The video revolves around Michael Connelly, a prolific author and executive producer, who has succeeded in adapting multiple works into series for diverse streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon. Connelly elaborates on the rare achievement of having three concurrent book-to-film adaptations and how the landscape of intellectual property in streaming has shifted, making it more common for books to be the basis of series. He shares insights on whether it was his decision to adapt or a push from Hollywood, his initial hesitance, and how the process evolved with the advent of streaming, leading to successes like 'Bosch' and 'The Lincoln Lawyer'.

The discussion further explores how Connelly navigates the adaptation process, emphasizing the importance of maintaining characters' integrity despite the constraints of screenplay writing, which contrasts with the freedom of novels. He describes his experiences with being involved in casting and creative decisions, collaborating with other writers, and learning to adapt to the art of visual storytelling. Connelly also addresses feedback from audiences regarding his adaptations and the balance between maintaining the novel’s essence and reimagining it for the screen.

Main takeaways from the video:

Please remember to turn on the CC button to view the subtitles.

Key Vocabularies and Common Phrases:

1. prolific [prəˈlɪfɪk] - (adjective) - Producing a large amount of something, particularly in a creative field. - Synonyms: (productive, creative, abundant)

Michael Connelly is a prolific author and an executive producer of three simultaneous book to film adaptations.

2. simultaneous [ˌsaɪməlˈteɪniəs] - (adjective) - Occurring, operating, or done at the same time. - Synonyms: (concurrent, coinciding, contemporary)

Michael Connelly is a prolific author and an executive producer of three simultaneous book to film adaptations.

3. intellectual property [ˌɪntəˈlɛktʃuəl ˈprɒpərti] - (noun) - Creations of the mind, such as inventions, literary and artistic works, designs, symbols, and names used in commerce. - Synonyms: (creations, patents, copyrights)

You know, in Hollywood, IP intellectual property seems to be the ruler of the day.

4. adaptation [ˌædæpˈteɪʃən] - (noun) - The process of changing something to suit a new purpose or situation. - Synonyms: (conversion, transformation, change)

You have three book to film, book to series adaptations.

5. episodic storytelling [ˌɛpɪˈsɒdɪk ˈstɔːrilɪŋ] - (noun) - Narrative told through a series of separate and often loosely connected episodes. - Synonyms: (serial storytelling, chaptered narration, segmented tales)

So that translates well to episodic storytelling.

6. auspicious [ɔːˈspɪʃəs] - (adjective) - Conducive to success; favorable or giving a sign of future success. - Synonyms: (favorable, promising, propitious)

Michael Connelly has an auspicious career, marked by his successful book adaptations.

7. invaluable [ɪnˈvæljuəbl] - (adjective) - Extremely useful or indispensable. - Synonyms: (priceless, crucial, essential)

This involvement proved invaluable to the adaptation process.

8. noble bargain [ˈnoʊbəl ˈbɑːrɡən] - (noun) - A deal or commitment motivated by honorable intentions, often involving personal sacrifice. - Synonyms: (honorable agreement, noble deal, altruistic agreement)

And what I call a noble bargain. I don't think that's changed.

9. ubiquitous [juːˈbɪkwɪtəs] - (adjective) - Present, appearing, or found everywhere. - Synonyms: (omnipresent, widespread, pervasive)

And so now that's ubiquitous in real stories and all fiction.

10. metaphorically [ˌmɛtəˈfɒrɪkli] - (adverb) - In a way that uses metaphor; figuratively speaking. - Synonyms: (figuratively, symbolically, allegorically)

I was always metaphorically putting stuff in my back pocket.

Meet The Author Behind The #1 Show On Netflix - The Lincoln Lawyer - Forbes

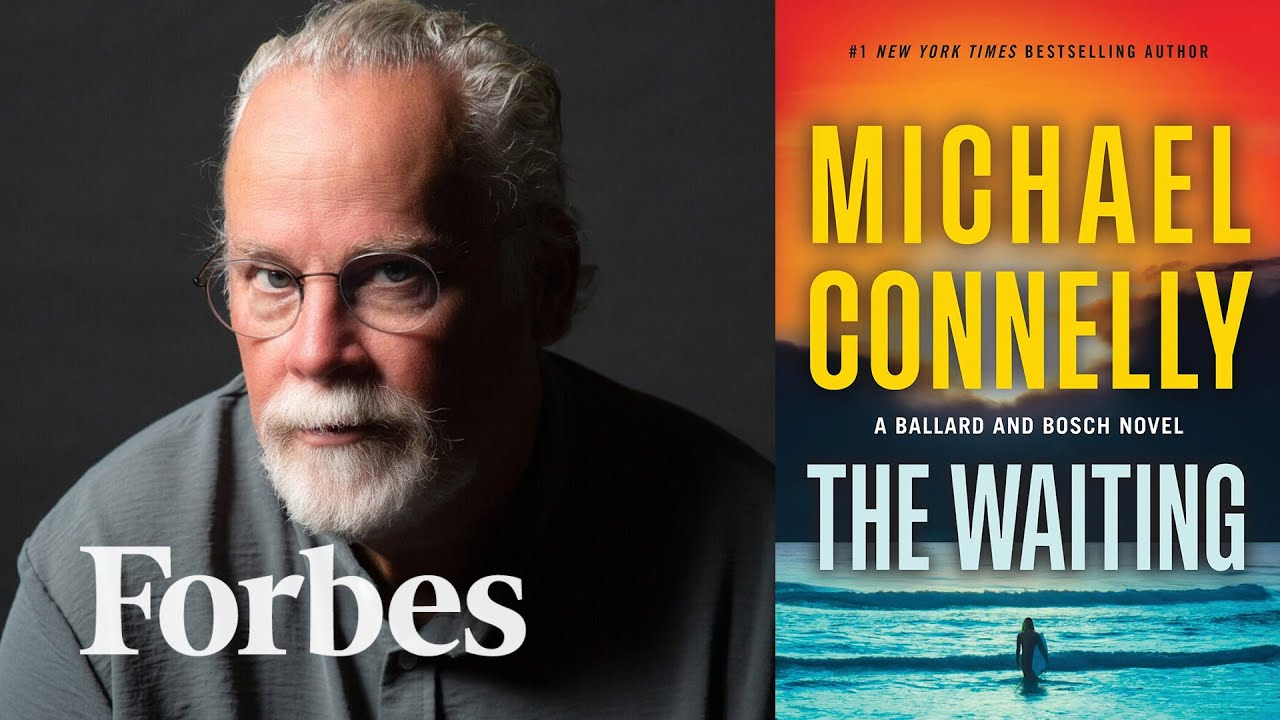

Hi, everyone. I'm Maggie McGrath, senior editor at Forbes. Michael Connelly is a prolific author and an executive producer of three simultaneous book to film adaptations of his the Lincoln Lawyer, Bosch Legacy and the upcoming series following Detective Renee Ballard with his new book the waiting releasing on October 15 and season three of the Lincoln Lawyer arriving on Netflix on October 17. Michael Connelly is captivating audiences across multimedia, and he joins us now. Michael, thanks so much for being here. Glad to be here.

So you have three book to film, book to series adaptations. That's remarkable. Can you put in context how rare that is for an author in the day and age of 2024? Yeah, I can't put it in context. It's really kind of unbelievable that it's, that it's happened and it's not all on the same platform as actually competing platforms. And what's most remarkable to me is that the audience for these books seems to travel. You know, they go where the shows are, and, you know, in Hollywood, Ip intellectual property seems to be the ruler of the day. And that's, that's somewhat new. And, and I think that's what I've been benefited from. IP is the ruler of the day. So is it that audiences are in love with your IP and I in love with your characters and just, they'll go wherever you go? I'd like to say that's all it is, but it's, it's more like it's about money. And I think Hollywood is, is doing less betting on the homegrown things. So if something comes from a book or it comes from a comic, that's where they want to, they feel are safer to invest in that.

So especially on streaming platforms, there seems to be a lot of shows that the origination is a book. Bridgerton comes to mind, and your books especially translate well to film. Or I'm saying film, but I'm using the all encompassing term to talk about streaming because you have many stories, you have a series that follows a character over many years. So that translates well to episodic storytelling. Were you hesitant to enter this medium? Like, take us back to that very first deal? The first time you considered an adaptation, was that something you wanted, or was it an agent or someone else saying, hey, this is a good idea? Well, I have a healthy writer's ego, so I always thought that my stuff would lend itself to a visual form of storytelling. And I had a couple experiences where films were made on my books, but I had literally nothing to do with that. It was more like you get patted on the head and said, and run along and do what you do. Go write a book. We'll take care of this.

And with the advent of streaming 1012 years ago, I think that changed. And so I had a checkered history, I would say, with Hollywood for about 20 years. And then streaming happened, and Amazon came to me and said, more or less came to me and said, let's do this tv show on one condition, that you come with it and you be involved. And that was shocking to me, to tell you the truth. That's not been my, my Hollywood experience. And then a few years, and so then we made Bosch, and it went well. And then the same thing happened with Netflix when they came calling for Lincoln lawyer. They said, we want you there. We want you in the room. Basically, you're talking about the writing room, where it all comes from. It's not like I can be on the set. I don't know anything about camera angles and things like that, but I can. I can be helpful in the room.

In adapting your book into a screenplay, effectively, what's been the most interesting or surprising process of taking a book and turning it into a script? Well, a couple things. One is the, it's kind of bred in you as a novel writer that Hollywood is full of hacks. And if you throw your book over the fence in Hollywood, good luck with it. But I've just been shocked and shocked again at the quality of people involved in adapting these books. The writers, they just, they're just, I trust them completely. And I didn't take a long time to get to that point. I realized that they were not trying to go in a different direction. They were really, the character was sacred to them, and that translated into the process coming from it, from on another angle, coming from. To this world, from being a book writer, where you have immense freedom, where you can go in characters heads and say what they're thinking and what their point of view is. You can't do that in scripts. And so that was a, I have written some of the scripts on these shows, but I have to say I'm rewritten quite a bit because that's a very difficult transition for me to make.

You're rewritten quite a bit. That's for folks who write themselves and are rewritten. That's almost encouraging to hear someone as experienced as you, even in a different environment, is getting rewritten. Yeah, I mean. Cause I would, in my early scripts, I'd say Bosh thinks this and that would get scratched out. How do you film what someone's thinking? You can't. So to me, it's a big, it's almost half of what I do, or at least a third of what I have when I'm writing a book. How I connect to readers is through how Harry Botch thinks or how Renee Bauer thinks. And that goes out the window, and it's all based on what they say and what they do, actions and words. And that is an art in itself. And I got a front seat. I'm in the front row watching that happen with some really talented writers.

It's interesting that you say that because as someone who reads a lot and has conversations with friends about, oh, I don't want to watch this series. Cause I loved the book so much, I heard another author say, well, yeah, the reason you don't like the film adaptations is because you can't use your imagination as much as you do when you're reading, when you're watching something on film. Precisely for the Bosch thinks this, the inner monologue and the details that your own brain fills in the screen is telling it to you. What has been the feedback from your audiences with these adaptations? Well, I have to say I was very aware of that, and I felt a little bit like I betrayed my audience, because take Bosch, for example. I've written millions of words about him, but probably all the descriptions, physical descriptions of him in all the books probably adds up to less than ten pages.

I've always written the way I like to read, which is I like to build a character's everything in my head, and that's what's sacred and wonderful about reading. And so I've done that for like, 20 some years. And then suddenly I'm saying, this is what he looks like. Here's the tv show, and this is what he looks like. So I've had a lot of what you just said. I've had people come up to me at book signings and so forth and say I can't watch the show because I have Harry in my heart and in my head. And no matter how good Titus Welver is, and I think he's fantastic, you know, they're not going to be able to jump that, that chasm and watch the show.

Now, talking about Titus Wellver and the other actors and actresses involved in the series, how involved have you been in picking these people? Because I heard a story, at least with Titus, where you kind of had him in your head. You waited in a meeting to bring up his name. But in general, are you saying, like, this is my dream cast and go forth and get these people, or are you sitting in auditions? Take us through the process. Well, one of the things I have to understand is that I'm a good book writer. Like I said, I have a healthy writer's ego, and that's what I can do. I mean, what do I know about the nuances between great acting and okay acting? You know, I'm not an actor. I haven't had that experience. And so I kind of learned early on that I should not get too deep into auditions and so forth.

But, you know, there's always one character that's the main character that comes right out of my books, and I want to have a say in that. And, yeah, I was the first one who pitched Titus Wellvert. I mean, we had a meeting, and there was, like, five pages of actors names, and his name wasn't on it. And he was in my mind, because I had seen him portray an ex vet who had PTSD, and he didn't have to say, hey, I got PTSD. You could see he was carrying it behind his eyes. And that's what we needed, because I've been briefed that we're not going inside Harry Botch's head, so we got to find someone who can project what he's carrying inside. And so I had seen Titus in a guest role on a tv show where he was this guy with PTSD. Then we come to this big meeting with two casting people, and his name wasn't on the list. So I was very timid.

About what? About Titus Welliver. And then I braced for, like, we can't work with that guy. He's awful, or something like that. And they said, oh, we love him, but he's making a movie in Hong Kong. And we had a very prescribed. I think it was a six week period where we had to find Bosch or delay the project because everything was set. You know, we had stages rented. We had all these things ready to go, so we had to find the guy in six weeks, and we didn't find him. And then on the very last week, they said he was coming back from Hong Kong to see his kids, who he had not seen in a few months because of his filming. And we said, well, that's really important. Family's important. But is there any way we can get him for a couple hours to come and talk to us? And he did, and he got the job in the room.

That's incredible. As you talk about building sets in the production schedules, I'm curious, because we are one year on the other side of writers and actors strike that tremendously disrupted production schedules and Hollywood output. What was your experience with the writers strike, and how did that strike affect the progress on these three series that we're talking about? The strikes were very disruptive. I was on the strike line quite often. I really agreed with what the Writers Guild was trying to accomplish because especially in this world of streaming, it's just most shows are only ten episodes instead of 22. So it's very hard for writers to make a good living because they'll spend seven months making a ten episode show, so there's less pay there. And then they got to try to find something else. There's also lots of delays between approvals of continuing seasons and so forth.

So it's been become streaming has really kind of upset the apple cart, and I agreed with the efforts that were going to be made to make it a little bit more financially attractive to be a writer in Hollywood. So having said all that, it has, the ripple effects of that have been immense, and there's very little production going. Again, I'm happy that since the writers struck that we've done a Lincoln lawyer season, we've done a Bosch legacy season, and now we're seven episodes in the filming of Ballard. And so at least my shows are going forward. But I know from talking to crew members and so forth, there's very little work out there as the, I don't know whether it's because of money lost during the strike, but the studios seem to be constricting and going forward with fewer projects.

I was talking to a producer and director, and she said something similar. And I think another part of the problem is productions are getting shipped overseas or places where it's a little bit cheaper to film. But where do you do the bulk of the filming for your series? So far, everything of my shows have been in LA. And it's, you know, in these books, LA is a character, you know, just as big a character as Harry Bosh. And so I took advantage of, like, when Amazon came to me about twelve years ago and said, we're making our own shows and we want to make Bosch. Well, at that point, they hadn't made any, so it was a bit of a gamble going with them. But I happened to enjoy some lifelong insomniac, and I was an early adapter of streaming stuff, stream it through the night. So when they said, we're going to make a streaming show, I said, I'm all in.

But they also were new at it and they made an agreement that in my contract I said I'd only do this if you film every shot in LA and because LA is a character we're going to make LA a character in the show just like in the books and they agreed to that and I think they later rude the day they agreed to that because they could have shipped a lot of the filming interiors and so forth to Canada where it's cheaper and you get tax credits and things like that but then the other shows just happened to follow suit. I did not have that contractual thing in Lincoln lawyer or in Ballard but we're filming all scenes in LA. One of the few shows that's or companies that is making stuff in LA that's really interesting. And I think if I was reading background on you correctly there's a writer who had a short chapter in one of his books that described LA that was one of your earliest inspirations. Am I getting that right? I'm trying to remember that one.

There's been a lot written about me. It sounds like a true story, but can you give me another hint about it? It was chapter 13, that's what's sticking in my head. Chapter 13 of a book. I thought you meant dealing with Hollywood. Yeah, I mean, no, I think going back just the writing and story, I think. And it's funny, I'm a book writer, but I became a writer because of a movie I saw, the 1973 version of the long Goodbye that Robert Altman directed with Elliott Gould as the classic detective Philip Marlowe. And I saw that movie when I was in college. Then I started reading the books and I stopped going to classes and changed direction. Said, I want to be a writer. At the time I was in an engineering major, but. So, yeah, those books changed my trajectory of my life.

But in one of Chandler's books, the little sister, chapter 13, it's just a very short chapter where he drives around LA has nothing to do with plot. He's frustrated by the plot, he's frustrated by the case he's on he's a private eye and to get some air he drives around LA and describes LA. And I think that book was published in 1939 and the description holds up, you know, things have changed, obviously, but the feeling of LA and the light of LA and everything about it just rings true. So that is an inspiration. I read that chapter over and over in the course of writing a book. Really? So every time you write a book you return to that? Yeah, that's like raising the flag. Okay, it's time to start again. Let's go through it. There are a couple routines I do and one of them is reading that chapter from the little sister.

That's interesting. What are the other routines? I know you have an faq on your website where you talk about the structure of a day, but what is something that people wouldn't expect that you do? Well, I have a. Some kind of weird stuff, but anyway, I drink a lot of iced tea when I'm writing, and so I have kind of, like, what you'd find in a restaurant, a really big brewer that brews two gallons at a time. And I. And I, you know, I get the iced tea going. I think a lot of writers are superstitious, and I am. So my first book I wrote, I didn't really have an office at home. Didn't have room for one, so I wrote it on a couch next to this kind of antiques lamp, and I still had that lamp, and I always want that lamp because that. The first book I wrote, I wrote under that light from that lamp. And so I recreate that as well. So those are the things that are the same. I'm wondering, has anything changed about your writing process, especially since you started adapting your stories for film?

Do you think more in terms of a script or a series flow as you're sketching out the plot line for one of your novels? I try not to. I don't. You know, I don't want to think, like, this is gonna look good on television, but you can. I mean, I have now, like, ten years experience producing television, and so I can't help but not think about that. But, you know, for the most part, you keep your head down. You know, you need visual things, forensics, parts of the city, and things like that. But that's all window dressing on a character story. So that's really. I'm always concentrating on the character story, and I think if I get that right, other things, like television, so forth, will follow.

Your new book, the waiting is officially your 40th book, is that correct? 39th novel. 40th book overall. I did put out a nonfiction collection of my journalism once. 39th book. 39th novel. How do you maintain that level of production? I hate to use the WB word, the writer's block word, but that's a remarkable run. Well, I think I benefited, and this was not part of the plan. It just. It's just the way it is. You know, when you're at a newspaper, you don't have writer's block. You can't ever say, you know, boss, I don't have it today. You got to write. You write every day. And when you're on a crime beat, like I was. And again, remember, I was journalists in the eighties and early nineties, so the newspaper business was fat and happy and returning 20%. You know, it's not like it is now a crumbling industry.

And, you know, so I. It was really thick, newspapers, a lot of space for stories. And I wrote crime in South Florida and then in Los Angeles, places where you didn't go wanting if you were a crime beat reporter. And so I was writing multiple stories a day, and that kind of gave me a work ethic that I carried over into my novels. And, you know, so I write every day. I usually start early and, you know, now with the Hollywood stuff, luckily, Hollywood doesn't get going every day till like, ten or eleven. So, you know, like, most of the writing rooms start at eleven. They go to like eleven to four, and then that's when everyone's in the room. And then you do your own writing of scripts afterwards or before, whenever you want to do. But that's been. I've been able to maintain starting early, usually 630 or seven and writing to ten or eleven. And so I've not had a blip in terms of publishing books while all this tv stuff has been happening.

That's remarkable. But let's talk more about the journalism, because you started as a crime reporter, and I'm wondering, was writing fiction always the goal, or was it somewhere along the crime beat that you realized you wanted to make a switch from nonfiction to fiction? No, the fiction was always the first goal. You know, after I changed from being an engineer major, I talked to my parents and they had the idea of don't switch to english lit. And then you end up being a teacher or whatever. If you're very specific about wanting to write mystery stories and crime stories, you should go back into journalism and get a press pass and get into police stations and talk to real life detectives. And it would hopefully be like research, and hopefully put you in a position to take your shot at writing a crime novel. So I always had that, you know, and so I was always put, you know, metaphorically putting stuff in my back pocket that I knew. This doesn't really belong in a newspaper story, but someday I'll put it into a novel.

That was smart advice from your parents. Yeah. My dad had been a frustrated artist. He had wanted to be a painter. And, you know, we got into the Philadelphia Institute of Art and was. And, you know, there's paint. I grew up with his paintings on the walls of our house and stuff, but he had to put it aside because he was raising a family. And so he had that kind of frustrated artistic aspect of him. So I got to tell you, when I came home from, I drove home from school after having this moment where, like, I don't want to be an engineer. I want to be a writer. And I didn't think I would get a good audience from my parents on that. And instead, it was like, yeah, what you want to do now is a long shot, but how can you get into the best position to take that long shot? That's when my father said, I think you should go into journalism school.

Are there things that even now, today, in 2024, that you draw on from your time as a journalist in the eighties? Absolutely. Every day. I mean, it's so weird. Everything has changed. You know, I was, one of the last stories I wrote about was the first use of DNA in a criminal case in California, you know, and so now that's ubiquitous and all stories and all real stories and all fiction. And, you know, so it's changed a lot. But what hasn't changed is the mission oriented detectives that I knew, people that sacrificed a lot to do what they do and what I call a noble bargain. I don't think that's changed. And I write about people who have made that bargain that are willing to do this kind of work, even though it could cost them in many different ways. And so I saw that a lot when I was on the job. I gravitated towards those people as sources and so forth.

So, yeah, I still, if I didn't have those 14 years or those twelve of the 14 years I was a journalist, I was on the crime beat. If I didn't have those twelve years, we wouldn't be talking. Because it influences all these years later. It influences my books all the time. That's incredible, especially because the nature of crime has evolved, right? There's much more digital crime. How have you grappled with the changing nature of society and the changing nature of crime in your work? To me, it's not a grapple. It's like an opportunity, you know, and things change fast. And so if you can, my books are very contemporary. They're set in the years that they're published. And, you know, and I have connections. I'm not long time, I haven't been a journalist more than 25 years. I think if I do the math, but I still have connections, and I have a cadre of people that help me with my books, and they're learning this stuff.

Most of them are still working in investigative work, and so they're learning this stuff, and they pass it on to me. So to me, it's not something like, oh, I gotta learn how to do this. To me, it's all a great challenge and opportunity to put it in a book and be on the front wave of that in terms of fiction, but also explaining things to readers. Now, your latest book, the waiting, comes out October 15. What can readers expect from this book from Renee Ballard? What can you say without giving too many spoilers? Well, it's the second book I've written where she's running a cold case squad, and Renee Bauer is a single source inspiration. She's based on a real woman who ran LAPD's cold case squad till she retired in April. And so I have this person kind of like sitting on my shoulder as I'm writing these books. I'm constantly asking her, what would you do here? What would you say? What's the next moves?

And so I think that has a built in veneer of accuracy to the books, if you will. And so we're going to see more of that, and we're going to see here dealing with the politics and bureaucracy of being a, you know, a commander of a unit within the LAPD. So you have that aspect that I'm always fascinated with. But also there's, you know, it says on the COVID of the book Bower and Bosch novel, and the question is, which Bosch? Because Harry Bosch is in it, but his daughter really comes forward in a big way in this book, which I have not done before. And so to me, that was the, the through line that really kept me involved and excited about this book is that this is like a bit of a passing of a baton to Mattie Bosch. That sounds really compelling. I look forward to reading it. And then your other release, so to speak, this week, season three, Lincoln lawyer, Netflix. What can you say about that?

Well, it's a great season. We've raised the bar every time, I think so. The third season is the best season, in my opinion, and that might be colored a little bit. It's based on my book called the Gods of Guilt, which happens to be my favorite Lincoln lawyer book. And what we did with it, I mean, it can never just be the book. You got to bring in other characters, give them expanded lives, because my books are usually carried through a main character, and in tv, you just can't do that. You'd kill poor Manuel, would die if he had to be in every scene. So you expand and you give other characters that are ancillary in the books, but you give them fuller lives, and they've done that so well in this show, and it really comes together in the third season. Really? Really. It was a really fun one to be involved in. I know you get asked for advice all the time, so I'm going to frame this in a slightly different way.

Before we started rolling here, you mentioned that you've had the same publisher your whole career, and you've only had two editors in 32 years. What's your advice to aspiring writers or working writers about finding editors and publishers that will be faithful in telling their stories and helping put their stories forward to the world? It's a tough question for me because just like, everything in the world has changed a lot. You know, when I found my first agent and he got my first deal, there wasn't even the Internet. There was no email. I was sending letters and doing phone calls. So it's a little bit different in some ways. There's more opportunity. I mean, there's no self publishing and things like that, you know, digitally and so forth that there is out there now. You know, some. But the one thing that I think is universal and doesn't change over time is that it's all about the story. You know, it's keep your head down and write a story that's going to have a connection to you.

Never, like, lick your finger and hold it up into the win and say, what is John Grisham doing? You can't do that. I think the apparatus of publishing, in some ways is a meritocracy, and they're all looking for a good idea, well executed. And it comes down to character. They're looking for an interesting character they haven't read before. And you can only accomplish that if to keep your head down and focus on something that's coming from inside you. I mean, it can be inspired by a true crime. A lot of my books are inspired by stories I've true stories I've heard from detectives and so forth. But it's really, you know, it's really about you in that space, wherever you're working with the antique light over your shoulder or whatever, you know, keep your head down and write. And then the next aspect of getting representation and so forth, that's an arduous process, but every writer goes through it.

And finally, if we were to speak a year from now, what do you want to be able to tell me about your career, your books or your series? Will there be more? Will there be new characters? Yeah, next year, I'm going to pop out with a new character after the waiting. My next book will be a new character. So hopefully we'll be talking about how that character was received. Well, you know, and as a unique character, my work. So that's been the exciting thing that's happening now. I'm writing about a brand new character, and then by next year, we'll see how he is done. It's a male character. Well, we'll have to have you back to hear how that's going. But in the meantime, Michael Connelly, thank you so much for being here and what is a very busy week for you. Thanks a lot. Thanks for having me.

Entertainment, Literature, Hollywood, Technology, Adaptations, Streaming Platforms, Forbes