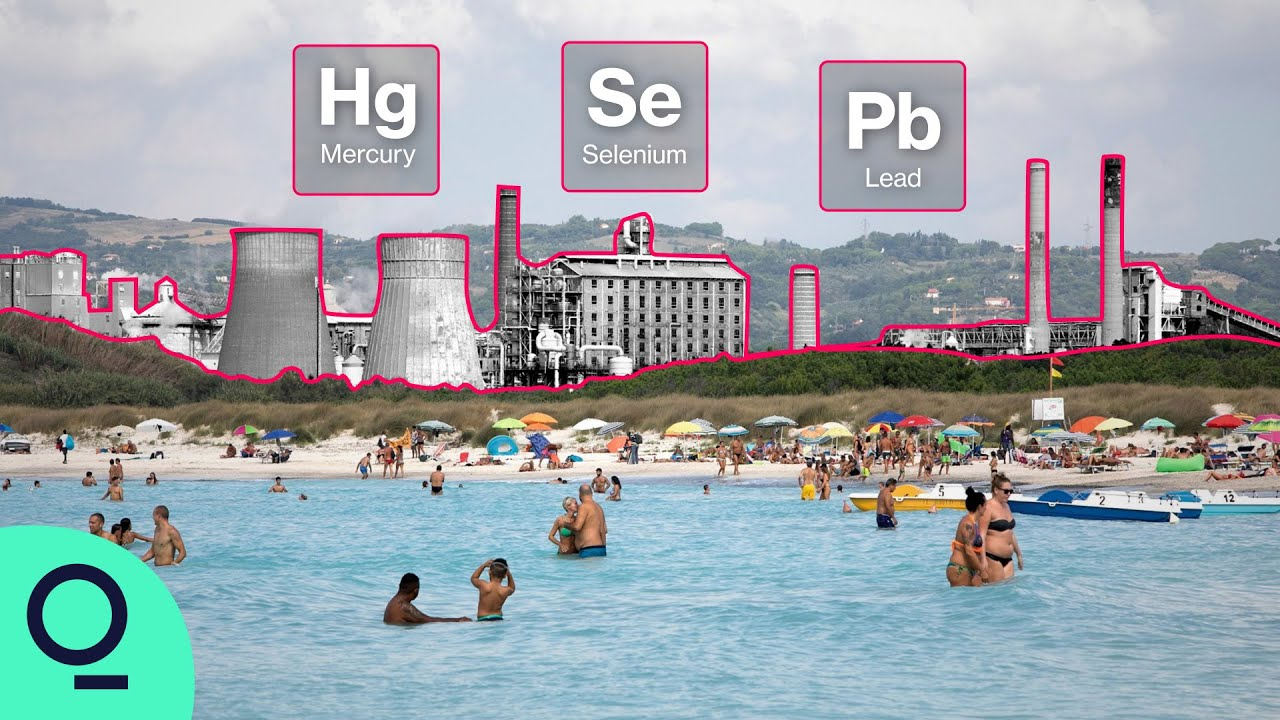

The video explores the environmental and legal issues surrounding a chemical plant operated by the Solvay company in Tuscany, Italy. Although the beaches in the area attract tourists due to their strikingly white appearance, this beauty conceals the significant environmental impact caused by industrial discharge over the years. The plant uses local limestone to produce soda ash, and the waste product, which includes heavy metals, is discharged directly into the Mediterranean Sea, raising concerns about its environmental footprint and potential health effects on the local community.

Questions have arisen regarding the legality of Solvay’s practices, given that Italian law allows certain levels of heavy metal discharge. However, evidence suggests that Solvay exceeded these limits in the past, leading to a legal settlement instead of a trial. Activist groups and local communities remain concerned about the lack of transparency and accountability, while the company claims compliance with legal standards through changes in accounting practices rather than actual reduction in emissions.

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. discharge [ˈdɪsˌtʃɑrdʒ] - (n. / v.) - The release or emission of substances such as chemicals or pollutants. In this context, it refers to the chemical waste released into the sea. - Synonyms: (release, emission, outflow)

It's discharged straight onto the coast and into the coastal water.

2. multinational [ˌmʌltiˈnæʃənəl] - (adj. / n.) - A company that operates in multiple countries around the world. Solvay is described as such due to its worldwide operations. - Synonyms: (international, transnational, global)

Solvay is a multinational chemicals company based in Brussels, Belgium.

3. erosion [ɪˈroʊʒən] - (n.) - The process by which earth and rock are worn away by natural forces such as wind or water. - Synonyms: (wearing away, degradation, abrasion)

...helping the beach not fall victim to erosion...

4. concentration [ˌkɒnsənˈtreɪʃən] - (n.) - The amount of a substance contained in a solution or mixture. In the document, it refers to the levels of heavy metals in Solvay's discharge. - Synonyms: (density, strength, purity)

...reflects the concentration of heavy metals in the discharge.

5. plea bargain [pli ˈbɑːrɡən] - (n.) - An agreement in a criminal case where the defendant pleads guilty to a lesser charge to avoid trial for a more serious charge. - Synonyms: (deal, arrangement, agreement)

It went to a plea bargain for polluting the beach around the plant.

6. effluent [ˈɛfluənt] - (n.) - Liquid waste or sewage discharged into a river or the sea. - Synonyms: (waste, discharge, run-off)

...the effluent in a way that the fact that they were exceeding legal limits...

7. viable [ˈvaɪəbl] - (adj.) - Capable of working successfully; feasible. In the context of Solvay, it refers to the plant's continued operation. - Synonyms: (feasible, workable, practicable)

...and being viable and not having found to have violated any laws or have problems with disclosure...

8. disclosure [dɪsˈkloʊʒər] - (n.) - The action of making new or secret information known. - Synonyms: (revelation, exposure, announcement)

...or have problems with disclosure, they need everything to go right for them.

9. uprising [ˈʌpraɪzɪŋ] - (n.) - An act of resistance or rebellion; a revolt. - Synonyms: (revolt, rebellion, insurrection)

They're facing it with an uprising from this activist investor.

10. relabel [riːˈleɪbl] - (v.) - To assign a new label or classification to something. - Synonyms: (rename, reclassify, rebrand)

It has simply relabeled some of the plants processes.

This White Italian Beach Has a Dark Secret

If you were here in August and you were sitting on the beach on a blanket facing the sea, you would think you were in the Turks and Caicos. In the Caribbean, the beaches have been renamed spiagg bianche in Italian, which literally means the white beaches. And you'll see, you know, hundreds of beachgoers flocking to that destination in the summers. Vogue Italia magazine put the white beaches on its cover. I mean, it's strikingly beautiful. But this sort of Caribbean like oasis also has a dirty secret.

Well, here's this enormous chemical plant on the beaches of Tuscany, and for over 100 years, it has been pumping 24, 7365 days a year. It's discharged straight onto the coast and into the coastal water. It's visible on the beach. It's visible from space, even so much so that it has literally transformed, warmed the landscape. The beaches are now a stark and bright white, whereas all around that area, the beaches are sort of a more beigey color. And the question that came up is, how could that possibly be legal, that a chemical plant can just take leftover and just pump it out into the sea?

And so we set out to answer that question, you know, is it okay? Is it damaging the environment and hurting people? And the answer was actually more complicated than we thought it would be. Solvay is a multinational chemicals company based in Brussels, Belgium. It's got a market value of far over €10 billion. It's operations all around the world.

Well, here's a town, Rossignano solve, which, as the name suggests, takes its name from the company for a reason. Over 100 years ago, when Solvay spotted this location on the coast of Italy, as infrastructure was being built around it, it found a location which would be suitable for its production and literally built a town around the plant. We were talking schools, we were talking a hospital, a theater. And so this town is literally the embodiment of the company and its plant in Tuscany. This is a plant that makes soda ash, an ingredient in glass, and it's used for other things. And essentially, they take local limestone from quarries and bring it in and pulverize it.

Well, essentially, what is being discharged are tiny, tiny particles of limestone mixed in seawater, and that is what is making the beach, in part, that color. Their position is they take locally quarried natural stone, and they put it through their plant, and that the totally natural sandy byproduct is just pushed out to the sea, where it does a terrific job contributing to the environment by helping the beach not fall victim to erosion, but the process itself of pulverizing the stone unlocks natural metals, minerals that are inside the stone. Arsenic, mercury, zinc, lead. Some of it is dissolved in the water, and some of it is still in particles, in compounds that are part of the rock.

And every year, they pump the equivalent of almost 250,000 tons of these suspended solids directly onto the beach and into the Mediterranean. The italian government would, as they just have reauthorized them with a new license, they get their stamp of approval, and it seems there that life goes on. Except that we've been able to answer part of the question about, is it legal? Should it be legal? Well, under italian law, the one legal standard the company has to meet reflects the concentration of heavy metals in the discharge. What that means is it cannot exceed certain thresholds of milligrams per litre of heavy metals in its discharge. And it turns out that in 2013, it had exceeded those concentration limits, and it never went to trial. It went to a plea bargain for polluting the beach around the plant, and of diluting the effluent in a way that the fact that they were exceeding legal limits, such as mercury, that were going directly into the Mediterranean.

And this is a turning point. Solvay promised to the court that it would somehow treat for those heavy metals to reduce the concentrations. The result was that solvate has not changed how it produces soda ash, nor how it discharges the pollutants. It has simply relabeled some of the plants processes. They're taking seawater, which doesn't count to their fraction normally, because it's just used to cool all the hot stuff in the plants, not part of the production itself. It's cooling.

Water comes in from the sea, goes out, doesn't count towards their concentration. They built something in treating for ammonia that routed about a third of this seawater through a new apparatus that they built that let them raise the denominator of their fraction. So without changing the amount of heavy metals coming out of the bottom, half of that got higher and higher as they put online this new system. And now it's almost impossible to tell if they have any heavy metals going out the door.

The company is very straightforward. We asked them, have you reduced the amount of heavy metals? And they said, no, nothing that we've done. Reduces the concentrations, increases the concentrations unchanged. But what they have done is accounted for water differently. Well, in an email exchange with us, the company asserted that the italian court never determined that the crimes were committed.

A really key turning point was getting the paperwork from the court, which we were able to make a special request by citing public interest in our status as journalists to get the actual documentation of what happened in court that day. And it says by how much mercury limit was exceeded by six times over 50%, over 30% over that. Having these raw numbers and then going back and seeing it's never been in any of their filings to shareholders. They've never described it that way. They don't really ever talk about it, and seemed like it was kind of an important moment. And so we knew that we were seeing a difference between what was being presented to the public, being presented to investors, and the hard documentation. And that hard documentation had never come out before.

The idea that this is going on 365 days a year with no attempt to hide it. There's no wall behind which you need to pier. There's no boundaries around this trench that literally goes into the sea. And, you know, in the summers, I've seen it with my own eyes. There are people literally bathing right on the ditch, right where the discharge enters the sea. The water is a little bit warmer. Perhaps that's what attracts some of the bathers.

And the community that lives around this plant has elevated levels of diseases. Showing causality always difficult, but there is a lot that the activists have gotten their teeth into about showing that there is an impact. La mortalita pertu teleca no nhs. La mortalita de la parato genizo urinario santa circa la mortalita pertumore alama melaness alternate grossomado tuti son conspiracy. Ma unajosa farqualcosa per reagira, percudere loscari tantospatio. Activists have described the attitude here as resignation. Some people don't want to know what's in the air and in the soil. We spoke to some of the residents, most of whom were rather indifferent to the plant. Even the lady who lives right on the footsteps of the plant sort of shrugged her shoulders and said, you know, you've got to die of something.

And when we made our way to the plant's entrance, well, the reception there was quite frosty. We came here, and security at the front gate of the plant stopped Elisa because she was taking pictures, and they threatened to call the police. And so she joked this morning that, you know, be careful when the police stop. You see, they don't break your cameras. Sure enough, when we were filming our interview with an activist on the beach, men in plain clothes came up behind us, and we were done. Flashed their badges and wanted to see id and wanted to know who we were working for. You don't get close to this plant without somebody knowing who you are, what you're doing, and making you feel a little uncomfortable about being here.

I think the trouble with the regulation, as we found, is, in part, the disjointed nature. On the one hand, you have the courts. They enforce the law, they prosecute. On the other hand, you have the environment ministry, which is now in charge of regulating and allowing solvate to operate a plant. It wasn't clear to us just how much communication there was between, for example, the courts and the environment ministry. We know that prosecutors are looking at Solvate again, though, it's not clear what the basis of their investigation might be, how advanced and who it might be focusing on.

So you've launched a pretty high profile campaign to get the CEO of Solvay removed. Another important turning point was the entry onto the scene of Bluebell, an activist investor group based in London. And, you know, every year they pick another target and buy one share. In this case, they bought one share of Solvay and they went after the company for its italian plant.

And what this did was create a ton of publicity around this and raise some really good questions. And what caught our eye was at the 2021 shareholders meeting, they asked a lot of questions about the water flowing in, the water flowing out, and they didn't get a lot of answers. They got a lot of apples and oranges. Figures from the company. Companies certainly didn't tell them what they could have, which was that they had changed how they account for the water. Starting in 2019, what happens next is Solvay is facing a litany of challenges.

They're facing it with a potential prosecution in the Livorno courts. They're facing it with an uprising from this activist investor. They're facing it from activists who are energized by the fact that someone had no idea that the government here in Italy was about to renew their license for another twelve years. And that renewal there is really important to them. And staying in business here and being viable and not having found to have violated any laws or have problems with disclosure, they need everything to go right for them. Not just because this is, you know, 17% of their global business and one that they want to sell or dispose of, but because it could affect their stock.

I mean, all ways you can see it, the fact that they're pushing back against this activist investor and trying to discredit him with public statements, this is a turning point for this company. As things stands, there are no indications that Solvay intends to change this process in this particular location. And the change will probably have to come from above. The change will probably have to come from policy that is updated to reflect the norms and practices that are used elsewhere. But it is astounding that no matter what is being discharged, the sheer volume of it and the fact that it's affecting the landscape is carrying on and has been carrying on for decades.

Environmental Impact, Chemical Industry, Activism, Economics, Global, Technology, Bloomberg Originals