just tore it out and built a whole new one in my backyard. Rolls of carbon fiber cloth and buckets of high tech epoxy and boards of polyurethane foam, and put the whole thing together. It was fun. I mean, I didn't know how to do it to start with, but I taught myself along the way. It's not that. And doing the stress analysis is pretty straightforward. If you're a physicist, it's a piece of cake. This is straightforward handbook engineering. So.

Science, Technology, Education, Quantum Mechanics, Inspiration, Physics, Nobel Prize