The video focuses on the dire situation surrounding the Nairobi National Museum, which holds an invaluable collection of fossils and diverse specimens crucial to human history and biodiversity. The museum houses approximately 10 million specimens, including renowned fossils such as the turkana boy. However, due to severe funding shortages and poor facilities, the collection is at risk of deterioration and loss. Despite its global significance, the museum struggles to maintain its collection in proper conditions, fighting against issues like outdated storage, insufficient space, and antiquated record-keeping systems.

The museum's challenges are compounded by internal issues such as a recent corruption scandal which harmed its ability to secure necessary funding. An international coalition, including notable paleontologists like Louise Leakey, is making efforts to revitalize the museum. They aim to obtain the necessary funds to upgrade the facility, expand storage centers, and digitize records. The support from the Smithsonian and other global partners highlights the museum's importance not only in Africa but also for understanding human evolution on a global scale.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. repository [rɪˈpɒzɪtəri] - (noun) - A place, building, or receptacle where things are or may be stored. - Synonyms: (storage place, depository, storehouse)

Years of limited resources and a severe lack of funding have left this priceless repository of the past in a state of dilapidation and decay.

2. hominin [ˈhɒmɪnɪn] - (noun) - Refers to the group consisting of modern humans, extinct human species, and all our immediate ancestors. - Synonyms: (ancestral human, human ancestor, proto-human)

Tom Mikuyu is the collections manager of the Nairobi National Museum's hominin vault.

3. paleontologist [ˌpeɪliɒnˈtɒlədʒɪst] - (noun) - A scientist who studies fossils to learn about the evolution of life on Earth. - Synonyms: (fossil scientist, geoscientist, archaeologist)

paleontologist Louise Leakey is the director of Public Education and Outreach at the Turkana Basin Institute.

4. dilapidation [dɪˌlæpɪˈdeɪʃən] - (noun) - The state of falling into decay or being in disrepair due to neglect or time. - Synonyms: (decay, deterioration, ruin)

Years of limited resources and a severe lack of funding have left this priceless repository of the past in a state of dilapidation and decay.

5. corruption scandal [kəˈrʌpʃən ˈskændəl] - (noun phrase) - A situation in which a person in power acts dishonestly, typically involving bribery or fraud. - Synonyms: (fraud case, bribery scandal, unethical practice)

Making matters worse, the museum was recently engulfed in a corruption scandal, further undermining the museum's efforts to procure funding.

6. turkana boy [təˈkɑːnə bɔɪ] - (proper noun) - The name given to a nearly complete fossil of a Homo erectus youth, one of the most important discoveries for the study of human evolution. - Synonyms: (Homo erectus youth, Nariokotome Boy, fossil find)

Stored here is the museum's most famous fossil, the turkana boy, which is one of the most complete Homo erectus skeletons known to science.

7. accession cards [əkˈseʃən kɑːrdz] - (noun phrase) - Records that provide information on items entering a collection, such as a museum or library. - Synonyms: (catalog cards, entry records, inventory cards)

I mean, the staff in the department here working really hard to create the labels, the accession cards, and do as best they can with the resources that they've got to keep this collection safe.

8. entomologist [ˌɛntəˈmɒlədʒɪst] - (noun) - A scientist who studies insects. - Synonyms: (insect scientist, insect specialist, bug expert)

entomologist Dino Martens is exploring the backroom of the museum's vast insect collection.

9. herbarium [ərˈbɛəriəm] - (noun) - A collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study. - Synonyms: (plant collection, botanical museum, flora archive)

In February, Duke University announced it would be closing its herbarium, which is home to a collection of over 800,000 plant specimens.

10. digitizing [ˈdɪdʒɪtaɪzɪŋ] - (verb) - The process of converting information into a digital format. - Synonyms: (computerizing, digitalizing, converting to digital)

During that visit, the Biden administration announced it would fund an initiative to send Smithsonian experts to Nairobi to assess the museum's needs and plan a roadmap to reform, which would likely include digitizing records and modernizing storage facilities.

Why a Museum Housing Some of Humanity's Oldest Bones Is in Peril - WSJ

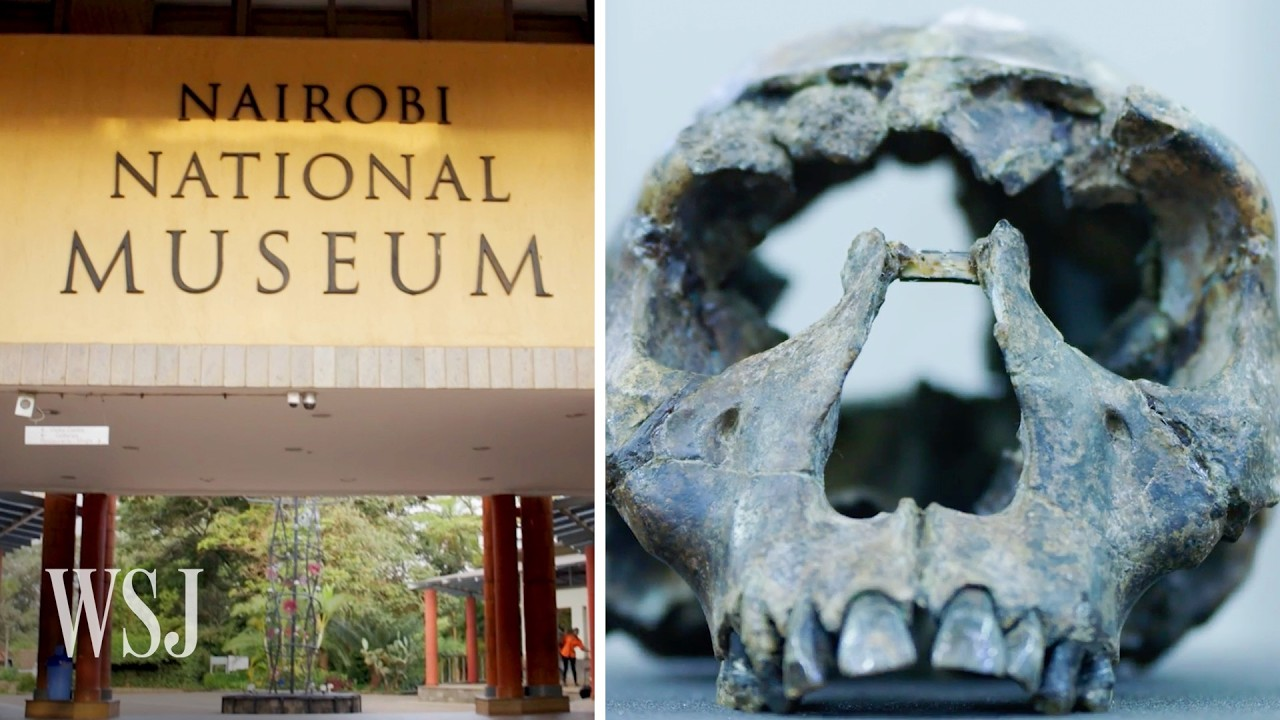

Tucked within the dusty backrooms of the Nairobi National Museum are million year old fossils. An unparalleled collection of insects, tens of thousands of bones and a fossilized skeleton. Crucial to our understanding of humanity, it is one of the most important biodiversity resources in Africa. And because of that, it's also of global importance.

Despite its significance, the Nairobi national museum's roughly 10 million specimens are at risk. Years of limited resources and a severe lack of funding have left this priceless repository of the past in a state of dilapidation and decay. You've got labels that are sort of lying loose, you've got bits and pieces that are in bags. Things are getting lost, records are getting lost. So it is in real urgent need of attention. Seeing these variable corrections on the floor. This is one of the areas that causes a lot of anxiety.

Making matters worse, the museum was recently engulfed in a corruption scandal, further undermining the museum's efforts to procure funding. Now an international coalition of scientists is racing to save the museum and secure the millions needed to overhaul it. Their goal is to restore the institution and its collection to a state more befitting its immense importance to humanity.

Tom Mikuyu is the collections manager of the Nairobi National Museum's hominin vault. Stored here is the museum's most famous fossil, the turkana boy, which is one of the most complete Homo erectus skeletons known to science. Most museum visitors only see a replica of this fossil in the museum's exhibition space. But we were granted a rare opportunity, a peek at the original fossil.

This is all the skeleton of turkana boy. This is the cranium, the spine, the legs, right ribs, the left ribs, the hands and upper limbs. Pelvis fossils housed in the vault enjoy luxuries unavailable to the rest of the museum's collection. The vault is bomb proof, air conditioned and carpeted. It's Kenya's most prized fossil. It's like the crown jewel of the paleontological collections.

paleontologist Louise Leakey is the director of Public Education and Outreach at the Turkana Basin Institute. The significance of the turkana boy is largely that it's so complete. Despite being approximately 1.5 million years old, the turkana boy fossil is only missing a humerus, hands and feet. The turkana boy's remains were discovered in northern Kenya in 1984 by by a team led by the scientist Richard Leakey, Luis's father.

The storage standards of the hominin vault contrast sharply with the rest of the museum's backrooms, which tend to be decades out of date and severely under resourced.

You know, look at this. This is very precarious, right? Sitting on a bit of foam and it wobbles. So that could very easily get knocked off. And it's an early, very early elephant.

This thing should be much safer. And the broken bits that have come off it, they need to be stuck back on again because otherwise it's going to get lost. One of the museum's biggest challenges is a lack of space. Some of the largest and most impressive fossils are housed in dusty corners, on crumbling mattresses, or in locations that seem to invite an accident.

These are a couple of elephant tusks in here. This one's obviously, the tip's been broken, it's fallen off. But, you know, these are not very easy to move, so if you want to get these out, you can't get them out in these stacks, they're on foam that's perishing. They're breaking because the glue is aged. We need a different way to store these collections as soon as possible.

On the paleontology floor, uncounted thousands of fossils, some as old as 3 million years, are kept in decrepit, often ramshackle conditions not befitting the collection's importance to science. In any one tray, there's, you know, 100 odd specimens, and you can't see those specimens, and unless you leaf through them to find the number and the card, so it's quite hard to find anything in this collection as well.

Another problem is the collection's antiquated record system, which is still based on handwritten note cards. These cards are unique. There are no more of them. If you pull out a card, it will tell you where it is stored in the lab. So if we were to have a fire and we were to lose these cards, we would lose all context. We wouldn't know where anything was or where it came from. So in some ways, this information is as important as the collection, the fossils themselves, because a fossil without context has no relevance, it has no meaning.

My hands are absolutely filthy because of the dust. These bags are falling apart, just literally perished, right? And all of these pieces are then going to get mixed up with everything else in this bag, and you're going to lose the labels, and the writing on the outside is disappearing as well. So it's not. Not great.

The Leakeys are perhaps the world's most renowned family of paleontologists. Fossil excavations done by Louis, grandfather Louis, grandmother Mary, father Richard and Mother Meave upended humanity's understanding of early humans. Until the 1950s, scientists believed that Homo sapiens evolved in Europe or Asia about 60,000 years ago. But thanks to the Leakeys, we now know that Homo sapiens actually emerged from Africa much earlier, about 200,000 years ago.

It's very frustrating to see the collections in this state because they just haven't had any investment. The Kenyan government only funds staff salaries at the museum. This is partially because Kenya is facing a financial crisis of its own. This summer, violent protests gripped the country after the government proposed unpopular tax increases. The museum's operating revenue comes mainly from ticket sales.

The museum said it expects to take in about 300 million Kenyan shillings, or $2.3 million annually from ticket sales. That the museum functions at all is largely thanks to its dedicated staff. I mean, the staff in the department here working really hard to create the labels, the accession cards, and do as best they can with the resources that they've got to keep this collection safe. It's because they care that this thing continues, because there's some very good Kenyans, lots of potential, lots of amazing young scientists that are upcoming.

This could be an extraordinary collection if it had the financial backing to upgrade it. Many of the fossils housed in the museum were found 400 miles north of Nairobi in Kenya's Lake Turkana region. Lake Turkana is the world's best field laboratory for the story of human ancestors. There's nowhere else like it in the world.

Today, luis and her 13 person team are doing what the Leakeys have done for decades, fossil hunting. There's nowhere else quite like this, both in terms of its scale, its size and the depth of time that's preserved here that is so easy to date, using sort of the geological ash horizons which give you very accurate dates.

Extending from northern Kenya into southern Ethiopia, Lake Turkana is the largest permanent desert lake in the world. Stretching almost 155 miles from north to south. Surrounded by arid, harsh terrain, the lake is known for its high winds and high temperatures. So it's not a job for an impatient person at all. But it is a job that requires teamwork and perseverance.

We can go for months and not find any human ancestral remains. And when you do find a little piece of a hominin, you know it's the very first time anybody's ever seen that particular piece. Joining Louise on today's fossil hunt is Nairobi National Museum's Director General, Mary Gakungu.

I think that's a bit of a tool. You see how it's been worked. Oh, my God, this place is so rich. This is the way we found all those fossils like the turkana boy and things that are in the vault in the museum. What you got? Let's see what you have here.

Wow. So could it be one. One horn? It's beautiful. As we know that we need to make more space in the museum because, as you can see, there's so much fossil out here. And every year we have teams of people looking and finding more fossils. Where are we going to put it all?

I agree with you that there is need for expansion of collection centers, because right now they are overstretched. These collections, many of them you can't find in the wild anymore, they're gone. These may be the only examples of certain things that are left.

The Nairobi National Museum is perhaps best known for its hominin fossils, but it also boasts impressive collections of insects, bones, amphibians, and fish. Whereas the greatest challenge facing the fossils is storage, the insect collection is most threatened by the possibility of fire. entomologist Dino Martens is exploring the backroom of the museum's vast insect collection.

One of the amazing things about these collections is that I can come here and look at them today, specimens that were collected almost 100 years ago, and I can learn from them. I can put them away. And 100 years from today, somebody else can come and look at them and learn something different and move knowledge forward.

And this is why museum natural history collections is so important. All right, sleep nicely. Butterflies. I spend a lot of time at the National Museums of Kenya because it is such an important resource for understanding, in my case, insects.

Scott Miller is a senior research entomologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. Here we go. Preserving museum collections anywhere in the world is a challenge because there are many things that degrade collections over time. In the case of biological specimens, such as we have here, they can be put at risk by a catastrophic event like a fire or a flood.

But they can also be put at risk by much more insidious and sort of harder to observe events, whether that be insect pests eating them or fungus degrading them or light degrading their color and patterns. Catastrophic events at natural history museums are not without precedent.

In 2018, Brazil's National Museum went up in flames, destroying the majority of its 20 million specimens. The Nairobi National Museum's struggles with a lack of resources and funding are a common story for many museums around the world.

In February, Duke University announced it would be closing its herbarium, which is home to a collection of over 800,000 plant specimens. University officials said they could no longer afford to maintain a facility that is one of the largest herbariums in the U.S. in 2000, Princeton University shuttered its natural history museum, replacing it with an environmental institute.

Gikungu is tasked with leading the Nairobi Museum's turnaround.

We are planning to come up with a bigger correction center, whereby in that centre we would have enough space even for more corrections, because in this country, a lot has not been corrected. Kikungu assumed the leadership position last year after her predecessor, Mazalando Kabunja, was charged with allegedly masterminding a scheme to steal $4 million from the museum's coffers by filling its staff with more than 100 ghost workers.

The former National Museum's director general, Mzalendo Kibunja, will spend the night in custody. Kabunja's attorney said that the case against his client is politically motivated. Kabunja pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Corruption concerns have cast a long shadow over the museum, which is why the US was reluctant to give money directly to it. In May, President Biden hosted Kenyan President William William Ruto for a state visit at the White House.

During that visit, the Biden administration announced it would fund an initiative to send Smithsonian experts to Nairobi to assess the museum's needs and plan a roadmap to reform, which would likely include digitizing records and modernizing storage facilities.

Part of the Smithsonian's role is trying to ensure the health and success of cistern museums around the world. Partnering with Smithsonian, the area of digitization, correction management, correction, preservation are some of the areas that we are going to work closely together.

The Smithsonian is expected to begin its assessment in the coming months. Once that is complete, the team of scientists will then need to find the millions of dollars required to save the collection before it's too late.

So there's a lot of investment that needs to go into upgrading the storage of these collections that are important not only for Kenya, not only for Africa, but for the world. They're not housed anywhere else. Kenya insists that these collections be housed in the country in which they were found. And so we need to make sure that we are keeping them safe for the future.

SCIENCE, EDUCATION, GLOBAL, NAIROBI NATIONAL MUSEUM, FOSSILS, PRESERVATION, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL